Justice Kennedy to Government Lawyer: 'You're Asking Us to Make It a Crime to Exercise What Many People Think Of As a Constitutional Right'

SCOTUS hears arguments in Birchfield v. North Dakota.

This week the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Birchfield v. North Dakota, an important case that pits the Fourth Amendment right to be free from warrantless government searches against the government's desire to impose warrantless DUI tests on suspected drunk drivers. At issue are state laws from North Dakota and Minnesota that make it a crime for a suspected drunk driver to refuse to submit to a warrantless breath or blood test. The specific legal question before the Court is, "Whether, in the absence of a warrant, a State may make it a crime for a person to refuse to take a chemical test to detect the presence of alcohol in the person's blood?"

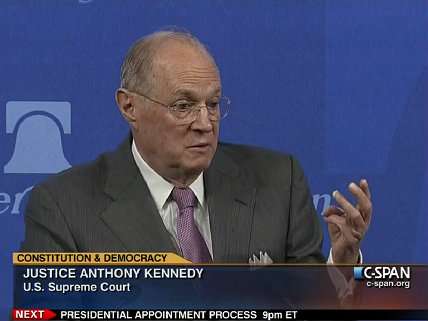

Multiple justices expressed doubts about the constitutionality of the actions taken by North Dakota and Minnesota. "You're asking for an extraordinary exception here," Justice Anthony Kennedy told Thomas McCarthy, the lawyer representing North Dakota. "You're asking for us to make it a crime to exercise what many people think of as a constitutional right," meaning the right to say no to a warrantless government search. "There is some circularity there," Kennedy noted. "And you could point to no case which allows that."

"If you're taking them to the police station anyway to do the breath test, and it just requires a phone call to get the warrant, what's the problem?" Justice Stephen Breyer queried Kathryn Keena, the lawyer for Minnesota, who had just explained that the only breath test results that are admissible in court are the ones that are conducted at the police station after the suspect is arrested. "Why can't you just call the magistrate, and at least we have some kind of safeguard against total arbitrary behavior."

Charles Rothfeld, the lawyer representing Danny Birchfield and the two other petitioners challenging the state laws, faced his sharpest interrogation on the question of whether the Court should treat warrantless breath tests differently than it treats warrantless blood tests. This line of questioning centered on the idea that breath tests really aren't that invasive and may perhaps be constitutional as part of the valid search that police may conduct without a warrant incident to a suspect's arrest.

"It's an intrusion when you pat down someone having probable cause to believe he's committing a crime," observed Justice Breyer, "Pat-down is a much more intrusive form of search than saying would you blow into a straw." In other words, Breyer asked, if the Court permits the police to pat-down suspects without a warrant, why shouldn't the Court permit the police to tell suspects to "blow into a straw" without a warrant?

Justice Elena Kagan made a similar point. "There are searches and then, again, there are searches. There are more invasive searches and less invasive searches." Perhaps the less invasive breath test should be judged under a more lenient standard than the far more invasive blood test, which requires a trip to the hospital, she seemed to suggest.

Judging by the oral arguments, it seems conceivable that the Supreme Court will void the state refusal laws that govern warrantless blood tests while at the same time allow the states to maintain their criminal sanctions against suspects who refuse to submit to warrantless breath tests.

A decision in Birchfield v. North Dakota is expected by June.

Show Comments (85)