Relax: Gutting the EPA Won't Make Your Air Dirtier and Water More Polluted

There have been diminishing returns to federal pollution regulation for a long time

President Donald Trump's proposed cuts in the Environmental Protection Agency's budget "will not 'Make America Great Again', " asserted Conrad Schneider, the advocacy director at Clean Air Task Force activist group. "It will 'Make America Gag Again.'" Schneider and other alarmed activists are conjuring the bad old days of the mid-20th century when America's cities were blanketed with smog and its streams clotted with filth. In his new budget blueprint, Trump wants to cut back Environmental Protection Agency funding by 31 percent and fire 3,200 of agency's bureaucrats.

But would such steep EPA budget cuts really unleash polluters to pump out more smoke and sewage? To get a handle on this question, let's take an amble down memory lane to assess the evolution of pollution trends in the United States since President Richard Nixon cobbled together the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970.

First, with regard to air pollution, air pollution in most American cities had been declining over the course of the 20th century. Why? Many American cities had recognized the problem of air pollution in the late 19th century. Consequently they passed ordinances that aimed to abate and control the clouds of smoke emitted from burning coal in industry, heating, and cooking. For example, Chicago and Cincinnati adopted smoke abatement ordinances in 1881.

American Enterprise Institute scholars Joel Schwartz and Steven Hayward document in their 2007 book, Air Quality in America, that emissions of smoke, soot, ozone and sulfur dioxide had been falling for decades before the creation the EPA and the adoption of the Clean Air Act. For example, ambient sulfur dioxide had fallen by 58 percent in New York City during the seven years preceding the adoption of the Clean Air Act. "Air quality has indeed improved since the 1970 passage of the" Clean Air Act, they claim. "But it was improving at about the same pace for decades before the act was passed, and without the unnecessary collateral damage caused by our modern regulatory system."

They attribute a lot of the pre-EPA improvement in air quality to market-driven technological progress and increases in wealth that enabled households to switch from coal to cleaner natural gas for heating and cooking; railroads to replace coal-fired locomotives with diesels; more efficient industrial combustion that reduced the emissions of particulates; and improvements in the electrical grid that allowed power plants to be situated closer to coal mines and further from cities.

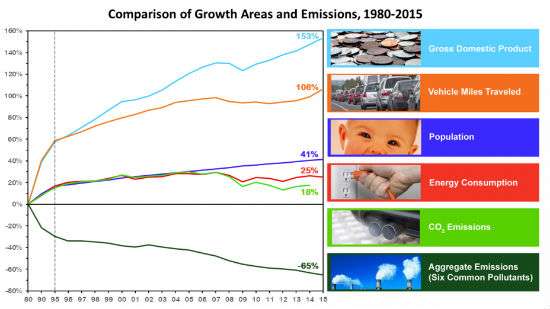

Even if the Clean Air Act did not noticeably speed up the rate of air pollution abatement, the air is nevertheless much cleaner than it used to be. How clean? Since 1980 the index for six major pollutants, carbon monoxide, ozone, particulates, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide and lead has dropped by 65 percent since 1980. In the meantime, the economy grew more than 150 percent, vehicle miles increased by more 100 percent, population grew by more than 40 percent and energy consumption rose by 25 percent. And yet, a 2016 Gallup poll found that 43 percent of Americans say that they worry about air pollution a great deal.

Schwartz and Hayward persuasively argue, "The public's interest lies in sufficiently clean air, achieved at the lowest possible cost. But federal air quality regulation suffers from incentives to create requirements that are unnecessarily stringent, intrusive, bureaucratic, and costly." Basically, the costs of ever tightening federal air pollution controls are now exceeding their benefits. Since most remaining air pollution (except for greenhouse gases which we will set aside for a discussion at another time) is now concentrated in discrete regions rather than crossing jurisdictional lines, cities, counties and states can be reasonably expected to monitor and regulate those pollutants without much federal oversight.

