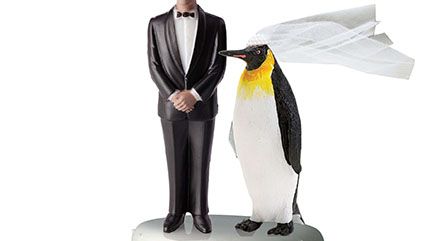

Christians Started the Wedding Wars

Defenders of traditional marriage used the law to persecute polygamists. Now they're the ones under attack.

A man who lived with more than one woman was anathema in the 19th century; the media called polygamy an "act of licentiousness" that deserved to be categorically denounced, its adherents disenfranchised. In 1885, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a federal law making plural marriage a felony, declaring that "the union for life of one man and one woman in the holy estate of matrimony [is] the sure foundation of all that is stable and noble in our civilization." A New York Times editorial celebrated that result, observing cheekily that "we had not supposed there had ever been any serious question."

Today, it's the old-timey view that marriage is between one man and one woman only—and that sex should be reserved to that union—that raises the Grey Lady's ire. When Californians sought to ban gay marriage in 2008, the editors of the Times called the initiative a "mean-spirited" effort "to enshrine bigotry in the state's Constitution."

Even assuming you think the paper was right the second time around, the reversal is striking. But while the norms have clearly changed, the desire to punish anyone who refuses to comply with those norms appears to be forever.

As the nation goes to war over birth control mandates and gay wedding cakes, many religious supporters of traditional marriage and sexual mores understandably feel their rights are being trampled. But so did the Mormons a century ago. To justify the anti-polygamy laws forbidding that group to live out its faith, Christian traditionalists stretched the First Amendment to precarious lengths. Now, the arguments they created and employed are being turned against them.

Discrimination Nation

"We can't promote a marriage that God says isn't really marriage," the blog post would have read. "Even if our beliefs are a bit different or unpopular, we have to stick to them."

But those words, penned by Joanna Duka and Breanna Koski, were never published to their website. The authors feared the government of Phoenix might come after them if they were.

The young women, aged 23 and 24 respectively, are the owners of Brush & Nib Studio, an Arizona-based custom artwork and calligraphy shop. Shortly after getting their new business off the ground in 2015, they realized that a city ordinance passed two years earlier opened them up to enormous fines and even jail time as a result of their beliefs. The law forbids certain companies not just from discriminating against gays and lesbians but also from saying anything that so much as implies a customer would be unwelcome because of his or her sexual orientation.

Duka and Koski don't want to be forced to create wedding invitations and other artwork that celebrate same-sex marriage, so they're suing to overturn the Phoenix regulation as a violation of their First Amendment rights. Their prospects seem grim, however: In September of last year, the Maricopa County Superior Court denied their request for a temporary injunction to stop the law from being enforced while the challenge proceeds. "There is nothing about custom wedding invitations made for same-sex couples that is expressive," the decision, incredibly, reads.

That ruling is just one in a litany of recent instances in which small business owners have faced serious legal consequences for not wanting to be involved in commemorating same-sex unions. In Colorado, the owner of Masterpiece Cakeshop was hauled before the state's Civil Rights Commission. In Oregon, the proprietors of Sweet Cakes by Melissa were fined an eye-popping $135,000 and had to shutter their storefront. In New Mexico, the state Supreme Court told photographer Elaine Huguenin that she and her husband would be "compelled by law to compromise the very religious beliefs that inspire their lives." In upstate New York, a couple was forced to stop renting out their farm for wedding ceremonies unless they agreed to let gay couples marry there as well.

In theory, the Constitution is supposed to prevent things like this. The First Amendment says that the government "shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof." In each of the above cases, though, the government got around that limitation by arguing that individuals have the right to believe as they like on their own time, but when they venture out into the marketplace, they forfeit the privilege of acting in accordance with the dictates of their faith.

The same supposed distinction between private opinions and public behaviors also features prominently in debates over the Obama administration's contraception mandate.

