Policing Students' Sex Lives Costs Colleges Millions, But Nobody's Happy With Results

When stopping sex discrimination requires more sex discrimination, how can anyone win?

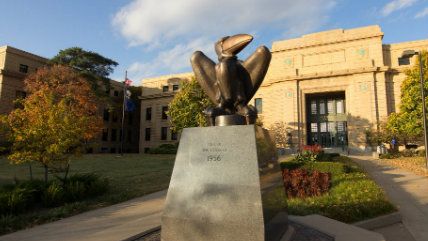

In order to fall into compliance with federal anti-discrimination law, the University of Kansas (KU) should segregate male student athletes to special dorms and immediately suspend anyone accused of sexual assault, argue the lawyers of a former student who says she was raped in the KU dorms. The young woman, Daisy Tackett (who has chosen to be public with her name and identity), is now suing the university in federal court.

According to Tackett's claim, the school's failure to take reasonable steps to prevent the assault and to adequately address the situation afterward created a "hostile" educational environment, in violation of the federal statute known as Title IX. The original aim of Title IX was to combat institutional sex discrimination in education, but it has since morphed into "a lever by which the federal bureaucracy monitors schools' policies and procedures regulating sexual behavior," as Harvard law professors recently put it. These days, schools are increasingly finding themselves under investigation by the Education Department's Office for Civil Rights (OCR) and on the receiving end of student lawsuits over perceived inadequacies in addressing sexual harassment and assault on campus.

Tackett's lawsuit against KU epitomizes the shortcomings of this system. But that isn't a condemnation of Tackett nor her parents, who have also filed their own suit against KU under Kansas consumer protection law. Tackett has provided no reason to disbelieve her accusations against "John Doe G," a fellow student and member of the KU football team who was expelled from KU this March. It's understandable for Tackett and her family to feel upset, betrayed, or whatever emotions are motivating their current actions. And while I think the Title IX lawsiut is misguided, I'm not here to judge or express scorn toward people trying to handle a tough situation in the best way they see available. No, the problem is with the options and incentives that are available to begin with.

This piece is not about calling out vulnerable people for failing to react perfectly. It's about the Title IX takeover of U.S. universities and its wide-reaching detrimental effects.

Daisy's Story

On Halloween night of her freshman year, Daisy Tackett and her friends wound up at a post-party gathering at the Jayhawker Towers, an upperclassmen residence hall on the KU campus. According to Tackett's lawsuit, John Doe G—who also lived in Jayhawker Towers—showed up at that gathering and "appeared inebriated." Eventually, Doe invited Tackett back to his room "to watch a television show and then sexually assaulted her." Tackett "remained in his apartment in a state of shock and horror until John Doe G said he needed to leave in the morning for football practice," the lawsuit states.

Tackett "chose not to report the sexual assault at the time, although she did confide in a teammate" on the school's rowing team, according to the suit. Around a year later, in October 2015, another woman on the school's rowing team with Tackett confided that she, too, had been sexually assaulted by Doe, and had reported it to the school and the police. That's when Tackett decided to come forward. Initially confiding to a rowing-team trainer, Tackett eventually reported Doe to KU's Institutional Opportunity and Access (IOA) Office, which opened an investigation.

After the IOA meeting, Tackett "was departing class at Blake Hall on the KU campus, a low-traffic area of campus, when she encountered John Doe G, whom she had never seen at that time and location of campus, staring her down," the lawsuit states. Later that week, she saw Doe in front of the library, where he "stared her down and called her a derogatory name." Tackett reported both events to the IOA office, which assigned an escort to walk her between Blake Hall and her next class.

Around this same time, Tackett started having "panic attacks and anxiety," especially when rowing workouts were held in or near the football stadium. In November, her rowing coach said she couldn't attend an upcoming training trip to Florida, which he later claimed was because she had skipped workouts. But Tackett alleges that the coach—who had a history of what some team members viewed as problematic comments about their weight—excluded her from the trip in retaliation for speaking up about the coach's commentary and with disregard for the reason why Tackett was skipping workouts. Soon thereafter, Tackett "reported Coach Cathloth's retaliation against her" to the IOA.

After returning from winter break in January 2016, Tackett remained in school for one week before dropping out and moving back home to Florida. In March, Doe was expelled from KU.

Catch IX

In a statement, Tackett's lawyers claim that the University of Kansas created "a hostile educational environment when it chose to house KU football players in the Jayhawker Towers, despite knowledge of a high rate of sexual assaults." Further, the school "had reason to know she might be retaliated against, but … failed to protect her from retaliation by the KU football player."

Tackett's lawsuit accuses KU of knowing "that sexual assaults were occurring at a high rate at Jayhawker Towers" and yet failing "to provide adequate supervision, warnings, training guidance, and education to its athletes and KU football players in particular." The "likelihood of such misconduct was so obvious that KU's failure to supervise amounted to deliberate indifference to the rights of Daisy Tackett," it states. The suit further alleges that implementing a few "simple, reasonable policies" could have "lessen(ed) the chance of rapes occuring, harassment occuring, or retaliation occuring." Yet KU "failed to immediately issue a 'no contact' order to John Doe G after receiving two independent reports of sexual assaults involving him," "failed to immediately suspend John Doe G pending the outcome of KU's investigation," and "failed to ban John Doe G from campus pending the outcome of KU's investigations."

