This Isn't America's First Freakout Over Refugees

Before anyone was afraid of ISIS terrorists disguised as Syrian refugees, Americans were afraid of Nazi agents disguised as Jewish refugees.

As refugees flee the brutal chaos in Syria, their plight has prompted a lot of talk about the Jews who fled Germany in the Nazi era. Sometimes the people who raise the topic are highlighting the parallels; other times they're trying to draw distinctions. But one similarity between the situations hasn't gotten as much attention as it should. Both crises fed the fears of foreign infiltration that have long lurked within American culture.

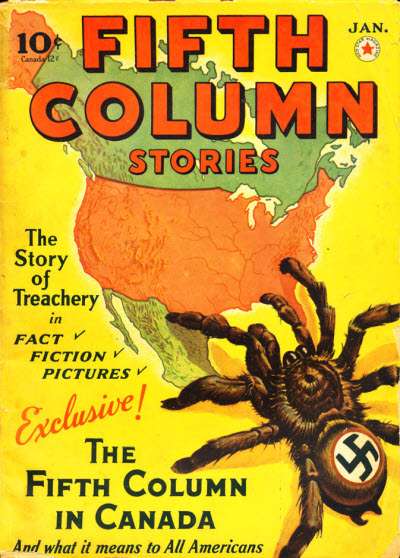

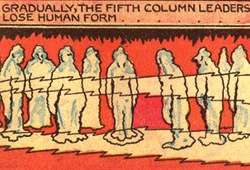

In the late 1930s and early '40s, Americans saw Nazi agents everywhere. In August of 1940—more than a year before Pearl Harbor—Gallup's pollsters knocked on people's doors and asked, "Without mentioning any names, do you think there are fifth columnists in this community?" Forty-eight percent said yes, some of their neighbors were probably secret agents; just 26 percent said no. Those suspicions often extended to the refugee population. The Saturday Evening Post told its readers that Nazis "disguised as refugees" were working around the world as "spies, fifth columnists, propagandists or secret commercial agents." Similar stories appeared in such organs as Reader's Digest and American Magazine, with the latter running a feature that bore the calm, collected headline "Hitler's Slave Spies in America."

The idea in that piece was that the agents among the refugees didn't want to do Hitler's bidding. They simply had no choice, because otherwise their relatives back home would be in danger—an approach the article called a "blitzkreig of blackmail." This theory was endorsed by no less than President Franklin Roosevelt, who said at a press conference that refugees ("especially Jewish refugees") could be pressed into Nazi service with the words "we are frightfully sorry, but your old father and mother will be taken out and shot."

Those worries turned out to be overblown. In Insidious Foes: The Axis Fifth Column and the American Home Front, the historian Francis MacDonnell concludes that "Axis operations in the United States never amounted to much, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation easily countered the 'Trojan Horse' activity that did exist….Though the Germans practiced espionage, sabotage, and subversion in United States, their efforts were modest and almost uniformly unsuccessful." In American Refugee Policy and European Jewry, 1933–1945, Richard Breitman and Alan Kraut point out that "fewer than one-half of one percent of all refugees arriving from Nazi-Soviet territory in 1940" fell under enough suspicion to be brought in for questioning; just a fraction of those were indicted, and "most of those were violation of immigration regulations rather than espionage."

Furthermore, one of the best defenses against infiltration turned out to be the refugees themselves. After the American ambassador to France, William Bullitt, declared that "More than one-half the spies captured doing actual military spy work against the French army were refugees from Germany," the anti-fascist writer Heinz Pol noted not merely that the number was far smaller than that, but that the handful of pseudo-refugees who did exist were frequently caught with the assistance of refugee organizations, who after all were especially eager to work against Hitler. (Significantly, Pol's argument appeared in The Nation, which at that point in its history was very susceptible to fears of foreign subversion. The magazine ran a regular feature, called "Within Our Gates," devoted to exposing alleged fifth-column activities; one installment argued that "every German alien in the country" except the refugees and obvious dissidents "must be presumed to be doing everything within his power to undermine the United States.")

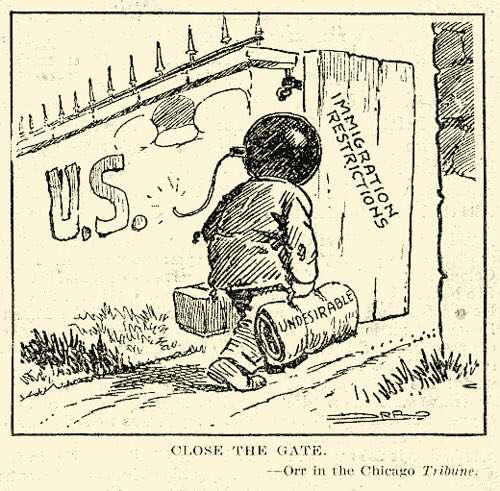

But fear carried the day. "Instead of adding reasonable screening precautions to the existing immigration procedures," the Holocaust historian Rafael Medoff writes in Blowing the Whistle on Genocide, "the State Department exaggerated the threat, and Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long used it as a pretext to cut in half the use of the already small quotas" of Jews permitted into the country. That was in 1940; in 1941 Long tightened the number yet again. By 1944, Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau would write a blistering memo complaining that State Department officials had "not only failed to use the Governmental machinery at their disposal to rescue Jews from Hitler, but have even gone so far as to use this Government machinery to prevent the rescue of these Jews." Medoff argues that the State Department was rife with anti-Semitism at the time, and that this fed its eagerness to choke off the flow.

Today, of course, the fear is that some of the Syrians seeking refuge in America are actually terrorists working for ISIS. More than half of the nation's governors have announced that they don't want the refugees settling in their states, and at least one Republican presidential contender—Texas Sen. Ted Cruz—has suggested that Washington impose a religious test on the would-be immigrants, letting in the Christians and keeping out the Muslims. One governor who is also a Republican presidential contender, New Jersey's Chris Christie, says he would bar even "orphans under five," suggesting that perhaps he was paying too much attention to last week's chatter about Baby Hitler.

The opponents of Syrian immigration will surely argue that ISIS terrorists are not obliged to follow the same strategies as Nazi spies or saboteurs; the fact one fear was overblown, they'll say, does not prove another anxiety is also mistaken. And it is certainly true that some agents of one sort or another have hidden themselves among a flood of exiles. During the Mariel boatlift of 1980, the Cuban government undeniably inserted some spies among the people fleeing to the United States. (Though it's not completely clear who came out ahead in that operation. American investigators identified several spies, put them under surveillance, and in the process uncovered at least one Cuban agent who had set up shop in the U.S. before the boatlift.)

Yet the fact remains that refugees receive the toughest screening of any immigrant group coming to these shores, with extra layers of scrutiny and a process that usually takes more than a year. There are, bluntly, much easier ways to get a terrorist into America. But if you don't want more Arabs in America anyway, you can scare people into backing your agenda by fanning those fears of infiltration. Much like those State Department flunkies who didn't like Jews.

Show Comments (110)