The Bernie Sanders Delusion

Like Ralph Nader and Jerry Brown before him, the Democratic socialist believes that Americans would embrace his progressive agenda if only it wasn't for the campaign finance system.

For those who nurture an ideology that has never achieved significant electoral power in the United States, it can become all too easy to believe that only shadowy cabals and/or single-structure impediments are blocking reforms that would otherwise be broadly popular. If only we got rid of X, goes the belief, Policytopia would be within our grasp.

But enough about libertarians. (I kid, I kid.) Bernie Sanders, the Democratic socialist, is the latest iteration of a recurring political character over the last quarter century—the progressive stalwart from "the Democratic wing of the Democratic Party" who believes that progressive policies are being held back not by a more centrist public, but by a corrupt campaign finance system. Like Jerry Brown in 1992 and Ralph Nader in 2000, Sanders appears to sincerely believe that a political revolution lies on the other side of eliminating superPACs.

"We've heard a lot of great ideas here tonight," Sanders said, with contestable accuracy, at the end of the last Democratic presidential debate. "Let's be honest and let's be truthful. Very little is going to be done to transform our economy and to create the kind of middle class we need unless we end a corrupt campaign finance system which is undermining American democracy." The solution? "We've got to get rid of superPACs, we've got to get rid of Citizens United, and what we've got to do is create a political revolution which revitalizes American democracy." That's all.

Sanders' opening statement at the debate bemoaned "a corrupt campaign finance system where millionaires and billionaires are spending extraordinary amounts of money to buy elections." His first answer promised "a government that works for all of us, and not just big campaign contributors." Asked about the questionable political viability of national single-payer health care, in a country where Obamacare has almost never polled north of 50 percent, he said this:

Do you know why we can't do what every other country, major country, on Earth is doing? It's because we have a campaign finance system that is corrupt, we have superPACs, we have the pharmaceutical industry pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into campaign contributions and lobbying, and the private insurance companies as well.

Detecting a theme?

There were no questions at the debate that couldn't be steered back to campaign finance reform; no left-of-Obama policies that couldn't be depicted as popular among the public. Asked how he might bring a polarized polity together, Sanders responded:

The real issue is that Congress is owned by big money and refuses to do what the American people want them to do. The real issue is that in area after area, raising the minimum wage to $15 bucks an hour, the American people want it. Rebuilding our crumbling infrastructure, creating 13 million jobs, the American people want it. The pay equity for women, the American people want it. Demanding that the wealthy start paying their fair share of taxes. The American people want it. […] The point is, we have to make Congress respond to the needs of the people, not big money.

Do the American people really want these policies? Not exactly. Taxing the rich is certainly always popular as a general proposition. But on "pay equity," a HuffPost/YouGov poll in 2014 found just 32 percent favored legislation to fix the male/female pay gap, compared to 37 percent who considered the current laws to be "about right." Everybody wants to "rebuild our crumbling infrastructure," but when you start asking specific trade-off questions, like the Reason-Rupe poll did in 2014, you'll see that, sure, 46 percent of Americans want more transportation-infrastructure spending, but 73 percent say the federal government spends existing funds inefficiently, 85 percent are opposed to raising the gas tax (which funds most road infrastructure), and 58 percent preferred tolls over more gas taxes. A Sanders policy mandate that does not make.

What about a $15 minimum wage? This idea is overwhelmingly popular in expensive liberal cities like New York, but there isn't a lot of national polling data on mandating #NewYorkValues (or L.A. values, Seattle values, or even Long Beach values!) on the federal level. A Hart Research Group poll from last year found 63 percent support for a $15 federal minimum wage by 2020, but we could stand to see more Gallups and Pews weigh in on the specifics. Even making big-city minimum wages mandatory on the state level has run into opposition from bona fide blue governors like Jerry Brown (about which more below), for reasons that almost certainly have more to do with economics than campaign contributions.

Watching Bernie Sanders repeatedly hack the debate conversation back to how campaign finance was single-handedly blocking the broadly popular progressive agenda gave me a powerful feeling of déjà vu. Sixteen years ago I watched another indefatigable old northeastern progressive make the same case in the same way, day after anti-"corporation" day. Like 2016 Sanders, Ralph Nader in 2000 caught fire with a progressive left disillusioned with the coronation of an unlovable establishmentarian (Al Gore was nobody's leftist back then), drawing some of the biggest crowds of any candidate that year. (It has largely gone down the memory hole, but Nader filled Madison Square Garden and dozens of arenas around the country to paying audiences.)