The EPA also regulates water pollution under the Clean Water Act of 1972. That act prohibits anybody from discharging "pollutants" through a "point source" into a "water of the United States" unless they have a permit issued by the EPA that specifies limits on what may be discharged and sets up monitoring and reporting requirements. In addition, the Clean Water Act requires that each state develop a list of impaired surface waters including rivers, lakes, and estuaries. The states also set limits on the maximum amount of each pollutant that can be present in a body of water called Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs).

The EPA under the Obama administration issued regulations that more broadly defined the waters of the United States to include farm ponds, irrigation ditches, intermittent streams, and prairie potholes. At least 32 states had filed lawsuits seeking to block the implementation of Obama administration's new waters of the United States regulations. In February, President Trump signed an executive order instructing the EPA to begin the process of revising the regulations in line with former Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia's plurality opinion in the 2006 Rapanos vs. United States case that would limit EPA regulation of ephemeral and minor sources of water.

Regulation of non-point source water pollution in the form of runoff from agricultural fields and stormwater drainage from city streets is largely accomplished through setting TMDLs by the states. In many ways, this is just the sort of "cooperative federalism" policy that new EPA administrator Scott Pruitt says he intends to pursue. In the past EPA has provided categorical grants to state environmental agencies to help them devise water quality standards and set up scientific monitoring. The new Trump budget cuts such categorical grants to states and localities by 45 percent, falling from $1.1 billion to $597 million. Since the budget document is basically a hortatory wish list, it is not clear to what the claim that "this funding level eliminates or substantially reduces Federal investment in State environmental activities that go beyond EPA's statutory requirements" is referring. Presumably states and localities would be expected to pay more for their own standard-setting and monitoring.

According to most recent water quality data reported by the states to EPA, about 55 percent of the 1,124,000 miles of rivers and streams assessed are considered impaired due to the presence of pollutants like pathogens, excessive sediments, nutrients, and oxygen depletion. Nearly 72 percent of the assessed 18.3 million acres of lakes, reservoirs, and ponds are impaired and nearly 49 percent of the 1.7 million square miles of the assessed estuaries and bays are impaired. The National River and Streams Assessment 2008/2009 reported that 28 percent of the nation's river and stream length is in good biological condition, 25 percent in fair condition, and 46 percent in poor condition. A U.S. Geological Survey report that assessed nitrogen fertilizer runoff trends in the Mississippi River watershed found that they generally increased between 1980 and 2010. Excess nitrogen fertilizer can cause algal blooms that deplete streams, lakes, and estuaries of oxygen producing dead zones.

The sources of water pollutants are always local, but by flowing downstream they become someone else's problem as they cross state, county, and municipal boundaries. Just last week, a federal judge dismissed a lawsuit filed by Des Moines Water Works against three upstream drainage districts in three northwest Iowa counties. The Water Works utility that supplies drinking water to 500,000 Iowans claimed that the drainage districts were responsible for loading up the Raccoon River with nitrate runoff from farmers' fields in their counties. The utility was seeking $80 million to upgrade its nitrate removal equipment from the drainage districts.

A fascinating study just published in January by Iowa State University economist David Keiser and Yale University economist David Shapiro seeks to evaluate the benefits and the costs of the Clean Water Act. Specifically, did the benefits of the 35,000 federal government grants amounting to nearly $1 trillion (2014 real dollars) given to municipalities to improve wastewater treatment plants exceed their costs? To get at this question, the researchers compiled what they claim to be the most comprehensive database on U.S. water pollution trends ever. They find that pollution measures like dissolved oxygen deficits, the share of waters that are not fishable or swimmable, the presence of fecal coliform bacteria, and the amount of sediments in streams had all been improving since 1962 and then flattened out after 1990. Overall they find that during the "period 1972- 2001, the share of waters that are not fishable and the share not swimmable each fell by 11 percentage points."

