Freed at Last

Three stories of justice delayed

Their accounts begin differently but end in the same place. Antoinette Frink was the owner of an auto dealership in Ohio; she sold a dozen vehicles to customers who were in the business of distributing cocaine. Luis Rivera, a former pilot and Army National Guardsman, began smuggling drugs from Colombia into the United States in his 20s. Barbra Scrivner was a young mother whose husband sold crystal meth.

All three are nonviolent offenders who were sentenced to decades in federal prison in the 1980s, when our national anxieties about crime took a viciously punitive turn. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act, passed in 1986, stripped judges of discretion to decide on the particulars of a case how much time a person truly deserved, instead introducing mandatory minimum sentencing. The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act that Bill Clinton signed in 1994 ratcheted up the length of those sentences and funded a spree of prison construction to contain an unprecedented rise in the incarcerated population.

Today, violent crime rates in America sit at record lows, yet thousands of nonviolent offenders—with stories just like those of Rivera, Scrivner, and Frink—continue to waste their lives behind bars. But in these three cases, the tale eventually took a happy turn. As Americans and their leaders increasingly begin to question whether tough-on-crime policies are worth the monetary and human costs, some people are finally being given second chances.

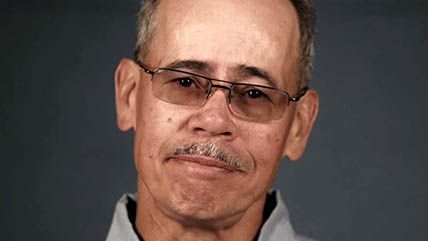

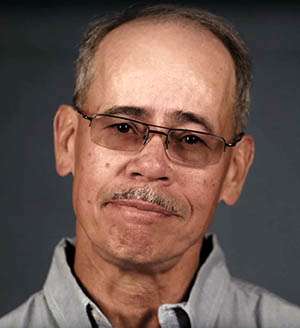

Luis Rivera might have died in prison. For the crime of transporting cocaine across the border, Judge Frank Seay sentenced him in 1985 to life without parole plus 140 years. "Rehabilitation appears hopeless for a person of your experience and knowledge," Seay declared at the time. "My intent is that you spend the rest of your life in federal institutions."

The Holloway Doctrine states that even after every legal appeal has been exhausted, courts may still reduce a sentence that is disproportionately severe. There was reason to believe from the beginning that this sentence was: "After [the judge] slapped the gavel and left, all the other lawyers got up and walked over to where we were and said, 'Hey, that's ridiculous. He can't do that,'" Rivera recalls.

Three decades later Seay came to agree. In a rare reversal, the same judge who handed down the initial sentence granted Rivera's immediate release last year. He is free and rebuilding his life in Florida, with dreams of becoming a helicopter pilot.

Barbra Scrivner's third plea for clemency was the charm. She credits Families Against Mandatory Minimums for publicizing the injustice of her sentence and bringing her plight to the attention of the federal government.

Important to her case was the fact that it was her husband, not her, who was cooking and distributing methamphetamines—and the courts knew it. "The jury found me guilty of conspiracy," she says. "I guess in their eyes they believed that I knew what was going on. Doesn't matter…if I wasn't no part of it and it didn't have anything to do with me. Being found guilty of conspiracy, that charge makes you liable for every single thing that anybody ever did."

After 20 years, 11 months, and three days in prison, Scrivner's sentence was commuted by President Barack Obama in 2015.

Antoinette Frink was also convicted on conspiracy charges, and spent more than 11 years in prison on a sentence of 188 months. She too fell prey to the contention that she "knew or should have known" that other people were engaged in illegal activities—in this case, using cars she had sold them to deal drugs. "I thought it was sort of ludicrous," she says. "I didn't think I would be indicted for that. This is something that will blow over and I'll be cleared. But that was the farthest thing from the truth."

Frink's travails were all over the local news: "I was the headline—I was the automobile dealer, which was something unusual, especially as a female, in the '80s." But although the media speculated that she could receive 30 years or even a life sentence, she says she didn't realize the severity of the situation at first. "I had no idea of what any of that meant until I got to prison," she says. "And that's when it really sunk in."

Frink's sentence was eventually commuted by Bill Clinton in 2000—one of his final acts in office—after former President Jimmy Carter weighed in on her behalf. The day her sister confirmed she was indeed on the commutation list, she says, "I just started crying." Today, Frink is a practicing tax preparer in Georgia.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Freed at Last."

Show Comments (1)