The System is Rigged: Licensing Limits the Pursuit of Happiness

Onerous licensing laws make it harder for people to move from place to place. And less residential mobility means less economic mobility.

Americans have always taken the idea of "the pursuit of happiness" rather literally. From east to west, south to north and back again, each generation tends to reshape the country by moving from place to place in search of better things.

Though it hasn't attracted as much attention as overblown fears about declining economic mobility, residential mobility—how easy or hard it is for someone to move from place to place in pursuit of better economic conditions—is on the decline. That matters, because when it's harder for people to move where the jobs are, it's also harder for them to move up the economic ladder.

That's the premise of a new paper by Scott Winship, a senior fellow with the Manhattan Institute. Winship argues that licensing and other regulations, like zoning laws, make it harder than ever for workers to move from one state to another in pursuit of better jobs.

"There is a widespread belief that Americans' economic mobility has declined and that Americans are also less likely to 'move to opportunity' than in the past," says Winship. "These two assertions have been linked to argue that falling residential mobility is an important factor behind diminished economic opportunity in America."

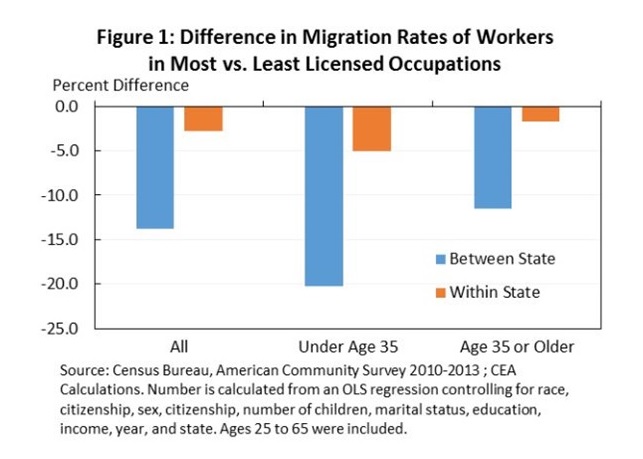

There's no doubt that states with higher licensing burdens see lower migration rates. In a wide-ranging report released last year on the consequences of licensing, the Brookings Institution identified a gap in migration rates between states with high licensing burdens and those with lower licensing burdens.

There could be any number of reasons for that beyond licensing—certainly there's a wide range of reasons why people would leave one state for another. ??'s study attempts to prove a causal link between those two things, essentially showing that declining residential mobility is causing declining economic mobility.

Most licenses aren't transferrable between states, so even though there might be a wealth of opportunities for interior designers in Washington, D.C., potential workers might think twice about moving there because they'd have to take 2,000 hours worth of classes and pass an exam before they can get a job.

More than one-third of all jobs in the United States is now subject to some form of licensing (up from just one in 10 jobs in 1970, acording to research by Morris Kleiner at the University of Minnesota), so more workers than ever before are forced to take their licenses into consideration when thinking about a move.

Ilya Somin, a law professor at George Mason University, laments that neither major party is discussion these serious issues. In a column at USA Today, Somin notes that the need to reform licensing laws is generally agreed upon by academics on all sides of the political spectrum, but still hasn't caught on with lawmakers—to the detriment of middle and lower income workers.

"In many cases, lower-income workers cannot move to practice their professions in a new state because of the new to meet burdensome licensing requirements," Somin writes. "Interest groups lobby to ensure that state licensing regimes make it difficult for competitors to come in from other states."

In short, the system is rigged against newcomers.

If Donald Trump were running anything like a competent campaign, this might be something that he'd have mentioned a few times by now. The notion that bureaucrats in Washington, D.C., and state capitals have creating licensing schemes that make it harder for workers to find jobs, harder for them to change jobs and driven up the price of basic household goods would square nicely with the anti-establishment, blame-the-politicians-for-this-fine-mess narrative he's been pushing for more than a year.

By now it's clear that he's more interested in stoking the flames of nationalism by blaming America's economic problems on immigrants, China and international schemes to move jobs out of the country.

For her part, Hillary Clinton has paid lip service to the idea that excessive licensing is bad for the economy, but it's hardly been a central theme of her campaign. As I wrote previously, she's mostly just promising to continue the (laudable) efforts of the Obama administration to make states pay more attention to this issue. She's also promising to spend tax money to effectively bribe states and cities into changing their licensing laws, which is a questionable strategy at best.

I doubt we'll hear anything about this issue during tonight's third and final presidential debate, but here's to hoping we do.