A Nation of Smugglers and Protectionists

Americans have always limited trade-and always defied those limits.

Contraband: Smuggling and the Birth of the American Century, by Andrew Wender Cohen, W.W. Norton, 384 pages, $27.95

As arguments about trade agreements occupy the headlines yet again, the Syracuse University historian Andrew Wender Cohen has come along to put those debates in historical context. As Cohen's engaging book Contraband details, the American story has been filled with disagreements about how free trade should be, with outright efforts to discourage economic engagement with other countries at all, and with gleefully clever schemes to thwart those efforts illegally. Both limits on trade and the defiance of those limits are intimately tied up with America's concept of itself and Americans' understanding of patriotism. Especially through the 19th century, citizens clashed over whether respect for the national identity required strictly controlling passage across the borders or if it meant leaving them open.

The basic arguments have changed little in the past two centuries. One side invokes nationalism, higher wages, the cultivation of domestic industries, and a purported concern over the conditions of foreign labor. The other points to economic efficiency, lower prices, and the freedom to buy, sell, and choose as you please.

One man who helped people exercise that freedom to choose was Charley Lawrence, whose story threads through Contraband. Billed upon his peaceful death at home in 1890 as the "King of the Smugglers," Lawrence was a confidant of Boss Tweed, a cousin to the poet whose verse is inscribed inside the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty, and an importer of much of the fine silk brought into the country in defiance of America's prohibitive tariffs. After Lawrence was arrested and extracted from his refuge in Britain (smuggling was not an extraditable offense, so the U.S. government lied about the charges), the prominent economist David A. Wells publicly compared him to John Hancock, the founding patriot who had made a fortune ignoring British trade restrictions.

Smuggling goods past despised customs collectors was, in fact, a celebrated occupation during the colonial and revolutionary period. That early embrace of the swashbuckling outlaw speeding goods across the border lives on in the culture in the form of fictional heroes like Han Solo. We may forever wrestle over the policies that create them, but we always seem to love our smugglers.

After independence, the new republic became more nationalist and protectionist. Public opinion diverged in different directions, with some Americans, especially in the North, seeing restrictions on international trade as a means of protecting growing industries and high wages from more efficient competitors and cheaper labor overseas. By contrast, consumers without manufacturing investments, especially in the South, saw high tariffs as a scheme for subsidizing inefficient factories at their expense.

After the Civil War, with the North triumphant, protectionism became something of a litmus test for patriotism, as a nationalism verging on xenophobia swamped American political life. "Lawrence's sin," Cohen suggests, "was not trafficking in textiles per se but, rather, challenging the authority of an insecure national government, exposing American industry to global competition, and tempting consumers with foreign luxuries."

As Cohen's language suggests, in this period protectionism took on a moral quality independent of economic arguments, with high tariffs acting in the role of sumptuary laws. In Cohen's words, it "was becoming less about guarding American workers against competition—though this strain of thought never disappeared—and more about preventing the development of what some saw as a hedonistic, aristocratic country." There was also a fear that free trade would open the marketplace to increased participation by women, by depressing men's wages so that wives were "forced" into the workplace, even as it introduced exotic imports that they aspired to purchase. For decades, the traditional family with one male breadwinner earning enough to purchase familiar American products was a standard feature of protectionist propaganda.

That idealized image of recognizable, homey goods purchased from within the national borders was emphasized again and again. Luxuries from libertine Europe were seen as worthy of exclusion at all costs—or at least at the price of expensive duties.

Under the Mongrel Tariff of 1883, foreign paintings and sculptures were taxed at 40 percent. Enforcing this was a particularly challenging task for Customs agents, because highly portable specialty goods couldn't be assessed by your usual political appointees. The government had to rely on a small pool of experts in the field—the same people doing the smuggling. A short list of names rotated through roles as expert witnesses and defendants, year after year.

Similarly creative approaches were needed to detect smuggled glass, metal, sugar, and other goods that could easily disappear into warehouses, stores, and homes once past the Customs House. Government officials were paid bounties for detecting contraband goods. To get a sense of what that meant, imagine if IRS agents got a percentage of each dollar they squeezed from unwilling taxpayers.

The result of all this smuggling wasn't just cheaper goods. The modern right to privacy largely grows out of legal challenges to Customs agents' power to demand access to ledgers and papers on mere suspicion, a practice quickly and understandably derided as a tyrannical exercise. In Boyd v. United States (1886), the U.S. Supreme Court found that Customs demands for private papers violated the Fourth Amendment's protection against unreasonable seizures as well as the Fifth Amendment safeguards against self-incrimination—commonplace constitutional concepts now, but innovations at the time. Boyd continued to be cited in privacy cases for decades to come, including the Griswold v. Connecticut decision expanding access to contraception.

