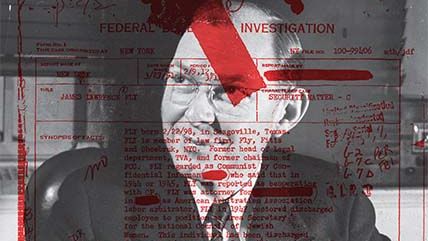

The Man J. Edgar Hoover Blamed for Pearl Harbor

Larry Fly, the forgotten hero who refused to illegally wiretap Americans

The accusation stunned wartime Washington. In July 1943, numerous newspaper columnists blamed one specific federal employee for the intelligence failures that led to Pearl Harbor. His name was James Lawrence "Larry" Fly, and he had been coordinating all civilian and military telecommunication since 1940. While chairing both the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the Defense Communications Board (DCB), Fly had accrued significant political enemies simply by fulfilling his responsibilities. With so many critics, the smear stuck.

Fly knew immediately who had planted the rumor. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover had secretly approached Fly in September 1940 with an urgent request. The bureau wanted permission (and access) from Fly's FCC to secretly wiretap various unnamed Americans and foreign nationals within the United States. Fly, who possessed a remarkable command of media law, knew Hoover's request violated not only the Fourth Amendment but Section 605 of the Communications Act of 1934. That section, titled "Unauthorized Publication or Use of Communications," contained a subsection called "Practices Prohibited" that clearly indicated warrantless wiretapping was illegal.

Fly rejected Hoover's request. Hoover never forgave him.

Indeed, Fly's refusal triggered an enmity so enormous, personal, and long-lasting that Hoover's biographer, Curt Gentry, described it as legendary even by Washington standards. Hoover pushed the Pearl Harbor accusation relentlessly for the rest of Fly's life, and Fly would battle Hoover's agency—in courtrooms, in the press, on television, and elsewhere—for decades. Yet few Americans today have heard of Larry Fly. His legacy of civil libertarianism and his courage in challenging the FBI remain largely forgotten in our amnesiac culture.

With every revelation about the expansion of illegal surveillance, and with each news report chronicling the decline of privacy protections, the civic cost of forgetting Fly's efforts continues to escalate. The post-9/11 debates over expanding the surveillance state would have unfolded very differently had Fly's crusade against illegal wiretapping been integrated in public school civics curricula. Indeed, in the years since 9/11 it is difficult if not impossible to locate a federal functionary of Fly's stature publicly campaigning against infringements of liberty. Fly was the rare politically appointed bureaucrat more loyal to the Constitution than to any specific administration or party.

Fly's biographer, Mickie Edwardson, died before completing her full manuscript. She did, however, publish several scholarly articles drawn from her research. Media historians, regulatory activists, and civil libertarians all remain indebted to her labor. Much of this article, for example, draws from Edwardson's "James Lawrence Fly, the FBI, and Wiretapping," published in The Historian in 1999.

But it's not simply the biographical void that explains Fly's disappearance. It's also the fact that few prominent figures in American political history acquired so many powerful enemies. At different times, over less than a decade, Fly was condemned by such powerful business and political leaders as CBS Chairman William S. Paley, RCA Chairman David Sarnoff, 1940 Republican presidential nominee Wendell Willkie, and of course Hoover. Only the patronage of President Franklin Roosevelt buoyed Fly in the stormy political waters of World War II Washington.

Roosevelt's Man

Fly's relationship with Roosevelt was complex. Though an ardent New Dealer and lifelong Democrat, Fly's regulatory and political positions often clashed with the administration. In addition to his quarrel with the FBI, Fly delayed (and ultimately side-tracked) an investigation Roosevelt had personally demanded into newspaper ownership of radio station licenses. He also skillfully sabotaged the president's ill-conceived plan to nationalize one of NBC's two radio networks immediately after Pearl Harbor. And when the White House pressured advertisers and networks to crack down on critical radio news commentary during the war, Fly publicly distanced himself from this shady unofficial censorship campaign. "It is a little strange," he told the press, "that all Americans are to enjoy free speech except radio commentators."

In another area, Fly may have been more regulatory than the president preferred. There is considerable evidence that he defied the White House when his FCC promulgated new rules limiting the power of the radio networks to restrain trade by imposing illegal contractual terms on their affiliates. These rules ultimately led to Fly's landmark Supreme Court victory in NBC v. United States (1943), which firmly established the supremacy of the FCC's authority over American broadcasting.

Despite the clashes, Roosevelt stood by his friend. In 1941, RCA Chairman David Sarnoff scheduled a personal meeting with FDR to request Fly's firing, but he got nowhere. "I will pay for the meal if you and Fly take lunch together and settle the argument [over television]," Roosevelt offered.

Why did Roosevelt continually back his FCC chair in the face of such intense pressure? Fly's background offers one explanation.