Nader was fond of saying, then as well as now, that "Most of our stands and positions are supported by most Americans." As I once uncharitably observed,

Most Americans, it seems safe to wager, are not in favor of abolishing the death penalty, doubling the minimum wage, taxing every stock transaction, beefing up the Internal Revenue Service, reorienting the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to "fight global infectious diseases," charging broadcast companies "billions" in spectrum "rent," rewriting the Constitution to create European-style proportional representation, and erecting a Museum of Tort Law in Winsted, Connecticut. Yet Nader seems to believe that if we just remove the corporate blinders from our eyes, Americans will naturally embrace this political program and the Greens will become a "majoritarian" party.

The Naderite/Bernist faith in the popularity of their ideas is part of their unlikely charm (one shared in similar fashion, if not ideology, by Ron Paul). They come off as incorruptible, genuine and principled, all rare and attractive traits in politicians. But charming delusions are still delusional, and Sanders fans who are convincing themselves about the majoritarian appeal of Bernie's policies (even the ones I agree with!) will surely be in for quite a shocker if that rubber meets the road in federal policymaking. Indeed, there's an argument to be made that the Democrats' historic political decimation in statehouses and Congress has come at least partly as a result of the party shifting over the past decade from Bill Clinton-style economics to a more Sanders/Elizabeth Warren-friendly critique.

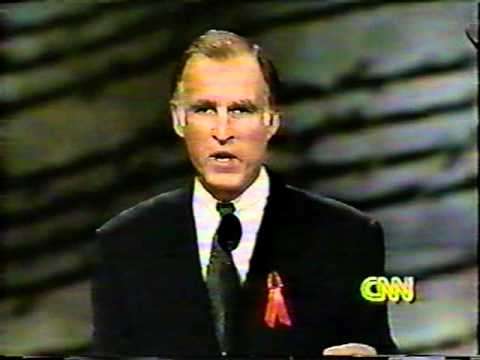

When you see the Nader/Sanders similarities, it's tempting to make sweeping conclusions about a Democratic fringe now becoming mainstream. But this trend is actually nothing new. Want to see the most Bernie-like speech you'll encounter this week? Take a look at the 1992 Democratic National Convention address by Bill Clinton runner-up Jerry Brown, in which the former Governor Moonbeam thunders for the minimum wage, warns of a society "breaking down" over income inequality, calls for the elimination of superPACs, and warns that "there is no such thing as a billion-dollar populist." Some excerpts:

Instead of government by the people and for the people and of the people, President Bush and his allies give us government of, by and for the privileged…. [They are presiding over] the growing concentration of wealth beyond any boundary of nation or conscience and its influence over our governing institutions through money.

Whatever nice programs we speak of, whatever dreams we share, unless the basic fact of unchecked power and privilege is acknowledged and courageously challenged, nothing will ever change. […]

Except for the influence of power and money, how can we explain why high price corporate lunches are tax deductible but not the hard-earned tuition payments of struggling students? You tell me 'cause you know the answer. It's money, it's contacts, it's everything that's wrong with this country. […]

Let's put it simply. The words of politics will remain empty forever unless we challenge and challenge honestly and directly and in a measurable and credible way the corrupt money and the influence that today powers our campaigns and puts our words and faces across TV screens in five and ten and $20 million campaigns. We got to get at that root or we're never going to build the trees of progress.

The disintermediation of political gatekeepers, which Nick Gillespie and I talk about at length in The Declaration of Independents: How libertarian politics can fix what's wrong with America, means that political parties can no longer just wave aside the deeply felt beliefs of their own grassroots. On the Republican side, at least until recently, that meant a resurgence of fiscal conservatism among a new bloc of politicians and their supporters. The Democrats could have chosen any number of issues to challenge their own establishment with; unfortunately (from a libertarian perspective, anyway) they chose Democratic-socialist economics.

Will those policies prove to be majoritarian, as Bernie Sanders and many of his supporters believe? I'll take the under.

Show Comments (362)