When SCOTUS Stopped a Government-Led Attack on Freedom of the Press

Revisiting a landmark First Amendment case.

In 1934 the Louisiana legislature passed a law requiring all newspapers, magazines, and periodicals with a circulation of 20,000 or more to pay an annual licensing tax of 2 percent on all gross receipts "for the privilege of engaging in such business in this State." Ostensibly justified as just another run-of-the-mill tax, the measure's true purpose was plain for all to see. The governor at that time was the notorious populist demagogue Huey P. Long, also known as the "Kingfish." The Long administration was famously rife with corruption and criminality and the state's biggest newspapers just happened to be some of the governor's most outspoken critics. So the Kingfish told his allies in the legislature to use the state's vast taxing powers to harass and punish his enemies in the press.

The American Press Company, along with eight other newspaper publishers, promptly filed suit, charging the Long administration with waging an illegal war on the freedom of the press. Their case, ultimately known as Grosjean v. American Press Co., arrived at the U.S. Supreme Court in 1936. The resulting decision stands as one of the great First Amendment rulings of its time.

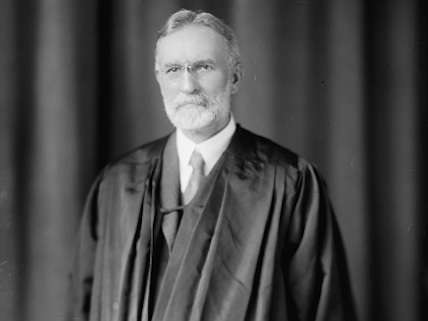

The majority opinion was written by Justice George Sutherland, a jurist of classical liberal tendencies who is best remembered today as the intellectual leader of the so-called Four Horsemen, the bloc of justices who regularly ruled against New Deal legislation in the 1930s. Sutherland was no fan of what he called "meddlesome interferences with the rights of the individual," and he made no effort to hide his dismay at the unconstitutional behavior of the Pelican State.

The Louisiana law is "a deliberate and calculated device in the guise of a tax to limit the circulation of information to which the public is entitled in virtue of the constitutional guarantees" set forth in the First Amendment, Sutherland declared. "A free press stands as one of the great interpreters between the government and the people. To allow it to be fettered is to fetter ourselves." The law was invalidated 9-0.

Grosjean v. American Press Co. still resounds today as a landmark defense of the freedom of the press. But Sutherland's majority opinion accomplished even more than that.

Nowadays we take it for granted that the provisions contained in the Bill of Rights impose limits on both federal and state officials. But that was not always the case. When the batch of amendments that comprise the Bill of Rights were first added to the Constitution in 1791, those amendments were understood to apply solely against the federal government; they did nothing to bind the states. For illustration, consider the opening text of the First Amendment, which is quite explicit on this point: "Congress shall make no law."

But things changed in 1868 with the ratification of the 14th Amendment, which forbids the states from infringing on the privileges or immunities of citizens and from denying any person the right to life, liberty, or property without due process of law. What does that sweeping language mean? According to Republican Senator Jacob Howard of Michigan, who introduced the 14th Amendment in the Senate in 1866 and then spearheaded its passage in that chamber, it was designed to protect both certain unenumerated rights (such as economic liberty) as well as "the personal rights guarantied and secured by the first eight amendments of the Constitution." The purpose of the 14th Amendment, Howard explained, was "to restrain the power of the States and compel them at all times to respect these great fundamental guaranties."

Yet the Supreme Court did not give the First Amendment its due under the 14th Amendment until the 1925 case of Gitlow v. United States, in which the Court first held that "freedom of speech and of the press—which are protected by the First Amendment from abridgment by Congress—are among the fundamental personal rights and 'liberties' protected by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment against the states."

Gitlow was still in its relative infancy 11 years later when the censorious Louisiana newspaper tax arrived at the Supreme Court. Which brings us back to Justice Sutherland. His majority opinion in Grosjean v. American Press Co. both reinforced the Gitlow holding and extended its reach. "Certain fundamental rights, safeguarded by the first eight amendments against federal action… [are] also safeguarded against state action," Sutherland declared. "Freedom of speech and of the press are rights of the same fundamental character."

In sum, Grosjean v. American Press Co. is a good precedent to have on the books. Not only does it tell power-hungry politicians to respect the freedom of the press, it compels all levels of government to obey the First Amendment.

Show Comments (14)