That rule, which was handed down by the federal Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in 2012 as part of the Affordable Care Act, said that free birth control coverage had to be included in all employee health insurance packages. But some religiously affiliated employers, and in particular Roman Catholic ones, believe that facilitating the use of contraception makes one complicit in sin.

The agency exempted houses of worship from the rule, which let Catholic churches off the hook. But that did nothing for Catholic schools, hospitals, nursing homes, adoption agencies, and other charities. Eventually, the administration offered an "accommodation" in which the groups' insurers, rather than the groups themselves, would technically be responsible for paying for the coverage. Not surprisingly, this accounting sleight of hand did not allay the charities' concerns.

In Zubik v. Burwell, a coalition of faith-based nonprofits asked the Supreme Court to determine whether the mandate, as applied to such organizations, violated their religious freedom. Among the petitioners are the Little Sisters of the Poor, an order of Catholic nuns who care for the indigent elderly and have become the public face of this dispute.

Despite the nuns' sympathetic character, the political left remains strongly opposed to allowing them and their coreligionists to opt out of the requirement. "What these people are after isn't religious freedom," wrote Barry W. Lynn, executive director of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, in a blog post that represents the general tenor of progressive rhetoric on the matter. "It's the right to use theology to control the private behavior of others, to impose their religion on the unwilling and to employ narrow dogma as an instrument of discrimination."

Discrimination is a term that comes up frequently in these debates, since "the very nature of religion is 'discriminatory,'" says U.S. Civil Rights Commissioner Peter Kirsanow. "Now, it's not invidious discrimination. But Catholics are different from Jews. And Jews are different from Muslims. And Muslims are different from Protestants, and on and on."

Kirsanow argues that those differences ought to be respected. "One of my main concerns is the elevation of principles of nondiscrimination over principles of liberty," he says. "We should be more concerned about government coercion than we are about individual coercion. Both may be bad, but one is scores of orders of magnitude more serious than the other. And one was the principal reason we fought a revolution."

Yet in case after case, the desire to prevent business owners from taking steps that inconvenience someone else—either by forcing a customer to drive a few miles to a different pharmacy or wedding vendor, or by requiring an employee to sign up for a separate insurance plan that covers contraceptives—is treated as the ultimate consideration. Religious liberty, at least as far as it informs a believer's actions and not just her opinions, is treated as subordinate.

America vs. the Mormons

The idea that the Constitution protects only what happens between a person's ears isn't novel. It has roots in a series of laws, and the Supreme Court decisions that upheld them, from 1862 through 1890. The goal at the time was to rein in a new and dangerous-seeming religious movement called Mormonism by criminalizing its most eccentric practice: polygamy. But by claiming the right to regulate the behavior of people of faith, mainstream believers set the stage for the modern political left to step in and regulate them—and to have 150 years' worth of precedents on their side when they did it.

The Mormon faith, today known as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS), was founded in 1830 by a farmer named Joseph Smith. As the nascent religion picked up followers, it attracted an increasingly violent resistance from the non-Mormon "gentile" community, eventually culminating in an all-out legal assault against the early Church.

Smith and his followers were repeatedly driven westward—forced from their encampments in Kirtland, Ohio; Jackson County, Missouri; and Nauvoo, Illinois, before settling in the Great Basin region of what is now Utah. They were harassed wherever they went, often with the approval of local officials. On one occasion Smith was tarred and feathered. Years later he was murdered by a mob that broke into the Illinois jail cell where he was being held. Even after the Mormons settled along the Great Salt Lake, they were still hounded by government authorities. In the 1850s, President James Buchanan sent forces to Utah in what the people there viewed as a military invasion. Relations between the federal troops, the Latter-day Saints, and the fortune seekers streaming west to partake in the Gold Rush remained tense for decades.