They do, however, note that "the rate of decrease in pollution slowed after 1972" when the Clean Water Act was adopted. For example, oxygen levels in streams and lakes were improving at a rate of 3 percent per year before 1972 and fell to 1.5 percent thereafter. They suggest that the slow-down could have resulted from the fact that lots of relatively cheap water pollution abatement had been implemented before 1972 and/or that increases in harder to regulate non-point source pollution counterbalanced the improvements achieved through better wastewater treatment.

Keiser and Shapiro try to get a handle on the benefits of the $1 trillion in federal grants spent on wastewater treatment plants by parsing the trends in housing values up to 25 miles downstream. Without going into the details, they calculate based on housing values that the costs of the Clean Water Act wastewater treatment grants were about three times greater than their benefits. They suspect that people value water pollution abatement considerably less than they do reductions in air pollution due to differences in the health consequences of breathing unfiltered air versus drinking water generally filtered through treatment plants. In addition, it is harder to relocate from a polluted airshed than it is to substitute between nearby clean and dirty rivers for recreation.

Nevertheless, the researchers suggest that other amenity values might justify the costs of the grants. For instance, while on a high school band trip from Southwest Virginia in 1970 I recall vividly walking down to the Potomac River at Mount Vernon to see a sign bobbing in the water warning against coming in contact with the water as it was dangerous to one's health. I have now enjoyed many pleasant days boating and sailing on the cleaned up river. In addition, as pollution has abated American cities that once turned inward from their polluted waterfronts have transformed those areas into high rent neighborhoods and entertainment districts.

In addition, to the reductions in the EPA's air and water pollution programs, the Trump budget would cut by $330 million the Superfund program that is supposed to clean up specific hazardous waste sites like abandoned dumps and industrial plants. The program sparks a great deal of litigation that boosts costs and slows clean up. One 1999 study estimated that Superfund remediation would on average avert less than 0.1 case of cancer per site and that the cost per cancer case averted is over $100 million. As Case Western Reserve University law professor Jonathan Adler has argued, "Contamination of soil and groundwater are site-specific, rarely crossing state lines. Due to the local nature of hazardous waste problems, state governments should be given the opportunity to assume leadership of hazardous waste regulation and cleanup." In line with that recommendation, the Trump budget document, instructs the EPA to "look for ways to remove some of the barriers that have delayed the program's ability to return sites to the community."

One other observation: The Trump budget would eliminate the EPA's Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program. Good riddance. Billions of dollars have been spent pursuing the so-called endocrine disruption hypothesis in which trace exposures synthetic chemicals are supposedly causing hormone havoc in people. Two decades of research has comprehensively debunked it. "Taking into account the large resources spent on this topic, one should expect that, in the meantime, some endocrine disruptors that cause actual human injury or disease should have been identified," a group of European toxicologists assert in 2013 review article. "However, this is not the case. To date, with the exception of natural or synthetic hormones, not a single, man-made chemical endocrine disruptor has been identified that poses an identifiable, measurable risk to human health."

Of course, state and local governments will decry the proposed cuts in the EPA grants they expected to receive. Federal dollars are generally treated as "free money" enabling local officials to avoid having to make hard tradeoffs between various programs and amenities and raise state and municipal taxes to pay them. Whatever the achievements of EPA programs in the past – don't forget that rates of air and water pollution abatement didn't actually speed up after the creation of the agency in 1970 – we are well past the point of rapidly diminishing returns when it comes to additional pollution abatement. It is the right moment to make states and municipalities more responsible and responsive to their local citizens when it comes to handling environmental concerns and issues.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Sounds kind of porny.

federal air quality regulation suffers from incentives to create requirements that are unnecessarily stringent, intrusive, bureaucratic, and costly

features, bugs; to-may-to, to-mah-to

"federal air quality regulation suffers from incentives to create requirements that are unnecessarily stringent, intrusive, bureaucratic, and costly"

Which makes it no different than any other federal state or local government regulatory scheme that oversees any aspect of existence.

