Dallas Photographer Busted for Taking Pictures in Public Files First Amendment Suit

"There is freedom of the press," observed a puzzled paramedic who witnessed the arrest.

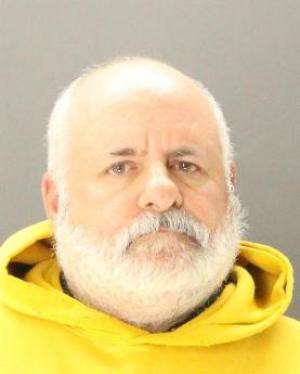

Avi Adelman, a freelance photographer in Dallas, was taking pictures at a Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) station last February when Stephanie Branch, a DART police officer, decided to arrest him for doing his job. The incident, described in a federal lawsuit that Adelman filed this month, shows how the First Amendment right to record images in public places can be both widely recognized and routinely violated.

Listening to his police scanner on the evening of February 9, Adelman heard a report of an overdose involving the synthetic marijuana substitute known as K2 at DART's Rosa Parks Plaza station and headed there, thinking the incident might be newsworthy. When Adelman arrived at the station, he saw Dallas Fire/Rescue (DFR) paramedics attending to a man lying on the ground and began to photograph the scene. Branch approached him and ordered him to stop taking pictures. Adelman noted that he had a constitutional right to photograph public events as long as he did not interfere with police or other emergency responders. Branch then demanded that he leave the area, and when he refused she grabbed him and handcuffed him.

While this was going on, a DART recorder captured revealing remarks by two paramedics and Elmar Lee Cannon, one of Branch's fellow DART officers:

First Paramedic: He was just taking pictures, right?

Cannon: Yeah. That's why I don't know why she's giving him a hard time.

First Paramedic: Why is she going crazy?

Cannon: I don't know. That's going to be on her. He can take all the pictures he wants. That's why I'm not getting involved in that…

First Paramedic: He knows he wasn't doing nothing wrong, so…

Cannon: I don't know why she's giving him a hard time…I don't know why she…There was no need for that.

Second Paramedic: Yeah. I don't know where that idea came from…because there is freedom of the press.

Branch nevertheless arrested Adelman for trespassing, and he spent the night in jail before posting a bond the next morning. Even though Branch was clearly in the wrong, as her colleague and the paramedics recognized, DART initially defended her. The day after the arrest, DART spokesman Morgan Lyons told the Dallas Observer's Eric Nicholson the agency had "reviewed the exchange and believes the officers acted appropriately." According to Lyons, "Dallas Fire-Rescue asked [Adelman] to move. He refused. Paramedics asked us to ask him to move several times. He failed to comply and that's why he was arrested."

That was not true, as became clear a few days later, when DFR spokesman Jason Evans contradicted DART's account. "At no point were any requests made to ask Mr. Adelman to leave the scene and/or stop taking pictures," Evans said. "In addition, there were no requests made to [DART] officers to ask him to leave the scene and/or stop taking pictures."

A few days after Branch's lie was revealed, DART informed Adelman that the charge against him had been dropped because the arrest was "not consistent with DART Police policies and directives." The agency launched an internal investigation of the incident, which concluded that Branch "did not establish Probable Cause to effect the arrest," since Adelman was "simply taking photographs of a person in a public place." The report from the DART Police Office of Professional Standards (OPS), which DART released six months after the arrest, noted that "Adelman was not breaking any laws," that surveillance video showed he was never less than 10 feet from "the actual medical scene" (vs. the "3 or 6 feet" that Branch claimed), and that the paramedics and the two other DART officers at the scene "did not witness Adelman ever interfere with medical treatment or medical personnel."

OPS found that Branch initially approached Adelman based on her "mistaken belief" that photographing the overdose victim was illegal under the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Adelman says he told her that HIPAA's privacy provisions do not prohibit photographs of medical treatment in a public place, but that did not placate her. OPS found that Branch's report on the incident included "various inconsistent, unverifiable or uncorroborated statements," including the whopper about the paramedics' supposed request that Adelman move back. In addition to DFR's unambiguous denial of Branch's account, OPS noted that no such request or complaint can be heard in any of the audio recorded at the scene. OPS identified more than 20 statements in Branch's report that were "not accurate." The report concluded that in arresting Adelman without probable cause, Branch violated DART policy and "engage[d] in conduct which was illegal or could reflect negatively on DART."

Adelman says DART never apologized to him for his false arrest and "refused even to discuss a resolution of this matter." He does not know whether Branch faced any disciplinary action, and he is concerned that DART's police force does not properly train its officers to respect First Amendment rights. OPS said Branch violated "DART's Photography Policy," which says "persons may take photographic or video images" as long as they do not "interfere with public safety activity." But Branch said she had never seen that policy. Furthermore, Adelman says, another DART policy could be interpreted as authorizing arrests of people taking pictures in the DART system. That policy says a criminal trespass charge is appropriate when a "person is on DART's property for purposes other than to utilize public transportation services."

Adelman, an activist and blogger who developed a "Right to Photograph and Record in Public" program for police officers, argues that DART's trespass policy "is unconstitutional because it permits DART police officers to arrest individuals for exercising their First Amendment rights at DART transit centers." In the first seven months of this year, he notes, "DART made 254 arrests for criminal trespass" and "presumably issued numerous additional criminal trespass warnings pursuant to its policy." He says the conflict between the trespass policy and the photography policy is apparent from the fact that a DART sergeant approved his arrest and a DART spokesman defended it. The sergeant, Homer Hutchins, told OPS he approved the arrest based on Branch's (false) report that Adelman was "getting in between the paramedics" and "preventing them from doing their job." The spokesman, Lyons, likewise relied on Branch's self-serving, inaccurate account.

In addition to unspecified compensatory and punitive damages for the violation of his constitutional rights, Adelman is seeking an injunction prohibiting DART from "arresting, detaining, warning, obstructing, or otherwise interfering with journalists and members of the public who are engaged in photographing or recording police or medical personnel at DART stations and transit centers." He also wants DART to "develop and implement comprehensive and effective policies to protect the First Amendment rights of the public and the press to observe, photograph, and record police or medical personnel on DART property, including appropriate training for DART police officers and supervisors and appropriate discipline for those who violate the policy."

Show Comments (69)