Putting aside for a moment whether these claims are reasonable, let's look at what Tackett's lawyers think the school must do to be compliant with Title IX, the law that says schools can't discriminate on the basis of sex. First, they assert that KU should single out one class of students—male athletes—for special, segregated housing and anti-rape training. But of course, this itself could be a violation of Title IX. Tackett's lawyers also say that in order to create a safe and non-discriminatory educational environment for victims, students should be suspended from school and banned from campus upon any accusation of a sexual assault. But not only would this seriously violate the rights of anyone accused, it could also open the school up to yet more Title IX lawsuits.

Accused students who feel they have received an unfair shake from campus administrators during sexual-misconduct hearings have begun realizing that they, too, can use Title IX to their advantage. A slew of recent cases pits colleges against male students who say that they were the real victims of sex discrimination in their cases, and some have already won.

But universities can't win, not with the hand they've been dealt by the Office for Civil Rights. Inevitably, the interests of opposing parties in cases of sexual-misconduct—a category broad enough to include rape and offensive comments—are going to conflict to some degree, and striking the right balance between the rights of both parties isn't easy under any circumstances. Now schools also face the prospect of losing all direct and indirect federal funding and spending hundreds of thousands of dollars fighting lawsuits because OCR has defined missteps made by schools in individual misconduct complaints as institutionalized sex discrimination. Any student—accuser or accused—who doesn't like the way things play out can now re-litigate the matter in federal court.

Campus Housing "Obviously Not Safe"

The things Tackett's lawyers ask of KU in the name of Title IX compliance are simply not reasonable from a legal standpoint. But that's not their only flaw. What makes these requests especially ridiculous is that they're not rooted in the reality of rape on the KU campus, nor would they adequately prevent sexual assaults like what Daisy Tackett describes.

Tackett's claims hinge in large part on the idea that "sexual assaults were occurring at a high rate at Jayhawker Towers." And yet the lawsuit pinpoints just one incident of sexual assault and three incidents of sexual battery (defined as "unwelcome contact with or touching of another person's genitals, breasts, buttocks, or other unwelcome physical contact of a sexual nature) at the dorm building from 2013 through early 2016.

According to KU crime report data, the school received 14 reports of on-campus rape in 2014, with 10 occurring in residential facilities. Ten forced fondling incidents were reported that year. With around 25,000 students attending KU's main campus, that means that around 0.096 percent of students each year will report being sexually assaulted in some way while on the KU campus and around 0.005 percent will report being sexually assaulted at the Jayhawker Towers.

Crime data from previous years show similarly low levels of sexual assault reports. In 2013, a total of 13 on-campus sex offenses were reported, including nine that occurred in residence halls. In 2012, three on-campus incidents were reported. In 2011, there were two and in 2010 there were five. Obviously not all victims will report incidents, so these numbers don't necessarily reflect the full scope of sexual assault at KU. But they also highlight the absurdity of claiming that the likelihood of Tackett being raped in Jayhawker Towers was "so obvious" that KU was somehow negligent in not preventing it. And they add a hollow ring to the advice from Tackett's dad about how other parents can protect their kids at KU: "Move them out of the housing because it is obviously not safe."

And yet, some 1.3 assaults per year were reported as occuring at Jayhawker Towers. Are there "simple, reasonable" steps the university is forgoing that could be contributing? Tackett's lawyers say yes: the school failed to provide adequate security at Jayhawker Towers and adequate "warnings, training guidance, and education" to students about prohibited conduct and personal risk.

The claims are dubious. Jayhawker Towers is one of at least 25 dorms on KU's main campus (which also includes 14 sex-segregated dorms). It's a coed dorm for upperclassmen, transfer, and nontraditional students, with about 200 suites and a wait-list to get in for the 2016-2017 year. A key is required to enter the building 24 hours per day, and security cameras can be found around all entrances and exits. Resident assistants and other staff are in the building at all times, and campus safety officers make nighttime rounds.

In a residential life handbook, KU instructs student residents that they are beholden to all local, state, and federal laws and university policies and regulations and reminds them that "residents should be mindful of personal safety." It defines offenses including sexual assault, rape, sexual battery, and sexual harassment, states clearly that these are prohibited, and reiterates that KU is "committed to preventing, correcting, and disciplining incidents of unlawful harassment, including sexual harassment and sexual assault." It has reported student sexual-assault data years before the federal government required it and has a number of programs dedicated to training students, staff, and professors about sexual harassment and assault.

Risk and Retribution

External security features like those at Jayhawker Towers make little difference when it comes to the vast majority of campus rapes, which aren't a matter of nefarious strangers getting into student residence halls but happen between students who willingly enter one another's dorm rooms. Such was the case with Tackett and Doe. And short of enforcing a total ban on students entering each other's rooms, I'm not sure how KU could preemptively thwart these sorts of assaults.