There were a number of reasons for Americans' deep hostility toward the Mormons, from fears they were amassing too much political power (they tended to vote as a bloc) to the perception that they were zealots bent on establishing a theocratic government on American soil. "I think they were unwise in some of the statements they made to the locals," says the Brigham Young University historian Brian Cannon.

But the emblem of the alleged Mormon threat was polygamy, a practice Smith introduced to his inner circle in Nauvoo shortly before he was killed.

In 1852, the LDS Church began openly defending plural marriage. This is what elevated the "Mormon problem" to the national stage. Beginning in the 1850s, Eastern newspapers were rife with references to polygamy as "evil," "licentious," a "brutalizing practice," "repugnant to our sentiments of morality and social order," and "shocking to the moral sense of the world." The New York Times editorialized repeatedly for taking direct action against the Latter-day Saints. "The fact, if it be a fact, that the women are willing to live in polygamy, is no reason for our allowing them to do so," the editors of the paper wrote in March 1860. What had begun as rival groups skirmishing over frontier resources came to be seen as an existential conflict: The soul of the whole country seemed to be at stake if the federal government allowed such behavior to continue.

Plural Marriage 'Extirpated'

Plural marriage was tied up with slavery in the politics of the day. The GOP platform in 1856 famously called upon Congress "to prohibit in the territories those twin relics of barbarism, polygamy and slavery." But not everyone agreed—with the second half of the Republicans' prescription.

In 1853, a "Southern contributor" to one of New York City's daily newspapers published a lecture arguing that of the two, polygamy was actually the worse offense. (At least slavery, he said, was tolerated in the early Christian faith.) Arguably one reason a prohibition on plural marriage wasn't passed sooner was a fear among some Democrats that abolition might follow. North Carolina Rep. Lawrence O'Bryan Branch said he could not support a federal ban because "if polygamy was declared criminal, there would be no reason why the same action might not be taken regarding slavery."

Even so, they made their feelings about the Mormon practice clear. "The knife must be applied to this pestiferous disgusting cancer which is gnawing into the very vitals of the body politic," thundered presidential hopeful Stephen Douglas in 1857. "It must be cut out by the roots and seared over by the red hot iron of stern and unflinching law."

The Civil War eventually put an end to the prohibitionists' need to allay Southern concerns about federalism, and in July 1862 the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act became law. "That the purpose of the bill is entirely right and commends itself to every true friend of morality and civilization," wrote the editors of the Times, "will scarcely be questioned anywhere outside the circles of Mormondom."

At first it meant little. Since most everyone in Utah territory was Mormon, attempts to enforce the ban turned out to be virtually impossible. How do you prove a man has taken multiple wives if no one will testify against him? With the judges and juries populated by polygamists and their neighbors, the Morrill Act was effectively a dead letter.

Lawmakers in Washington and the good, upstanding Christians they represented were not about to roll over and accept polygamy, though—even 2,000 miles away. Agitation began for legislation to increase the penalties against those who condoned plural marriage.

By the early 1880s, the Rev. Dr. John Philip Newman, a bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, was giving sermons in which he "pleaded in behalf of women, God's last, best gift to man, that the curse should be wiped out." He didn't mince words: Since "the people of Utah are clothed with the rights of citizenship, and have their courts," he said, "the courts must therefore be overthrown by a military invasion."

The government didn't quite go to war. But it took to arresting those it found to be living with multiple women, even if it couldn't show they were married. According to law professor Ray Jay Davis in the Encyclopedia of Mormonism, more than 1,300 Mormons were jailed as "cohabs" during the 1880s.

Prosecutors even tried to argue they could re-arrest cohabs as they left prison—after all, residing with more than one wife was a "continuing offense." But "in a rare win for the Mormons, the courts ruled that officials had to find new evidence of violations of the law before arresting someone who had already done time," says Kenneth L. Cannon, an attorney whose great-great-grandfather, the Mormon leader George Q. Cannon, was convicted of unlawful cohabitation in 1888.

