Friday A/V Club: The First Presidential Debate of the Broadcast Era

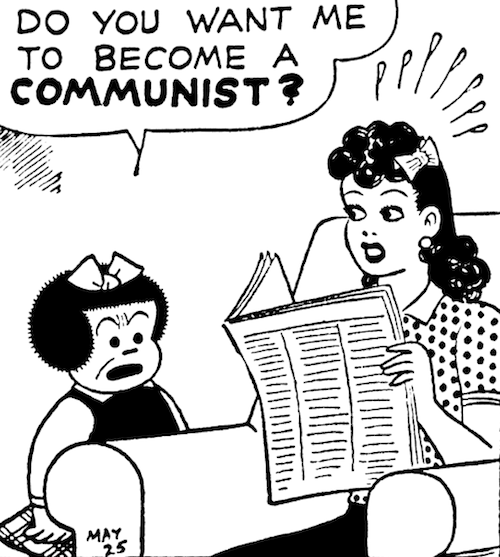

The central topic: Should the U.S. ban the Communist Party?

If you're sick of the Clinton/Sanders and Trump/Cruz/Rubio/Kasich debates, here's an alternative: the very first presidential debate to be broadcast in the United States. No, not one of the Kennedy/Nixon face-offs of 1960—those were the first televised debates. This was a radio program aired in 1948, pitting two Republicans against each other right before Oregon held the campaign's final primary. The candidates agreed in advance to focus on just one issue: whether the Communist Party should be outlawed.

The debate was held in Portland on May 17. The debaters were former Minnesota Gov. Harold Stassen, representing the liberal wing of the party, and New York Gov. Thomas Dewey, generally considered a moderate. (Several other candidates were running for the nomination as well, most notably Ohio Sen. Robert Taft—widely seen as the party's leading conservative, though he considered himself a liberal in the classical sense of the word. But only Stassen and Dewey were on the Oregon ballot.) The format didn't have much in common with the debates we're used to today: Stassen spent 20 minutes making his case, Dewey got the same amount of time to respond, they each issued brief rebuttals, and then it was over. Stassen tried to shoehorn several issues into his opening spiel, but Dewey didn't take the bait: After a wry reference to Stassen's "eloquent discussion of the subject, and of all the other matters which he brought up," he kept his attention on the topic at hand and Stassen followed suit.

Interestingly, it was Stassen, the liberal, who wanted to ban the Communist Party. "Such a law would not outlaw ideas," he insisted. "It would not outlaw thoughts. It would make illegal organized conspiracies of fifth columnists." Dewey retorted that organized conspiracies of fifth columnists were already illegal, and that prohibiting the party would threaten American civil liberties; he ended the hour with a rousing account of the damage done by the Alien and Sedition Acts. The New Yorker was in no sense a consistent civil libertarian—at one point he even favorably cited the Smith Act, which made it illegal to advocate the overthrow of the U.S. government—but relatively speaking, it was clear which candidate was friendlier to the Bill of Rights.

There's a lot more that's interesting about the debate, from Stassen's endorsement of the draft to the ways the fear of Soviet subversion was wrapped up with fear of labor unrest. A good deal of the hour was spent arguing about whether or not a particular bill that Stassen supported would in fact outlaw the party. Here's the whole thing:

Taft, for the record, shared Dewey's opposition to banning the Communist Party. And since Stassen brought up peacetime conscription, I should note that Taft was opposed to that too. If you reflexively associate conservatives with the repressive side of the Cold War and liberals with the defense of dissent, the 1948 primaries should add a little nuance to those stereotypes.

Dewey went on to win both the primary and the nomination, then lost to Harry Truman in November. Stassen became a perennial presidential candidate and Mad magazine gag. And the Communists provided the final footnote to the show. According to the website Our Campaigns, "William Z. Foster of the Communist Party asked for equal time to set forth his party's views on the Dewey-Stassen debate. [The Mutual Broadcasting System] set up a debate between Foster and Norman Thomas, the Socialist Party candidate for President. Foster refused to hold a joint debate with Thomas, so MBS backed out."

(For past editions of the Friday A/V Club, go here. For a radio debate between Norman Thomas and a different communist, go here.)

Show Comments (9)