What David Brooks Doesn't Know About Social Movements

Brooks thinks "most of the time change happens through political parties." He's wrong.

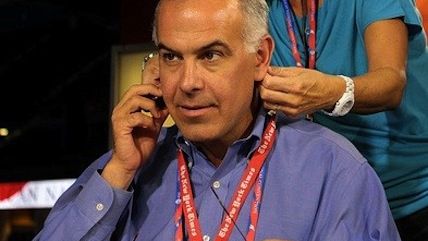

You can call off the hunt; I think we've found the most tedious take on last weekend's anti-Trump marches. The perp is David Brooks, and the axe-grinding argument that looks set to win the prize begins in the fifth paragraph of his New York Times column today:

[T]here was too big a gap between Saturday's marches and the Democratic and Republican Parties.

Some of us were wondering whether the movement can avoid being coopted by party hacks. Brooks was wishing there were more hacks on the scene.

Sometimes social change happens through grass-roots movements—the civil rights movement. But most of the time change happens through political parties: The New Deal, the Great Society, the Reagan Revolution. Change happens when people run for office, amass coalitions of interest groups, engage in the messy practice of politics.

I shouldn't have to point this out, but there are countless cases of social changes that built up in civil society before they entered party politics in a serious way. Gays, to take an obvious example, were carving out space for themselves—even forging same-sex marriages—long before any established party politicians adopted their cause. The counterculture transformed social mores years before any ex-hippie got elected to anything; the Christian counter-counterculture certainly learned how to use party politics, but it was a grassroots social movement before it was a movement at the polls. And since the central theme of Saturday's marches was feminism, let's note that the nuclear family and other traditionally patriarchal institutions were being transformed well before they became sites of political agitation (Alan Petigny's terrific book The Permissive Society has more on this), and that this agitation in turn affected social spaces far larger than those touched by party politics.

Needless to say, independent social movements have also proven themselves useful even when conventional politicians are on their side, by applying the pressure necessary to keep those pols' priorities in line with the protesters' preferences. Other times activists decide to work within the system in ways that essentially ignore party politics, as the ACLU and the Institute for Justice do when they challenge laws in court. Or they win a victory in a referendum while the parties mostly keep their distance, as the marijuana movement has in several states. And of course, many epochal social transformations are driven by forces outside either movements or parties, as any historian of technology could tell you. It's absurd to treat these many means of change as though they're marginal sidebars in a story dominated by Franklin Roosevelt, Lyndon Johnson, Ronald Reagan, and their loyal foot soldiers.

Without the discipline of party politics, social movements devolve into mere feeling, especially in our age of expressive individualism. People march and feel good and think they have accomplished something. They have a social experience with a lot of people and fool themselves into thinking they are members of a coherent and demanding community. Such movements descend to the language of mass therapy.

There's no denying that many movements have done exactly this. But it takes a rather blinkered view to think that only party politics can bring discipline to a movement. In any case, discipline is hardly the only factor that matters. What Democrats lacked on Election Day wasn't discipline; it was enthusiasm. Liberated from a terrible standard-bearer, they now have generated enthusiasm in spades. There just might be a lesson here.

Clearly there are big questions about whether and how Saturday's marchers will channel their energy into blocking Trump's agenda, let alone working toward a positive agenda of their own. But the fact that they were able to turn out so many people—and with so many homemade signs, as opposed to the mass-produced placards that dominate so many smaller protests—is a clear sign that the energy is out there. I really doubt that putting more elected officials onstage would have helped.

It's significant that as marching and movements have risen, the actual power of the parties has collapsed. Marching is a seductive substitute for action in an antipolitical era, and leaves the field open for a rogue like Trump.

The power of the parties started crumbling in the 1970s. I'd be very interested in Brooks' evidence that "marching and movements have risen" in tandem with their collapse. Extra credit if his explanation has room for, say, the strikes of the Depression era.

So there you have it: David Brooks on social movements. It's hard to imagine a more tedious reaction than—

Hold on, I've found a worse one. Ladies and gentlemen, I give you the final two paragraphs of Brooks' column:

If the anti-Trump forces are to have a chance, they have to offer a better nationalism, with diversity cohering around a central mission, building a nation that balances the dynamism of capitalism with biblical morality.

The march didn't come close. Hint: The musical "Hamilton" is a lot closer.

Show Comments (156)