In December 1881, Sen. George F. Edmunds of Vermont introduced a law to make anyone who accepted the Church's teachings on polygamy ineligible to vote, hold public office, or serve on a jury. Again, the editors of the Times endorsed the act's passage: "It must be admitted that the Edmunds bill is a harsh remedy for polygamy. But then the disease in Utah has gone beyond remedies that are not more or less heroic."

It passed, as did another law five years later disincorporating the Church and declaring that all Church property and assets above $50,000 would be confiscated by the government.

The efforts worked—but only "after four years of harsh and in some cases ruthless enforcement, and only after thousands of lives had been ruined," according to a 1987 article in The John Whitmer Historical Association Journal.

On October 6, 1890, LDS President Wilford Woodruff published a manifesto reversing the institution's position on polygamy: "I now publicly declare that my advice to the Latter-day Saints is to refrain from contracting any marriage forbidden by the law of the land."

"It is not coincidental that Woodruff proclaimed the official end of plural marriage" mere months after the Supreme Court upheld the seizure of the Church's assets, George Q.'s great-great-grandson Cannon says. The day after penning the letter, Woodruff wrote in his journal that he was motivated by a desperate pragmatism: "I am under the necessity of acting for the temporal salvation of the Church."

Free to Believe but Not to Act

The Manifesto of 1890 was a landmark victory for the traditionalist view that, as Pope Leo XIII had put it a decade earlier, "marriage, from its institution, should exist between two only, that is, between one man and one woman." But it came at the expense of important constitutional limits on the state's power.

Proponents of the laws barring polygamy were no doubt aware that the First Amendment was implicated. Yet they tended to dismiss these concerns. When pressed on the issue, the New York Democrat Hyrum Waldridge likely summed up the feelings of many supporters of the ban: "I do not propose to say whether it is constitutional or not—I am viewing this as a great moral question."

The laws outlawing plural marriage and then ratcheting up the punishments didn't go without legal challenge. In 1875 George Reynolds, secretary to Church President Brigham Young, agreed to be prosecuted for bigamy as a means of forcing the Supreme Court to consider whether the Morrill Act violated the Constitution. Convicted of having two wives and sentenced to two years' hard labor, he appealed on the following grounds: that he was a member of the LDS Church; "that it was the duty of male members of said church, circumstances permitting, to practise polygamy"; that the punishment for refusing "would be damnation in the life to come"; and that, since his behavior was "in conformity with what he believed at the time to be a religious duty," he should not have been found guilty.

The justices were not persuaded. They acknowledged that "Congress cannot pass a law…which shall prohibit the free exercise of religion." Nonetheless, they held that the conviction in Reynolds v. United States would stand, and they got there by declaring that only the right to believe, and not the right to act on your beliefs, is protected by the Constitution.

"While [laws] cannot interfere with mere religious belief and opinions, they may with practices," Chief Justice Morrison Waite wrote in 1878 for a unanimous court. After all, "if a wife religiously believed it was her duty to burn herself upon the funeral pile of her dead husband; would it be beyond the power of the civil government to prevent her carrying her belief into practice?…To permit this would be to make the professed doctrines of religious belief superior to the law of the land."

The decision should have been suspect from the beginning. It turned on the distinction between beliefs and behaviors, even as it quoted the constitutional prohibition on laws that impinge religious exercise—an active word if ever there was one.

Twelve years later the Mormons filed another objection, this time to Edmunds' law disqualifying them from voting, holding public office, or serving on a jury. Again the Court rejected the challenge. Again the ruling was unanimous.

"It was never intended that the first Article of Amendment to the Constitution…should be a protection against legislation for the punishment of acts inimical to the peace, good order, and morals of society," wrote Justice Stephen J. Field in Davis v. Beason. "However free the exercise of religion may be, it must be subordinate to the criminal laws of the country."

To justify a prohibition against polygamy, the Court had taken the teeth out of the First Amendment.