Born in 1898 to a poor but politically connected Texas family, Fly won appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy. He graduated in 1920, but a bout of tuberculosis cut short his military career. So he headed to Harvard Law School, where he became a protégé of future Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter. After a short stint at the New York law firm of White and Case, Fly joined Herbert Hoover's Justice Department, where his cases involved antitrust and restraint of trade issues; his legal renown grew when he spearheaded the successful prosecution of the sugar trust. After Roosevelt's election, Fly became counsel of the Tennessee Valley Authority, where he bested Wendell Willkie's Commonwealth & Southern Corp. in the Supreme Court. (Fly, Willkie told the press, was "the most dangerous man in America—to have on the other side.") In 1939, Roosevelt named Fly chairman of the FCC, where he immediately changed the agency's atmosphere and tone. Hearing rooms were remodeled to resemble courtrooms, and everyone was told to rise when the commissioners entered.

Like Roosevelt, Fly could be combative and authoritarian. But they shared more than temperamental traits; both possessed personal connections to Harvard, the Navy, and the Democratic Party. Roosevelt developed enormous confidence in his appointee, a trust that shocked the military when, on September 24, 1940, Roosevelt named Fly rather than a military man to run the newly created DCB. This board was given enormous administrative power to coordinate and regulate the entirety of American telecommunication. With war looming, Fly seemed a curious pick.

The Wiretapping War

Almost immediately, Fly was tested by J. Edgar Hoover's wiretap request. Once he rejected Hoover's demand, the FBI director turned to Capitol Hill. Hoover encouraged hearings beginning in early 1941 to alter the Communications Act and expand governmental surveillance authority. With war exploding around the globe, the proposed legislation looked sure to pass—until Fly testified. His testimony was offered in executive session, due to the risk that national security secrets might be divulged, so no precise transcript exists. But everyone in the room left impressed with Fly. "He blew that goddamn bill up to the ceiling," FCC attorney Joseph Rauh later recalled. "There wasn't anything left of the wiretapping bill when he got done with it."

Then Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Fly's job assumed new significance at precisely the same time that national security concerns severely restricted public discussion of policy. The tension between Hoover and Fly moved almost entirely out of public view until that summer morning in 1943 when newspapers reported Fly had obstructed Hoover's attempts to prevent Pearl Harbor. Columnists hinted that Fly not only was guilty of preventing the "interception" of Japanese messages, but had permitted Japanese-language broadcasting to continue in Hawaii against the advice of law enforcement and military authorities. Many newspaper accounts also charged Fly with keeping the FBI from procuring the FCC's collection of hundreds of thousands of fingerprints belonging to station operators.

We know today that the precise wiretapping demanded by Hoover in 1940 actually did happen in the end. But it was military intelligence officials, rather than the FBI, who intercepted and decoded messages between Japan and the United States. The Security Intelligence Section of U.S. Naval Communications famously intercepted communication directed to the Japanese embassy in Washington shortly before Pearl Harbor. On the evening of Saturday, December 6, 1941, Roosevelt was handed the final parts of a decoded message, and, after reading the note, looked across his desk at aide Harry Hopkins. "This means war," the president said.

We don't know how much Fly and Hoover knew of this military intelligence. But regardless of the reality, Hoover could not forego an opportunity for retribution. When the House established a special Select Committee to Investigate the Federal Communications Commission in early 1943, the FBI director seized his chance for vengeance. But Roosevelt foiled Hoover and rescued Fly by announcing that no testimony could be given that might damage national security or divulge military information. That order effectively silenced everyone who knew anything about Pearl Harbor—military intelligence, Hoover, and Fly. So Hoover, working closely with military sources embarrassed by the Pearl Harbor catastrophe, leaked the wiretapping story to the press. The president's gag order prevented anybody from either corroborating or disproving the rumor. When called before the Committee, Hoover followed orders and grudgingly declined to answer questions. But in response to an inquiry from Rep. Louis E. Miller (R–Mo.), Hoover let the Committee know that "if he were permitted to talk he could 'shed some light' on Pearl Harbor,'" Broadcasting reported.

Ultimately, the investigative committee came to naught, and in 1944 an exhausted Fly let Roosevelt know he wanted to resign. At the president's request he served through the election, but by the end of the year he had returned to the private sector.

But Fly wasn't through with the issues he had engaged while he worked for the government. In 1946, he accepted an invitation to become director of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and from that position he continued to fight warrantless wiretapping.

On to the ACLU

Knowing the extensive use of wiretapping in New York under Thomas Dewey, Fly publicly called on the U.S. attorney general to enforce Section 605 within the state's borders. He embarrassed the FBI in one famous case, involving a Justice Department employee named Judith Coplon accused of passing secrets to the Soviets. Much of the evidence against Coplon had been secured by warrantless wiretap, so Fly filed a motion to reveal not only the full content of the specific wiretaps but the scope and extent of all related wiretapping being done.

