Clarence Thomas Suggests That Permanently Losing Your Gun Rights Is No Small Thing

Maybe Congress needs better reasons to bar people from owning firearms.

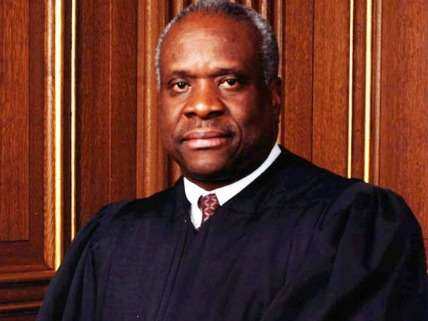

Yesterday, when Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas spoke during oral argument for the first time in a decade, it was to raise an issue that even defenders of the right to armed self-defense often ignore: Under what circumstances can someone lose that right?

The case, Voisine v. United States, poses the question of whether reckless behavior is enough to qualify as a "misdemeanor crime of domestic violence" under 18 USC 922, which prohibits people convicted of such offenses from owning firearms. The two men who are challenging that interpretation of the law, Stephen Voisine and William Armstrong, were convicted under Maine assault provisions that cover an offender who "recklessly causes bodily injury or offensive physical contact." Among other things, they argue that reading the federal law to include mere recklessness makes it more vulnerable to challenge under the Second Amendment.

Yesterday Thomas seized on that point and expanded it during an exchange with Assistant Solicitor General Ilana Eisentein. "You're saying that recklessness is sufficient to trigger a misdemeanor violation of domestic [assault] that results in a lifetime ban on possession of a gun, which, at least as of now, is still a constitutional right," he said. "Can you think of another constitutional right that can be suspended based upon a misdemeanor violation of a state law?" Eisenstein could not.

Thomas noted that Voisine and Armstrong, assuming they're covered by 18 USC 922, would permanently lose their Second Amendment rights, even though their crimes did not involve guns or any other weapons. Then he posed a hypothetical: Imagine that a publisher commits a misdemeanor by violating a ban on using children in certain kinds of advertising. "Could you suspend that publisher's right to ever publish again?" he asked. Eisenstein thought not.

"So how is that different from suspending your Second Amendment right?" Thomas asked. Eisenstein replied that Congress had "the compelling purpose" of preventing escalating domestic violence by people with a demonstrated propensity to commit such crimes. She also noted that misdemeanants can seek to recover their Second Amendment rights by petitioning for a pardon or expungement.

Although the resolution of this case probably will not hinge on the issue raised by Thomas, federal courts will need to contend with it if they take seriously the constitutional rights recognized by District of Columbia v. Heller, the 2008 decision that overturned a local handgun ban on Second Amendment grounds. Depending on who chooses a replacement for Antonin Scalia, who wrote the majority opinion in Heller, that decision could be reversed or applied so narrowly that it has little practical impact—a prospect to which Thomas alluded when he said owning a gun is a constitutional right "at least as of now." But even assuming that Heller continues to impose restrictions on gun control, it is not at all clear what those restrictions will be, especially when it comes to rules about who is allowed to own firearms.

Although Heller itself blessed "longstanding prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill," those categories include lots of people who, unlike Voisine and Armstrong, have demonstrated no violent tendencies at all. If a misdemeanor assault conviction does not justify stripping someone of his Second Amendment rights, why would a felony conviction for selling marijuana or involuntary treatment for suicidal thoughts? Other disqualifying criteria listed in 18 USC 922, such as illegal use of a controlled substance or unauthorized residence in the United States, seem even more tenuously related to the goal of protecting the public from violent criminals. If the right to armed self-defense is guaranteed by the Constitution, Thomas is rightly suggesting, perhaps Congress should not be so quick to take it away.