What traditionalist supporters of the bans did not know at the time was that they had set a precedent with Reynolds and Davis that would later be turned against them. Today, a century after they succeeded in "extirpating" the "evil" of polygamy, it's those who believe in marriage as an institution between one man and one woman only who are left to appeal to the importance of free exercise. Meanwhile, their secular opponents argue that the Constitution protects beliefs but not practices—and certainly not institutional practices.

A Balancing Test Upended

The tables didn't turn all at once, and there have been some wins for religious liberty in the last hundred years. For a time, the Supreme Court used a balancing test to limit the government's power to regulate religion.

In the 1972 case Wisconsin v. Yoder, the Court declared that the Amish could not be punished for taking their children out of school after eighth grade. The requirement "affirmatively compels them, under threat of criminal sanction, to perform acts undeniably at odds with fundamental tenets of their religious beliefs," the Court said. And granting an exception would not cause "harm to the physical or mental health of the child or to the public safety, peace, order, or welfare."

Note that the justices didn't find that the law automatically succeeded because it was a regulation of behavior. Nor did they find that it automatically failed because it was an infringement on someone's First Amendment rights. Instead, they weighed the government's interest in enforcing the schooling requirement against the burden it placed on the petitioners' religious freedom.

The idea that there should be a balancing test had been introduced in Sherbert v. Verner in 1963, when the Supreme Court held that South Carolina could not withhold unemployment benefits from a member of the Seventh-day Adventist Church who found herself without work because of her religion's proscription on laboring on Saturdays. Her religious liberty was found to outweigh the government's interests.

Making restrictions on religious liberty subject to a stringent balancing test (that is, subjecting them to "strict scrutiny") might seem like it opens the door to much friendlier rulings for people of faith. But a 1992 article in the Virginia Law Review found that in fact, the courts rarely sided with people seeking exemptions on religious grounds. Of the 97 free exercise claims brought in the federal courts of appeals from 1980 to 1990, 85 were rejected. "For some courts, the mere fact that a law or regulation existed sufficed to demonstrate a compelling state interest," the author wrote. A George Washington Law Review article that same year described the balancing test as "strict in theory, but ever-so-gentle in fact."

Then in 1990 came the knockout punch to defenders of religious freedom. Adding insult to injury, the ruling was handed down by a conservative folk hero—Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia.

The recently departed jurist is today remembered as a champion of the rights of believers. During oral arguments in Obergefell v. Hodges, the case that legalized same-sex marriage throughout the country, Scalia voiced his apprehension about what he and his colleagues were being asked to do: "I'm concerned about the wisdom of this Court imposing through the Constitution a requirement of action which is unpalatable to many of our citizens for religious reasons."

But 25 years earlier, in Employment Division v. Smith, Scalia wrote a decision that dramatically curtailed Americans' ability to make free exercise claims. In that case, two members of the Native American Church sought an exception to an Oregon statute prohibiting the use of the hallucinogen peyote. Federal law said the substance could be used in bona fide religious ceremonies, but the state law contained no such caveat.

Though Scalia acknowledged that the Church members' use of the drug was religiously motivated, he concluded that the ban was not: It applied to all Oregonians, not just adherents of one particular faith. "The right of free exercise does not relieve an individual of the obligation to comply with a valid and neutral law of general applicability," he wrote. Thus, Oregon was under no obligation to allow peyote use, even for religious reasons.

Scalia made it clear his reasoning was grounded in the Supreme Court decisions that had validated the bans on polygamy 100 years earlier. "The rule to which we have adhered ever since Reynolds," he wrote—the rule, that is, that gives the state maximum berth to regulate people's behavior, including religious behavior—"plainly controls."

This time, the public was aghast. The Los Angeles Times described Smith as "strip[ping] religious believers whose practices violate certain general laws of the[ir] constitutional protection." The Washington Post accused Scalia of having read the "protection of individual conscience" out of the First Amendment. A spokesman for the American Civil Liberties Union called the ruling "terrible" and "an end run around" the country's longstanding commitment to religious freedom. And at a hearing on the matter, Rep. Stephen J. Solarz—a New York Democrat—said the justices had "virtually removed religious freedom from the Bill of Rights."