GM: Alas, yes.

Ron, do you think we can call for the elimination of all current top-down climate change regulations without implementing a Carbon Tax?

T: I don't do politics - I do policy. In any case, see my note on the carbon dividend proposal that would do largely what you suggest.

I have read it. This is the proposed policy from The Climate Leadership Council, that I am curious if you endorse, as it appears you do in the article=

Carbon dividends? Seriously? Come on Ron. You and I both know that any tax implemented by the government will never be matched by offsetting reductions elsewhere. This proposal is about as anti-libertarian as they come, yet you defend it as such and I don't understand why.

Help me understand, I just don't get what is so libertarian about proposing a Carbon tax.

T: You and I both know that any tax implemented by the government will never be matched by offsetting reductions elsewhere.

Like I said, I don't do politics. You might want to look at the interview with me the folks at Yale Climate Connections did.

I am trying to discuss policy with you, the policy of Carbon tax in particular, and you seem to want to evade the question:

Is a Carbon Tax good libertarian policy? Is there a quantifiable method for measuring the results of a Carbon Tax policy? Will this policy be effective in managing the effects of climate change any better than the current market solutions that have come through fracking and the increased use of cheap natural gas?

I'm not asking political questions, I just don't understand where you're coming from with the Carbon tax policy.

T: Assuming that man-made climate change could well become a significant problem later in this century, what would you propose to do about a global-scale open access commons problem?

If you don't think that climate change could become a problem, then there simply is no need for any policy.

R: For the sake of argument I will agree with you that yes- man-made climate change could well become a significant problem later in this century.

So my answer to the global-scale open access commons problem is first: do no harm. Proposing tax policy that will not be adopted by a majority of the world is a non-starter. Asking nations to slow down their march towards Western world levels of prosperity is also a non-starter. What I would suggest is reviewing policies that have produced results that lower CO2 emissions. Fracking has produced cheap natural gas that has helped lower our use of other fossil fuels for electricity, thus lowering said "carbon footprint".

What I would definitely NOT propose nor support is a policy that attempts to use economic incentives and regulations to force industries to artificially hamstring their production in order to meet goals for reducing emissions.

T: Take a look at my 2009 analysis "What's the Best Way to Handle Future Climate Change?"

Among other things, I note:

Under a pollution tax scheme, argues Yale economist William Nordhaus, "The natural baseline is a zero-carbon-tax level of emissions, which is a straightforward calculation for old and new countries. Countries' efforts are then judged relative to that baseline."

Another advantage is that the tax could be phased in as the average incomes of poor countries reach a certain threshold. For example, carbon taxes might start to kick in when national income reaches $7,000 per capita, which is slightly higher than China's current level. More generally, having a defined tax rate makes it easy for firms in developed and developing economies alike to predict the future impact of climate policy on their bottom line?something that is considerably harder to do when the government is handing out permits every year.

A tax avoids the messy and contentious process of allocating allowances to countries internationally and among companies domestically.

After we get this wonderful carbon tax can we burn all the witches?

GF: Only if the emissions from the burning are taxed. 🙂

Maybe you could assume that alien invasion might be a problem later this century. There is just about as much evidence of that as there is CAGW. Until someone can estimate climate sensitivity accurately - which at the moment no one can...though the estimates do seem to be going down - then CAGW is just a fairy tale.

"Relax: Gutting the EPA Won't Make Your Air Dirtier and Water More Polluted"

This is gonna sell like tickets to a Milo appearance in the oh-so-sciency SF bay area.

Do we rely on states having better standards? We saw how EPA failed in acting as a counter to MI's flint lead water issue. The solution is to make EPA worse? Some states compete for industry and to one up the other state end up condoning local regulations that are weak on holding companies responsible for their runoffs.

Absolutely, they need more money so they can fail harder.

"We saw how EPA failed in acting as a counter to MI's flint lead water issue. The solution is to make EPA worse?"

So the wrong Top Men were running the show?

