When Courts Kill Executive Orders

No president is above the Constitution.

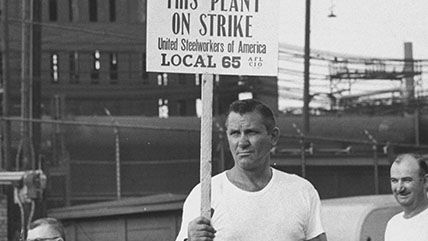

On April 4, 1952, the United Steelworkers of America called for a nationwide strike in the hopes of driving up wages throughout the steel industry. But on the eve of the planned walkout, President Harry Truman stuck his nose where it didn't belong. With the stroke of a pen, Truman killed the strike by ordering Secretary of Commerce Charles Sawyer to seize control of most of the nation's privately owned steel mills and operate them on behalf of the federal government.

How did Truman justify this sweeping exercise of presidential authority? How else? He raised the specter of national security and invoked his "inherent powers" as commander in chief. Pointing to the presence of U.S. forces in Korea, Truman insisted that the success of the war effort depended on the president's unilateral ability to keep the steel mills humming. "In order to assure the continued availability of steel and steel products during the existing emergency," Truman wrote in Executive Order 10340, "it is necessary that the United States take possession of and operate the plants, facilities, and other property of the said companies."

Unsurprisingly, the said companies took a different view of the matter. They filed suit in federal court, charging Truman with usurping the legislative powers of Congress and overstepping his lawful powers as president. A little less than two months later, the Supreme Court stopped Truman dead in his tracks.

"The President's order does not direct that a congressional policy be executed in a manner prescribed by Congress—it directs that a presidential policy be executed in a manner prescribed by the President," wrote Justice Hugo Black in Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company v. Sawyer. Yet "the Founders of this Nation entrusted the lawmaking power to the Congress alone in both good and bad times." To hold otherwise, Black said, would be to turn the Constitution on its head. "It would do no good," he added, "to recall the historical events, the fears of power, and the hopes for freedom that lay behind their choice. Such a review would but confirm our holding that this seizure order cannot stand."

Harry Truman was not the first president to issue a lawless executive order and he quite obviously has not been the last. That's why Youngstown remains such an important precedent to have on the books. Even in times of war and national insecurity, the ruling insists, no president is above the Constitution.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "When Courts Kill Executive Orders."

Show Comments (10)