Americans of all stripes suddenly realized the Constitution would not be enough to shield against laws that interfered with the practice of faith, assuming the laws were "generally applicable." What if the authorities decided to go after a Catholic church for serving Communion wine in a dry county? Or an Orthodox rabbi for "discriminating" by only solemnizing marriages between Jews?

"The ruling galvanized virtually the entire American religious landscape, in part because every faith can envision itself as a vulnerable minority in some situation," the University of Oklahoma political scientist Allen Hertzke wrote.

"To many groups concerned with religious liberty, the case was an alarm bell," Peter Steinfels explained in The New York Times. The Court "was petitioned to reconsider its decision by an improbable alliance" that included everyone from civil libertarian groups to the Traditional Values Coalition.

Some 55 constitutional scholars signed on to the letter, but the justices refused to give the case another hearing. Because of Smith, the government no longer needed to show it had a "compelling interest" when it came to laws that incidentally burdened someone's religion.

Exactly 100 years after the Mormons were bullied into giving up polygamy, those legal precedents had come home to roost.

Freedom Fights Back

Recognizing that the Smith ruling could prove dangerous not just for small minorities like Native Americans and Mormons but for mainstream believers as well, activists, scholars, and legislators sprang into action. Their solution was to pass a law, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), that would re-instate the Sherbert balancing test.

Even The New York Times endorsed the idea. Whereas in Smith the Court "threw away decades of precedent and watered down the religious liberty of all Americans," it editorialized, this law "reasserts a broadly accepted American concept of giving wide latitude to religious practices that many might regard as odd or unconventional."

In November 1993, RFRA passed by the lopsided margin of 97–3 in the Senate and by a unanimous voice vote in the House. Over 30 states would eventually follow suit, ensuring that both the federal government and most state governments would have to meet a high bar before they could burden religious liberty.

"Usually the signing of legislation by a president is a ministerial act, often a quiet ending to a turbulent legislative process," then–President Bill Clinton said upon inking the bill into law. "Today this event assumes a more majestic quality because of our ability together to affirm the historic role that people of faith have played in the history of this country and the constitutional protections those who profess and express their faith have always demanded and cherished."

The Smith decision's smothering of the First Amendment had seemingly been forestalled. And indeed, a 2014 study by Robert Martin and Roger Finke found that in the post-Smith, pre-RFRA period (1990–1993), just 28 percent of free exercise legal challenges had been successful. In the four years following the act's passage (1993–1997), the success rate jumped to 45 percent.

In 2014, the foresight that caused people of faith to support RFRA paid off when the Hahn and Green families (owners, respectively, of Conestoga Wood Specialties, a cabinet-making company, and Hobby Lobby, a chain of craft stores) brought a suit against the federal government. The families objected to the HHS rule requiring employers to provide coverage to their workers for abortifacient drugs.

The Supreme Court, looking to RFRA, sided with the petitioners. "A Government action that imposes a substantial burden on religious exercise," wrote Justice Samuel Alito for the majority, has to "constitute the least restrictive means of serving that interest, and the mandate plainly fails that test."

Justice was restored—except that now, many of the same groups who had praised RFRA's passage in the '90s had come to see things differently. No longer was religious freedom "the most precious of all American liberties," as Bill Clinton had said in his signing statement. Clinton's wife, gearing up for her second presidential campaign, now blasted the Hobby Lobby decision as "deeply disturbing."

The next year, Indiana, which did not yet have a state-level RFRA on its books, moved to enact one. The reaction was explosive. Hillary Clinton tweeted that it was "sad" such a law could "happen today," while TV and radio personality Larry King described it as "absurd," "insulting," and "anti-gay." Major corporations, including Nike, Apple, and Marriott, condemned the proposal. The National Collegiate Athletic Association, headquartered in Indianapolis, threatened to leave the state if the statute passed. Public opinion had once again turned.