EPA failed to act?

I get the EPA hate, but it's my understanding that it was an EPA guy who finally waved the flag hard enough for others to notice. Flint's problem started with voters, who in recent decades only choose Democrat politicians, who completely failed at the local level. The disaster in Flint was a Democrat production, not EPA's.

"EPA failed to act?

Oh, they 'acted, alright:

"The Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) top Midwest official knew about the Flint, Michigan drinking water crisis of 2015 months before telling the public, according to a Tuesday report by the The Detroit News.

EPA official Susan Hedman did not publicize the EPA's concern over Flint's water quality or the water's dangerous health concerns. The federal agency instead quietly fought with the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality for at least six months about what should be done.

http://dailycaller.com/2016/01.....he-public/

When you have a department that doesn't work, you close that department. It's not rocket surgery.

The problem is you are assuming having more money make them better. It wasn't the EPA that really failed if i recall, but rather the Michigan DEQ forgot to add phosphates. The issue was the dwellings themselves (the pipes) so it wasn't any company that did a runoff causing it...it was the water getting rid of the protective layer since the phosphates weren't added.

The EPA needs to be a quality and strict scope, not a jack of all trades master of none.

To praveen

Should they be given more money since they didn't catch it

RB-

on that toxicology report wrt endocrine disruptors. that study should come with a disclaimer that the lead researcher works for L'Oreal. otherwise when we cite it to all our crazy friends we're not smacked upside the head with that little conflict of interest.

http://www.eurotox.com/sub/eur.....ohynek.pdf

In 1997, ?he ?joined? L'OREAL ?and? currently ?holds ?the ?position ?of? Scientific ?Director? of? the? Global Safety? Department? of? L'OREAL? Research? &? Development.?

RB: Thanks much for bringing this to my attention. I agree that the conflicts of interest statement at the end of the article is a bit too clever.

On the other hand, I direct your attention to my chapter 4 in The End of Doom on toxicology where I have an fairly extensive analysis of the endocrine disruption hypothesis in which I conclude that it is an example of "pathological science."

You may also be interested in my longer disquisition on conflicts of interest in my report for the American Council on Science and Health, Scrutinizing Industry-Funded Science: The Crusade Against Conflicts of Interest

I point out: The plain fact of the matter is that there is very little evidence that alleged conflicts of interests are significantly distorting scientific research, harming consumers and patients or misleading public policy. Most conflicts of interest activists clearly have prior strong ideological commitments against markets and corporations. They view the conflicts of interest campaign as another tool to attack an enterprise which they already despise on

other grounds.

RB: One more thing on conflicts of interest:

I am still trying to get behind the paywall, but a comprehensive new PNAS study by the incomparable John Ioannidis reports that the greatest source of bias was small studies whereas sponsorship has a much smaller effect.

that is interesting.

Conflict of interest

The opinions forwarded in the article represent personal opinions

of the authors and are proposed with the aim to improve the

safety assessment of personal care products. The authors received

no support or compensation for writing the article. They therefore

declare no conflict of interest.

Clever? At best, it is incomplete. At worst, unethical.

Chicago...adopted smoke abatement ordinances in 1881.

Yeah, that was all about the quality of the air and not a reaction to other recent events.

One way to cut the EPA budget would be to get rid of its regulatory function, confining it to enforcement of existing law. They should also be require to obey the law themselves, as they often fail to do (e.g., the Colorado gold mine spill).

I always find it amusing how the opponents of clean air/water legislation try to argue, in the same breath, that:

A) Regulation XYZ is onerous and is hurting businesses by having to abide by it, and

B) We shouldn't worry about removal (or cessation of enforcement due to gutting the regulator) of Regulation XYZ because... well, hey... these businesses aren't evil. They're run by 'mericans! They'd never *dream* of dumping hazardous waste into our streams!

