HBO Documentaries Illuminate Castro's Brutal Cuba

Two offerings coincide with strongman's death.

Patria O Muerte: Cuba, Fatherland or Death. HBO. Sunday, December 4, 9:45 a.m.

Mariela Castro's March: Cuba's LGBT Revolution. HBO. Tuesday, December 6, 5 p.m.

HBO should get a little trophy from the television industry for giving executives something to talk about at holiday parties besides falling ratings and the specific level of Hell that should be reserved for whoever invented this internet thing. Instead, they can ponder over the question: Is HBO's documentary division the most genius outfit in television, or just the luckiest? Months ago, HBO acquired two unheralded documentaries on Cuba, then booked them for the very moment when Fidel Castro would head off to the great workers' collective in the sky. Water-cooler buzz galore, Latin American Policy Wonk Department.

And if that department had an Emmy, Patria O Muerte: Cuba, Fatherland or Death would win it right now. First-time director Olatz López Garmendia is better known as a model and a fashion designer, but she must have had a career in operating heavy construction equipment, too, because Patria O Muerte takes a merciless wrecking ball to the Potemkin Village imagery of Cuba promoted by most of the American chattering class. The desolation and despair of Castro's Revolution—its actually existing socialism, as Marxist theoreticians of the 1950s would have called it—has never been on such devastating display for American audiences.

Garmendia lived in Cuba as a child, when her Spaniard parents joined the flocks of European Fidel groupies moving to Havana to stand by their man, but she clearly didn't swallow the Kool-Aid; Patria O Muerte is not her first demythology project on Cuba.

She also informed the sensibilities of her then-husband, Julian Schnabel, when he was making his epic anti-Castro movie Before Night Falls. (Garmendia worked on the film as music supervisor.) She made Patria O Muerte as something of a samizdat work; the film was shot without Cuban authorization, and she had a devil of a time getting the footage off the island.

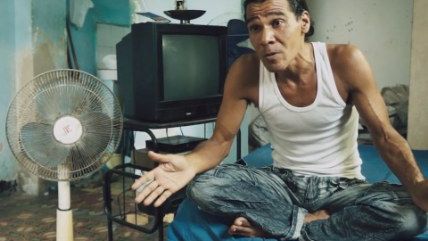

Without narration and little archival footage, Patria O Muerte makes its points through a series of interviews of ordinary Cubans, filmed in their seedy tenement apartments in Old Havana. The stories they tell, with only occasional exceptions, are not of lurid torture or persecution, but of the quiet desperation of life in a dead-end society weighed down by decay of every type: economic, physical, mental.

There's a cadaverous old man named Julio who bluntly declares his life useless and is clearly talking about more than his grubby apartment when he responds to a question: "What am I missing? Everything." Or Valery, a goth transvestite who took to the streets as a jinatera, as the island's part-time hookers are known, after the remittances from a sister in the United States dried up and she found herself without enough money to buy a new toothbrush. That career ended, though, one night after she was lectured by a tourist whose appreciation for cheap commercial sex had not diminished his more-revolutionary-than-thou ardor for the Castro regime. He told her that "Cubans were shameless, that Cubans said they had problems, when there weren't any problems in Cuba." Retorted Valery: "If that's true, then what am I doing here with you for $20?" She left the streets, fearful that she was "about to kill [herself], or kill one of these foreigners."

Or Mercedes, a housewife living in a tottering building built in the 1870s in which she must sleep with one eye open to avoid being hit by chunks of falling masonry. Her young son, injured in a balcony collapse, needs surgery, but building repairs make it impossible: "If we buy cement, then we can't buy food or medicine." An aphorism which, oddly, didn't make it into Sicko, Michael Moore's encomium to the Cuban health-care system.

Garmendia shot some interviews with dissidents, too, including rogue blogger Yoani Sanchez, whose contribution of an audio tape of her 2010 detention by men without uniforms or credentials is by far the most chilling moment in the film. Unfortunately, her cameras weren't along when one of her subjects, graffiti artist El Sexto, was arrested when found in possession of a couple of pigs painted with the names Fidel and Raul.

Patria O Muerte's companion piece, Mariela Castro's March: Cuba's LGBT Revolution, is a far better film than I would have guessed, given it's a project of longtime Castro apologists Saul Landau and Jon Alpert. But it has to be given credit as the first English-language documentary to discuss, however briefly, the regime's brutally harsh treatment of homosexuality during the 1960s and 1970s.

There was no shortage of official homophobia around the globe at that time, of course, particularly in the machista world of Latin America. But few counties took it to the extremes of Cuba, where gays were locked up in work camps for years at a time.

"Look at me here, with bright shiny eyes," says one elderly gay man, brandishing what looks like an old graduation photo. Then he opens the internal passport the government issued him after two years in a work camp: "The camp changed that for the rest of my life. … My eyes are vacant and sad." They would become sadder still; the passport was marked with his sentence to the work camp, Castro's equivalent of a pink triangle that doomed any social or professional prospects.

But that rare and valuable look at a largely unseen side of Cuban history is over in a few short minutes. The rest of Mariela Castro's March is about the budding movement for gay acceptance being led by the daughter of Raul Castro. It has its oddly charming moments, including an interview in which Cuba's first female-to-male transgender surgery patient displays his bulging new package, which he's named Pancho, and proclaims: "Pancho works perfectly!" Grumbles his elderly brother: "I'm jealous."

Yet too much of this documentary is suffused with the cult of personality that colors everything about the Castros. And there's no awareness—on the part of the filmmakers or the movement activists, though the latter may simply be exercising reasonable prudence—of the irony of seeking liberty in one small sphere of Cuban life while ignoring the crushing totalitarianism of everything else. "I can shout that I'm gay and nothing happens!" boasts one giddy man. Yeah, but trying painting "RAUL" on a pig's butt and see what happens.

Show Comments (91)