Beliefs vs. Conduct

Time and again, liberal activists return to one idea in today's religious liberty controversies: that the First Amendment protects your right to believe whatever you want, but not your right to act on those beliefs. The monster legal precedent that Chief Justice Waite forced into being in Reynolds slipped its cage and found a home on the political left. And like so many invasive species, it strangled much of what predated it, including the previously widespread notion that religious liberty is and should remain America's first freedom.

In September 2016, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights released a report asserting that "ensuring nondiscrimination" is of "preeminent importance in American jurisprudence," and should be privileged, even when it conflicts with free exercise claims. After all, the report suggested, "a doctrine that distinguishes between beliefs (which should be protected) and conduct (which should conform to the law) is fairer and easier to apply."

That idea is the (sometimes explicit) rationale for going after wedding vendors who don't want to participate in same-sex commitment celebrations. As recently as November 2016, when Barronelle Stutzman went before the Washington Supreme Court to challenge a fine for declining to make custom floral arrangements for a gay wedding, the refrain reared its head.

Asked by the court how he would respond to the florist's objections, state Attorney General Bob Ferguson replied: "There is a difference, your honor, between the freedom to believe and a freedom to act. Ms. Stutzman is free to believe what she wishes. But when she…avails herself of the protections and the benefits that come with being a business, there are of course responsibilities that flow from that."

Discussing an attempt by Sen. Mike Lee (R–Utah) to stop states from forcing people to work gay weddings against their will, Washington Post columnist Joe Davidson dismissed the Mormon senator's concerns because, he said, "at question is offensive action, not a belief."

It's the same idea that undergirds the federal government's assault on the Little Sisters of the Poor and countless other religious nonprofits. And it's the same justification Washington invoked in 2007 when it required even privately owned pharmacies to stock and dispense the morning-after pill. Under the rule, pharmacists with conscience-based objections are forbidden from referring customers to another nearby store to fill such prescriptions—they're required to do it themselves.

In 2012, the American Pharmacists Association and more than 30 similar groups submitted an amicus brief to the Supreme Court expressing deep concerns about the regulation. "Pharmacies have long enjoyed nearly unfettered control over stocking decisions," the document read. "Indeed, the ability of health professionals to opt out of services they find personally objectionable is an important component of the health care system."

It didn't matter. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit upheld the requirement on the grounds that, like the Oregon peyote ban, it is "both neutral and generally applicable," and the Supreme Court declined the pharmacy associations' pleas to reconsider the decision.

A century ago, the notion that sex and marriage ought to be expanded beyond their traditional confines was considered depraved, and the use of force was considered justified to stop it. Ironically, the same is now true for old-fashioned beliefs about marriage and sex.

The lesson in all this could not be more clear: When a group uses the law to enforce its particular version of morality on others, it sets precedents that may in time be turned against it. The lawmakers (and their constituents) who voted to punish polygamists in the 1800s had every reason to believe they would remain in the political majority. It would have been unthinkable at the time that the Supreme Court might one day rule nontraditional marriage unions a fundamental right. Yet on June 26, 2015, Obergefell did just that.

Christian traditionalists today, instead of being the propagators of moral norms, increasingly find themselves painted as on the "wrong side of history": opposed to marriage equality, favoring discrimination, supporting policies that are anti-woman. A hundred and fifty years after the Morrill Act, they're finally discovering just how important it is to have a legal system that tolerates dissent and carves out space for lifestyle choices beyond the cultural mainstream. Because suddenly, they are the dissenters.

But there's a cautionary tale here for the political left as well. Loose talk about the "right" and "wrong" sides of history suggests progressives are busily making the same error mainstream Christians did in the second half of the 19th century: assuming the moral forces that are ascendant now will continue to be.

As modern supporters of traditional marriage can tell them, social values aren't set in amber. There's no telling whose beliefs will carry the day down the line.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Christians Started the Wedding Wars."

Show Comments (164)