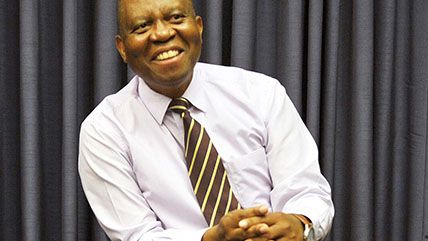

Meet Johannesburg's New Libertarian Mayor

Herman Mashaba is something new in South Africa. But can a black pro-market politician make real changes?

Herman Mashaba is an unlikely mayor for South Africa's largest city. In a country that has been dominated for more than two decades by the left-wing African National Congress (ANC), no one foresaw political victory for a self-declared "capitalist crusader," property rights zealot, and beauty products mogul who opposes the minimum wage and zoning regulations. Mashaba is an outlier even in his own party, the white-dominated centrist Democratic Alliance (D.A.).

The son of a domestic worker raised by his sisters in a black township near Pretoria under apartheid, Mashaba became a self-made millionaire in a country that systematically excluded blacks from economic opportunities. Sworn into office on August 22, he must wrangle a coalition that includes the revolutionary socialist Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) as he tries to implement an anti-regulation, pro-market agenda.

reason: Under apartheid, the white government claimed to be capitalist. So many black South Africans support parties that are critical of free markets, such as the ANC, or explicitly anti-capitalist, like EFF. What explains your pro-market stance?

Mashaba: In 1950, they passed the Suppression of Communism Act. So when I was born in 1959, by virtue of that law and being black, I was automatically a communist. Look at that piece of legislation. It says that anyone that advocated the rights of blacks must be regarded as a communist.

What compounded the problem was that as we were growing up, the communists were the ones that seemed to be helping us, and on the other hand the Americans and the British were seen to be working with the apartheid government. So as far as blacks were concerned, Russia was the savior.

People had no idea what Russia was doing to its own people. If you saw the mess that was happening in Russia—our people had no idea. But the ANC guys who had been to Russia, they knew how brutal the system is.

In 1980, with my university closing down, I tried to leave the country to go for military training. I was hoping the Russians would give me an AK-47 and train me. I had nothing to lose; the apartheid government wanted to destroy my future and my life.

reason: How did you become a capitalist, then?

Mashaba: People must be careful by what they mean by capitalist. Capitalism for me is my right to feed myself and my family, to provide for myself and my family without any government intervention.

Government's role is to ensure that people don't kill me; when I have a dispute with you, to have courts I can take you to; and to provide infrastructure. That's the role of government. But I don't think I need any government to tell me that I must wake up to feed my family. If I decide that I don't want to work, why should government force me to work? As long as I'm not going to be a liability to that government. If you decide you don't want to work, then you cannot expect other people to assist you.

Obviously, some people for some reason need short-term intervention. I am for that. But if someone decides, "You know what, I don't want to work"? I don't think any government needs to force people to work. I don't need government to tell me I must work for you and then determine how much you must pay me and how many hours I must work.

When they start coming out with those policies, it is when you start stifling development. I've seen trade unions in this country becoming powerful and controlling our people. I was no longer allowed to reward people who are hard-working because unions assume everyone is the same. Unions discourage people from being the best they can be. I must pay people exactly the same regardless of whether they work hard.

People are under the impression that capitalism is about exploitation. In 1980, when I decided that I have to work, I worked for [the retail chain] Spar earning 1,875 rands a month (about $150). If Spar thought they exploited me, they made a terrible mistake. Was I happy with that R1,875? Absolutely not. I hated it. But I was so grateful for the opportunity. For me, I exploited them, because they didn't know what my agenda was. I needed experience. So with that R1,875, they paid me to train me! Never in the seven months I worked for them did I ask them for a raise. There was no need, because I was moving when I could find someone who would pay for experience.

They never wanted to give me a raise until the day I gave them my resignation letter. And then they started wanting to match the money the other company offered. It was too late. My life wasn't determined by Spar. I was in charge, and I said, "No, thank you very much," and I moved on and worked for Motale industries for 23 months, and I used the same approach.

You can check with everyone I've worked for: I put my heart into it. Not for them! I would like to encourage youngsters and others: Don't work for others. Work for yourself. Because I'm telling you no employer will want to lose a good working person.

reason: You've said that it's harder to start a new business under the ANC than it was under apartheid.

Mashaba: Because ANC operates on a basis of political patronage. They've destroyed black talent. They've destroyed black initiative. If you're not part of their inner circle you have no chance.

reason: What are your priorities? What are the metrics by which your tenure will be judged as a success or a failure?

Mashaba: Unemployment is an easy one that society can attack.

reason: But as mayor you can't, for example, change the labor laws. So your hands are tied.

Mashaba: No, I can't, but as a mayor of a powerful city like this I will keep on bringing unemployment into the public discourse, so people will understand the impact it is having on our economy.

reason: One of the things that I am hoping you will talk your colleagues into doing is to suspend all the zoning laws in the black areas until they have properly done planning schemes.

Mashaba: Well, did you see today? I'm only 23 days in office, and I did something the ANC could not do in 22 years.

reason: Under apartheid, white people had land ownership and black people lived on government land. That legacy endures, but you've given some title deeds, yeah?

Mashaba: Today! With EFF and IFP [the more conservative, Zulu-dominated Inkatha Freedom Party]!

You have to meet Mrs. Dikgale. She has lived in this house since 1963. She applied in 2007 with the ANC government, and after two years she gave up, because it was just costing her money running around. And 23 days later, here is it. I've got 2,000 title deeds that I've given officials to give to our people.

Tomorrow I'm hosting property developers in the city because I want to work with them. All these empty buildings in the inner city hijacked by the criminal elements. I'm saying to the criminal elements, please run away before I come, because I am going to work with those guys to make sure we evict you. I want to get civil society behind me.

reason: One of the things the council you now run was vicious about under the ANC was getting rid of street traders. Clearing them away as if they're litter. Literally: The litter department was given the job of getting rid of people. That's one of the biggest sources of unemployment for unskilled people—desperate, single people. What is your policy on that?

Mashaba: These poor people that you see that are selling on the street corners. Do you think they like that life? The ANC government has not made it possible for them to work in proper factories and shops, because the ANC hates business and hates profits. So what happens? Everyone has to sell potatoes and tomatoes on the side of the road. But if private-sector business is allowed to operate, why must people sell potatoes or whatever on the side of the road and make 20 rands (about $1.50) a day, when I can work in factory for 4,000 rands a month and get the experience?

reason: Do you have any quantified targets?

Mashaba: Unemployment in our city right now sits at 31 to 32 percent. It's very high. We need to drive this down and I am saying I'm committing to drive it to under 20 percent during my five-year term. If I fail, I want people not to vote me back, because they will know I've failed them.

Unemployment has reached crisis proportions in our country, and that's really what I want to put my emphasis on. Yes, I am talking about building houses and so forth, but I won't be able to build houses and infrastructure if I don't have the money, and where will the money come from? That is why I want to drive business.

reason: When you walked into the office and became a member, no one in the D.A. even knew you. You had no particular political ambitions. A year later, you are the mayor of the most important city in Africa.

Mashaba: Not a single political analyst or commentator gave me a chance. They wrote me off.

reason: What did they call you? Naive?

Mashaba: Naive and a novice. So no one believed. I actually thought we would get an outright majority. But even when I asked for an outright majority, I kept saying to the voters, "Please don't give me a blank check. You have been abused so long. You should not allow it."

Leon Louw is executive director of the South Africa-based Free Market Foundation.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Meet Johannesburg's New Libertarian Mayor."

Show Comments (283)