Throughout Tackett's lawsuit, it is alleged that KU football players were housed in Jayhawker Towers because it has less strict rules and security than do some other residence halls. Yet, presumably, none of the dorms are so strict as to totally prohibit students from inviting another student in (and enforcing this ban). So how would housing Doe (or all male athletes) in a different dorm have prevented him from inviting Tackett to his room? Or her from accepting the invitation? By Tackett's own account, Doe was the one who was "inebriated," not her, and she went with Doe to his room of her own accord.

There's no reason to fault Tackett for that decision, or to assume that it relieves Doe of some responsibility. People should obviously be able to enter private spaces with other individuals—to watch TV or whatever else—and maintain an expectation of bodily autonomy. The bulk of dating is based on placing this trust in one another. But people do violate this trust sometimes. Sadly, Tackett (and many others) have to learn this or the first time at a point in their lives when they're already confused and vulnerable, having just entered college and started coping with a lack of parental restrictions and an influx of personal responsibility for the first time.

The small but real risk in being behind closed doors with someone you barely know is not one that can be collectively dealt with, however. Short of some sort of constant surveillance from authorities, there's just no way a third party can preempt sexual assaults of this nature. What we can do, however, is hope that perpetrators of violence will be held accountable and victims find some measure of retribution in the criminal justice system.

Yet with the extra-legal justice system encouraged by Title IX, students are instructed and incentivized not to go to police with rape or sexual battery claims. Police are bad at handling rape, young women are told, and thus it's better to appeal to campus administrators. There is no "right" response to being raped, advocates argue, and thus no imperative to even discuss with vulnerable populations (like college women) how their post-assault actions might matter. We need to believe and support victims, which means not burdening them with things like statutes of limitations for bringing criminal charges or biased questions about why they wait to come forward.

Who are we helping with this all or nothing attitude? While it may not be ideal, there's no getting around the fact that certain steps—preserving DNA evidence, getting a medical examination post-assault, reporting the matter to authorities in a timely manner—can go a long way toward successful prosecution. This sort of officialized justice may not be important to all victims. And these steps won't guarantee success. But if we're serious about reducing sexual violence, one of the best ways is by reducing the population of sexually violent people who go unpunished. And this requires not just creating a safe space for victims to speak up (something campus/women's groups have been good at fostering) but creating the conditions where arrest, prosecution, and conviction are actually possible.

Promoting greater compassion and less victim-blaming in sexual assault situations isn't at odds with empowering people to know their options and act accordingly if they are victimized. What we can't continue doing is pretending that a victims' actions don't matter in any way. From a moral perspective, that might be true, but it's simply not true from a practical or legal perspective, and we fail future victims when we don't acknowledge that.

The Cost for Colleges and Students

In encouraging students to seek recourse not from cops and courtrooms but from Title IX coordinators and settlements, we've set up a system that doesn't seem to bring either security or justice for sexual assault victims, violates the rights of the accused, and fails to punish the guilty in a way that might prevent future assaults. It also ends up consuming a lot of university resources. At a time when everyone's worried about inflating college costs, this ought to give people pause. The New York Times recently reported that between hiring Title IX lawyers, investigators, peer counselors, victims' advocates, case workers, etc., colleges have been spending millions of dollars addressing sexual misconduct complaints.

"Title IX coordinators … can earn $50,000 to $150,000 a year," according to the Times. The estimated cost of "lawyers, counselors, information campaigns and training to fight sexual misconduct ranges from $25,000 a year at a small college to $500,000 and up at larger or wealthier institutions."

The University of California, Berkeley has increased Title IX spending by at least $2 million since 2013, officials there said. The University of Oregon recently authorized $500,000 in new spending to hire additional Title IX staff.

School lawyers are tasked with defending colleges against both federal government investigations—210 and counting, up from 55 just two years ago—and a growing number of student lawsuits claiming sex discrimination. This is expensive and time consuming even when a university wins. "There's so much more litigation on all sides of the issue," Brett Sokolow, executive director of the Association of Title IX Administrators (founded in 2011), told the Times. "This has very much created a cottage industry." Responding to a lawsuit "can run into the high six or even seven figures, not counting a settlement or verdict," Sokolow said.

Wade Robinson, KU's vice president for campus life and university relations, told KWCH 12 last year that preventing and punishing campus sexual assault is a topic that "dominates our time … through the conduct process and education process. This has exploded. This is the top issue at this point."

Wouldn't it be better for all parties if universities could go back to seeing students' education as their "top issue" and let sex crimes be handled by parties we specifically designate to handle criminals?

Alas, that doesn't seem likely any time soon. Senators are currently seeking an additional $138 million for federal investigations of campus sexual misconduct. The money would go to the Office for Civil Rights and the federal Clery Act Compliance Team, which handles campus crime-reporting data. The Clery team's complaints were up from 16 in 2012 to 87 complaints in 2015. OCR reports that Title IX complaints have skyrocketed from just a few in 2009 to 106 complaints in 2014 and 165 complaints last year.

Show Comments (183)