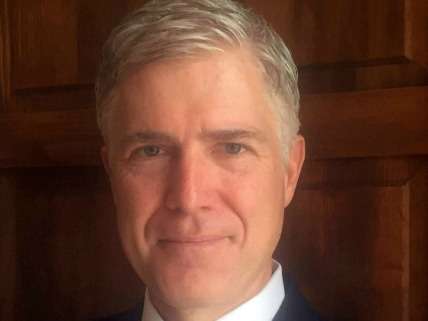

Neil Gorsuch Follows Justice Scalia's Footsteps on Criminal Justice

Civil libertarians have reasons to be pleased with Trump's SCOTUS pick.

If you were hoping President Donald Trump would pick someone to follow in the late Justice Antonin Scalia's footsteps, you should be happy with his selection of Neil Gorsuch. Like Scalia, Judge Gorsuch is a brilliant thinker, gifted writer, dedicated constitutionalist, defender of the separation of powers, and a judge willing to stand up for the rights of unpopular defendants if that's what the law requires.

I've written before about Justice Scalia's surprising (to some) opinions in which he defended the constitutional rights of criminal defendants, even though it was clear that Scalia the private citizen was a law-and-order guy. Scalia was especially impatient with vague criminal statutes that, he believed, failed to provide individuals with fair warning of the type of misconduct that might land them in prison.

In Sykes v. United States (2011), Justice Scalia railed against a vague provision of the Armed Career Criminal Act, a federal law that imposes lengthy mandatory minimum prison terms:

We face a Congress that puts forth an ever-increasing volume of laws in general, and of criminal laws in particular. It should be no surprise that as the volume increases, so do the number of imprecise laws. And no surprise that our indulgence of imprecisions that violate the Constitution encourages imprecisions that violate the Constitution. Fuzzy, leave-the-details-to-be- sorted-out-by-the-courts legislation is attractive to the Congressman who wants credit for addressing a national problem but does not have the time (or perhaps the votes) to grapple with the nitty-gritty. In the field of criminal law, at least, it is time to call a halt.

Four years later, Scalia prevailed upon his colleagues and led the majority to strike down the fuzzy provision that offended his sense of fairness. The Due Process Clause, he wrote for the Court, prohibits the government from "taking away someone's life, liberty, or property under a criminal law so vague that it fails to give ordinary people fair notice of the conduct it punishes, or so standardless that it invites arbitrary enforcement."

Judge Gorsuch clearly shares Scalia's concern about vague criminal laws. In U.S. v. Games-Perez (2012), Gorsuch confronted the federal criminal law that prohibits felons from knowingly possessing firearms. The issue before Gorsuch's court was whether a conviction should be secured so long as the defendant knew he possessed a firearm, or, should the government be required to also prove that the defendant knew he was a felon when he did so.

A Scalia-minded textualist, Gorsuch argued that the "text of the relevant statutes" clearly put that burden on the government. And when a majority of his colleagues on the 10th Circuit panel found otherwise, Gorsuch opened his dissent with a strong statement about the very real harm individuals endure because of the court's misreading of the law:

People sit in prison because our circuit's case law allows the government to put them there without proving a statutorily specified element of the charged crime. Today, this court votes narrowly, 6 to 4, against revisiting this state of affairs. So Mr. Games-Perez will remain behind bars, without the opportunity to present to a jury his argument that he committed no crime at all under the law of the land.

Like Scalia, Gorsuch is not known to have a soft spot for armed criminals. But also like Scalia, he believes that courts should err on the side of individual liberty when interpreting vague criminal laws. In fact, in a speech to the Federalist Society in 2013, Judge Gorsuch echoed Scalia's attack on overcriminalization in Sykes. Gorsuch said:

When he led the Senate Judiciary Committee, Joe Biden worried that we have assumed a tendency to federalize, 'Everything that walks, talks, and moves.' Maybe we should say 'hoots' too, because it's now a federal crime to misuse the likeness of Woodsy the Owl. (As were his immortal words: 'Give a hoot, don't pollute!') Businessmen who import lobster tails in plastic bags rather than cardboard boxes can be brought up on charges. Mattress sellers who remove that little tag? Yes, they're probably federal criminals too.

Whether because of public choice problems or otherwise there appears to be a ratchet, relentlessly clicking away, always in the direction of more, never fewer, federal criminal laws. …

But isn't there a troubled irony lurking here in any event? Without written laws, we lack fair notice of the rules we as citizens have to obey. But with too many written laws, don't we invite a new kind of fair notice problem? And what happens to individual freedom and equality when the criminal law comes to cover so many facets of daily life that prosecutors can almost choose their targets with impunity?

Matters of criminal law are not the only bases on which to judge a judge, but they can be very telling because the conduct at issue is often unsavory and public opinion is often on the opposite side of the law. In numerous cases, Justice Scalia showed that his fidelity to constitutional protections outweighed any personal biases he carried about suspected or convicted criminals. There are good reasons to believe Judge Gorsuch will act with similar restraint and humility. And that is one reason why Scalia's admirers are happy with Gorsuch's nomination.

Show Comments (73)