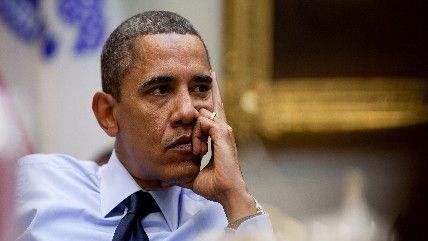

President Obama Thinks He Did a Great Job With Criminal Justice Reform, But He Should Have Done More

Obama is in full legacy-preservation mode in article for Harvard Law Review.

President Obama published a commentary today in the Harvard Law Review titled "The President's Role in Advancing Criminal Justice Reform." In one sense, Obama is clearly trying to telegraph to thought-leaders how he believes his legacy regarding one of his key issues should be remembered. In another sense, the article is a pre-emptive warning to anyone concerned with mass incarceration, police-community relations, sentencing reform, and other related issues that they might not have realized how good they had it under the Obama administration.

Sure, Obama cherry-picks his data, omits any relevant but inconvenient information that might damage his narrative—he doesn't touch the war on drugs or marijuana legalization at all—but it is easy to understand who Obama is addressing. This isn't a paper that will be widely read by the public, this is for the academics and think tankers who will be among the first to determine where Obama's legacy ranks in the pantheon of American presidencies.

In the 56-page commentary, Obama writes "Criminal justice reform has been a focus of my entire career — even since before my time at the Harvard Law Review" a reference to his tenure as the first African-American president of the august legal publication.

Obama writes, "I will be the first President in decades to leave office with a federal prison population lower than when I took office even as my Administration saw the rate of violent crime fall to its lowest point in decades," and also credits his administration with helping to reduce sentences for non-violent offenders, make it easier for people with a criminal blemish on their record to gain employment and education, and also helping young people "avoid getting entangled in the justice system in the first place."

Among other reform achievements cited are the Justice Department's 2010 decision to reverse "a policy requiring prosecutors in every case to bring charges that could result in the most severe possible sentence," as well as its instruction to federal prosecutors to stop threatening defendants in drug cases with enhanced charges based on previous drug convictions as a means of gaining leverage in plea negotiations.

Donald Trump gets some none-too-subtle shade thrown his way by Obama over his tendency to emotionally react on Twitter when hot-button news stories break.

Obama writes that "presidents are not private citizens" and thus, when "a viral YouTube video…leads the evening news, incites protests, and drives calls for reform," the commander in chief needs "to be careful about speaking about legal matters before all the facts are in—even if it appears that everyone else in the United States is commenting on them."

The president tosses some red meat to the gun control faithful with vague rhetoric about "smart guns," "background checks," and other "commonsense steps to reduce gun violence." He also rails against solitary confinement, zero tolerance polices at school, and excessive bail practices. Also included among his "work unfinished," Obama calls for more transparency and better practices regarding police body cams, treating the opioid crisis as a public health issue, and restoring the right to vote for ex-convicts.

Obama boasts of expanding access to substance abuse treatment through Obamacare, but is willing to spread some of the credit around, like when he touts the "red states" of Alabama, Georgia, and Texas for leading and innovating:

By reducing sentences and reinvesting some of the savings in other public safety initiatives — especially programs that actually address substance abuse and support for those with mental illness — these states have improved outcomes, enhanced trust, and thus ultimately made better use of taxpayer dollars.

The president touches upon his Task Force on 21st Century Policing, launched in 2014, which among other things called for greater cooperation from the 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the United States in providing accurate data to the FBI regarding the use of force by police.

Although Obama writes "this voluntary collection has the potential to make the use of force even more rare and the devastating consequences of force even less likely," he fails to mention that his Justice Department has had three years to enforce the Death in Custody Reporting Act of 2013, but to date the DOJ has not sanctioned even one non-compliant department with the loss of federal law enforcement grant funds as stipulated by the law.

Obama cites a "wide range of research and policy initiatives to strengthen the forensic sciences, spanning disciplines from DNA analysis and fingerprints, to tire and tread marks, ballistics, handwriting, trace-evidence and toxicological analyses, and digital evidence" and warns that "forensic science disciplines are subject to varying degrees of uncertainty and misinterpretation," which appears to be a concession by the president that innocent people have been imprisoned because of "bad science."

What Obama fails to mention is that his own Attorney General Loretta Lynch was an obstacle to this particular opportunity for reform, putting her faith in law enforcement ahead of science. Former Reasoner Radley Balko notes in The Washington Post:

Obama can tout the committees he formed and the reports he commissioned all he likes. When it came to using those reports to actually improve the criminal-justice system, his own attorney general rejected the notion out of hand. Obama then failed to correct her. As I wrote Wednesday, the window for reform here is small. Obama had the evidence to demand it. He's a lame-duck president in an era where the public is as skeptical of the criminal-justice system as it's been in generations. It was a golden opportunity. We just happened to have someone in the White House who, at least in his rhetoric, seemed to understand these issues as well as anyone we could really ever hope for — and at a time when the conditions for reform are as favorable as they're ever likely to be.

The president's commentary contains another noteworthy omission: there's nothing in there about the legal status of marijuana.

This is somewhat understandable. After all, it is primarily an essay where Obama wants to take credit for things, and he knows he really deserves no credit for the growing trend of states legalizing both medical marijuana and recreational marijuana. After raiding more medical marijuana dispensaries in his first term than George W. Bush did in two terms, and after refusing to have the DEA reschedule marijuana off of Schedule I, perhaps Obama wants to wait until he's out of office before using the bully pulpit of an ex-president to advocate for the legalization of a drug he has already admitted he believes is less harmful than alcohol and should regulated similarly.

Still, Obama's choice to ignore the ongoing federal criminalization (and evolving local status) of a drug he once used heavily in a prestigious victory lap essay about "reform" is both a missed opportunity and fairly infuriating from a criminal justice reform standpoint. Ex-presidents have influence, but they don't have power. The time to act was then, not later.

President Obama indeed deserves a good amount of credit from criminal justice reformers, but he ultimately could have—and should have—done more.

Show Comments (170)