Cruz, Like Trump, Plans to Stop Heroin With a Wall

The Texas senator says "we will end this deluge of drugs" by securing the border.

In a recent column, Ann Coulter says Donald Trump is the only presidential candidate who understands what it will take to stop "the drug overdose deaths sweeping the nation." The answer, of course, is to stop heroin from entering the country. What didn't anyone think of that before?

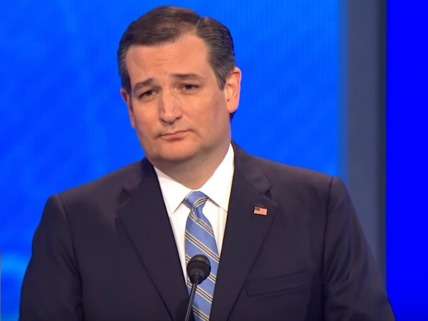

"Absolutely none [of the Republican candidates] but Trump would consider building a wall on our border," Coulter writes, overlooking Ted Cruz, who promises to "build a wall that works, triple border security, and put in place the surveillance and biometric tracking [required] to secure the border." During the Republican presidential debate on Saturday night, the Texas senator said fighting heroin abuse requires "securing the borders, because you have got Mexican cartels that are smuggling vast amounts of heroin into this country." Cruz insisted that "we know how to secure the borders," that "what is missing is the political will to do it." He promised that "as president, I will secure the border," and "we will end this deluge of drugs that is flowing over our southern border and that is killing Americans across this country."

The idea that the government could "end this deluge of drugs" if only it tried in earnest is the mark of an unreconstructed drug warrior who has not learned anything from a century of failure at that task. Bill Bennett, John F. Kelly, Donald Trump, Ann Coulter, and Ted Cruz may believe it, but no one who understands the economics of drug prohibition does. Posit a wall along our southern border, and you can be sure that drug traffickers will find ways over, under, around, and through it. If drugs can get into prisons, they can get into the United States as long as people here want them, no matter how much political will we summon or how much money we spend on border security.

In Coulter's view, pointing out that demand drives supply in the market for heroin (or anything else) amounts to "blam[ing] America first." If it weren't for those nasty Mexicans "dumping these poisons on our country," she says, the number of opioid-related deaths would not have reached a record high of more than 29,000 last year.

One reason to question that claim: Almost two-thirds of those deaths involved not heroin but prescription narcotics. Furthermore, the recent increase in heroin use was driven largely by people who started with painkillers and switched when a government crackdown made the pills harder and more expensive to obtain. That transition contributed to the increase in opioid-related deaths as people accustomed to reliable doses of legally produced narcotics started using a black-market substitute whose purity is inconsistent and whose margin of safety is smaller.

The more fundamental problem with Coulter and Cruz's supply-side approach is that it's impossible to foist drugs on people who do not like them. Heroin has never appealed to more than a tiny percentage of Americans; based on past-month use reported in last year's National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), marijuana is about 50 times as popular. If supply created demand, the heroin market would continue to grow until everyone in the U.S. (including Coulter and Cruz) was taking heroin every day. Instead it remains, as always, a minority taste, even among people who use illegal drugs.

There is nothing inevitably lethal about indulging that taste, and heroin-related deaths are not simply a function of heroin use. Between 2007 and 2014, according to the NSDUH, past-month heroin use increased by 170 percent. During that same period, according to the CDC, heroin-related deaths increased by 340 percent—twice as much. Rather than ask how heroin makes its way to people who like it, anyone interested in reducing the harm it does should ask why heroin users are more likely to die from drug poisoning than they used to be. Part of the answer seems to be the shift from prescription painkillers to a riskier replacement, which in turn highlights the ways in which prohibition makes heroin more dangerous than it would otherwise be—in particular, by making potency unpredictable.

It is also important to note that a large majority of so-called heroin overdoses (about two-thirds in 2013, according to the CDC's data) involve combinations of two or more drugs. Discouraging such dangerous mixing could reduce fatalities even without reducing heroin use. Likewise easier availability of the opioid antagonist naloxone, which reverses heroin's effects, and legal protections for people who report overdoses (a.k.a. Good Samaritan laws). Such harm reduction policies are more likely to make a dent in opioid-related deaths than the border wall Trump and Cruz want to build.

Show Comments (50)