You can't have it both ways. If you argue that a regulation is onerous or oppressive, then you're admitting that it's forcing people to act differently than they would were that regulation not in place... which, then, means that, if the regulation were *not* there, they'd be acting in ways which the regulation forbids.

So, this notion of "The federal regs aren't needed because the states are already seeing to it"... if that were the case, then why would so many business be wanting to kill the EPA if doing so wouldn't loosen the reins?

"I always find it amusing how the opponents of clean air/water legislation try to argue, in the same breath, that:

A) Regulation XYZ is onerous and is hurting businesses by having to abide by it, and

B) We shouldn't worry about removal (or cessation of enforcement due to gutting the regulator) of Regulation XYZ because... well, hey... these businesses aren't evil. They're run by 'mericans! They'd never *dream* of dumping hazardous waste into our streams!"

I find it amusing that lefties are forever inventing straw men to justify their love of coercion.

Yes, a regulation requiring the removal of lead to the tenth decimal place is onerous, and no, I'm not worried that a company would dump enough in to cause problems; they'd get their ass sued.

BTW, fuck off, slaver.

JE: Two words: Diminishing returns. Two more words: Benefit-cost.

I think this title doesn't capture your caveat of suggested shifted responsibilities within our federal system:

"Relax: Gutting the EPA Won't Make Your Air Dirtier and Water More Polluted*"

*If your state and/or municipality have the scientific expertise to assess the pollutiuon, the political indepenence from prominant local industries to regulate it, sufficient empathy for the segment of the population impacted, and the financial wherewithal execute said regulation or cleanup.

*If not, sucks to be you.

I was thinking of California, the richest of rich states with water infrastructure that's literally falling to pieces. Now imagine if the issue was smokestack emissions instead of water. Trusting other states to do what's right would be profoundly naive. Some level of federal oversight seems appropriate and compatible with the Commerce Clause, the original intent of which was to give the federal government sufficient power to stop states from harming other states.

Faith in the court system to make things right after kids across the state line are made retarded by heavy metal emissions doesn't strike me as the right approach.

Johnniest Doe|3.21.17 @ 9:05PM|#

"I was thinking of California, the richest of rich states with water infrastructure that's literally falling to pieces."

So we have the richest state with the most intrusive regulations and that's not enough so we need more of them?

Suggestion: When you've dug the hole up to your eyeballs, stop digging. It's not going to get better.

On that EDSP, the EPA page you linked to indicates that "Congress passed the Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA), which amended the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA), and the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) Amendments in 1996. FQPA requires that EPA screen pesticide chemicals for their potential to produce effects similar to those produced by the female hormones (estrogen) in humans and gives EPA the authority to screen certain other chemicals and to include other endocrine effects."

I get the EPA hate and all that, but if, in fact, this program (or something like it) is required by statute, isn't that something Congress would have to address before the Executive could just arbitrarily start failing to faithfully execute?

JD: But what if Congress chooses not to fund the program?

Prosecutorial discretion. That means the feds do what they want, when they want, or not, as they want. Quit expecting the law to be followed unless it is a "good" law from "good" democrats.

my Aunty Isabella got an awesome six month old BMW 6 Series Gran Coupe Sedan only from part-time off a computer... Look At This?????O FREE JOB VISIT FREE

"In addition, as pollution has abated American cities that once turned inward from their polluted waterfronts have transformed those areas into high rent neighborhoods and entertainment districts."

Which will be immediately flooded due to global warming, or maybe climate change. So the EPA is causing thousands of deaths.

I think we must think more about air pollution. We can blame population growth, the oil and gas industry, vehicle pollution and coal-fired power plants for the elevated ozone, for which Front Range air has been deemed out of compliance with federal health standards. But something must be done. I was pushed to look for denver air conditioning co ( http://www.summitheatingco.com/ ) to install a new filter and conditioning system in my denver house. Because this year denver was pushed from 26th to 13th among most-polluted cities in the nation. Denver's air is deteriorating, with increased ozone and soot, and a lot of people live there.