The supervising FBI agent, Robert J. Lamphere, explained the Bureau's resistance to compliance: "To release the basic file reports might not only endanger security and compromise informants but also bring to light many unsubstantiated allegations which would do no one any good." The court sided with Coplon, and some of those "unsubstantiated allegations"—for example, that actress Helen Hayes and actor Edward G. Robinson were either communists or helped the communist cause —were read into the record, much to the bureau's chagrin.

The FBI followed up by destroying much of the remaining evidence in an attempt to hide its activities. While the Coplon case wound through the courts, and the FBI looked increasingly suspicious, Fly explained the danger of illegal wiretapping in the pages of The Washington Post. He later published articles excoriating Hoover's wiretapping habit in The Saturday Review of Literature, going so far as to explain, in 1956, how the FBI director leveraged illegal information by threatening victims with exposure via cooperative newspaper columnists such as Walter Winchell. Although Coplon was eventually convicted, Fly emerged as the face of resistance to expansive wiretapping. He testified before Congress in 1953 and 1954, and he appeared on Edward R. Murrow's See It Now on December 1, 1953, where he debated wiretapping and surveillance legislation with Rep. Charles Halleck (R–Ind.).

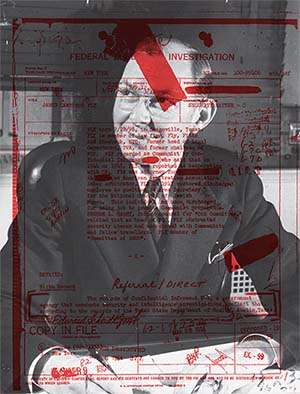

But Fly never fully outran the Pearl Harbor smear. His FBI file is filled with reports detailing inaccurate "facts" and scurrilous rumors. "FLY regarded as Communist by Confidential Informant [redacted] who said that in 1944 or 1945, FLY was reported as cooperating with CP [Communist Party]," offered one typical update. The FBI's defamation followed Fly even into retirement, when he led a group of applicants (the South Florida Television Corporation) attempting to secure a license to operate a television station in Miami, Florida. The FCC denied the application.

A Forgotten Hero

Even after National Security Agency (NSA) warrantless spying was revealed publicly in 2005, and even after Edward Snowden exposed massive governmental surveillance programs in 2013, the instructive example of Fly's battles with Hoover never registered in public debate. The consensus history skips almost directly from the Supreme Court's 1928 Olmstead decision legalizing warrantless wiretapping to the FBI's abuses in the 1960s and the Supreme Court's 1967 Katz decision, which reversed Olmstead by establishing that wiretapping violated a "reasonable expectation of privacy" standard. Paul Starr's widely lauded 2004 book The Creation of the Media: The Political Origins of Modern Communications, published shortly before the NSA wiretapping story broke, reads back American legal guarantees of private communication to the Post Office Act of 1792. "Lack of popular trust in the privacy of communications," Starr argues, is a hallmark of "closed or restricted regimes" that should be contrasted with America's more restrained and successful libertarian model.

A decade later, one could argue that "lack of popular trust in the privacy of communications" is the hallmark of a sophisticated and technically literate democratic political culture. But Starr was not simply a victim of bad timing; his naiveté about privacy stems from a deep-seated desire to believe in a specific kind of American exceptionalism. That distinctiveness is defined by a faith in the idea that—unlike those foreign countries with their endemic corruption—authorities representing the American government will follow the law when fulfilling their responsibilities.

James Lawrence Fly understood that such credulousness ultimately hurts the citizenry. If America is ever to engage in a serious and complex debate over surveillance and privacy, it needs to engage the history of both egregious trespass and civil libertarian resistance. Thanks to Snowden, that discussion is significantly more advanced than it was just five years ago. But we have a ways to go. We especially need to be wary of those defaming, exiling, or imprisoning Americans willing to risk everything to expose provable illegality committed by their government.

Meanwhile, Victor Pickard, Michael Stamm, and other media scholars are following Mickie Edwardson in rehabilitating Fly's reputation. As a result, more people are becoming aware of a career that, in Edwardson's words, "illustrates the hazards officials face when they take unpopular stands." Fly, she wrote, "suffered from newspaper columnists questioning his loyalty, from a federal board declaring him a hidden Communist, from congressional committees, and even difficulties with private business affairs. The punishment Fly suffered makes it easier to understand the silence of many public servants."

Fly didn't wish he'd been silent. In 1966, shortly before he died of cancer, he told his young grandchildren he had just one regret from his years in government: his "failure in teaching John Edgar Hoover the Bill of Rights."

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Man J. Edgar Hoover Blamed For Pearl Harbor."

Show Comments (17)