Trade restrictions became less onerous after 1913, when the 16th amendment opened up another source of revenue by allowing the federal government to tax income. Around the same time, the feds started directly regulating businesses and explicitly prohibiting disfavored goods, such as drugs and alcohol. So the Customs House simultaneously lost importance both as a lifeline for the government and as an enforcer of political preferences. Arguments over wages, industry, and personal tastes remained as fierce as ever, but many of those debates moved into different areas of policy.

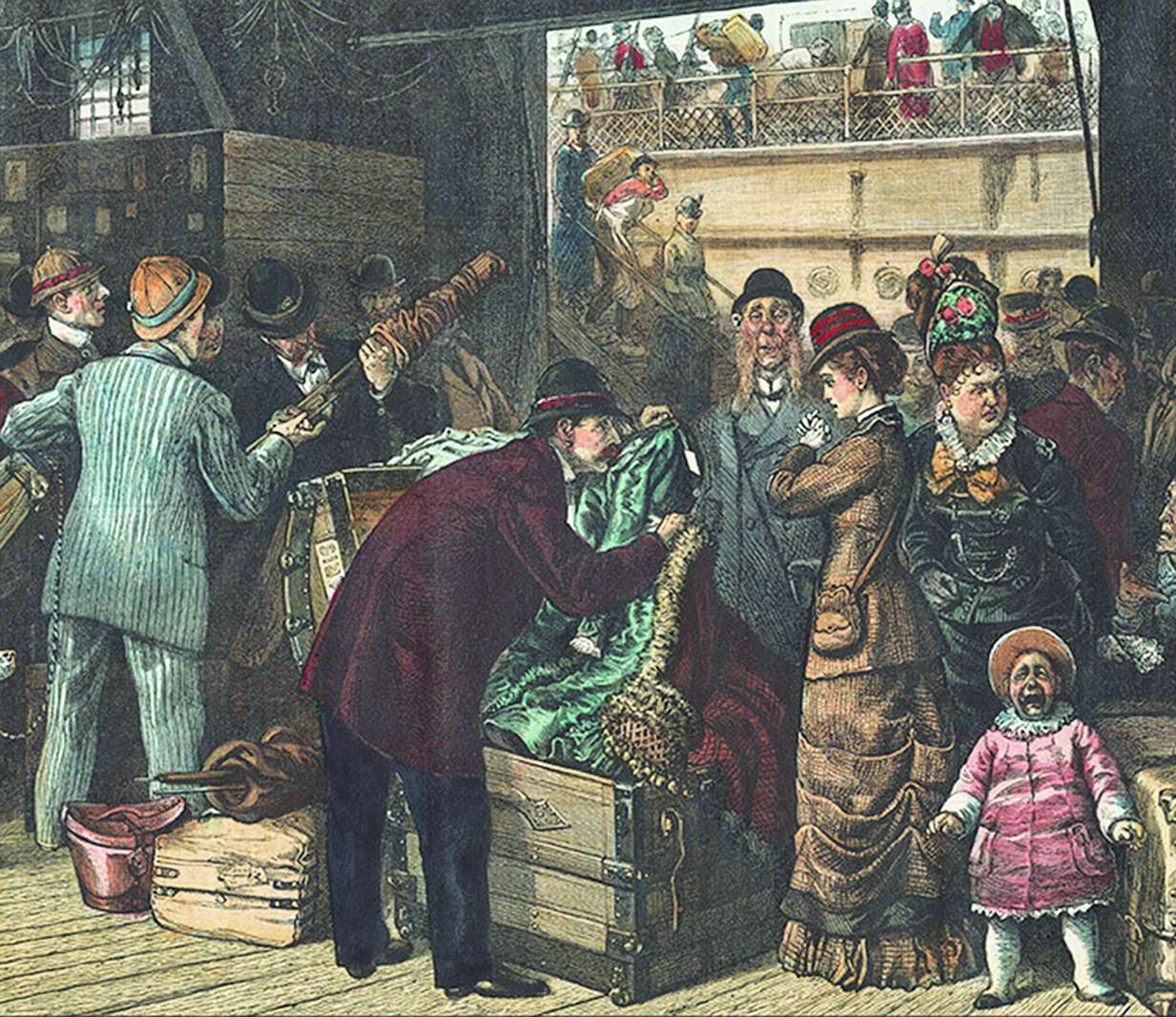

For readers bedeviled by intrusive searches at airport checkpoints, perhaps there's some cold comfort in knowing that Customs officials once subjected tourists returning home on steamships to similar indignities while looking for undeclared silks, jewels, and other small valuables. Even strip searches were common, based only on suspicion and familiar-seeming profiling of travelers.

Or perhaps that's just a nugget of evidence that even if the federal government is someday deprived of its Transportation Security Administration and war on terrorism, it will just find new excuses to grope our crotches.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "A Nation of Smugglers and Protectionists."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Mercantilism was the economic model used by England and the rest of Europe during the colonial period and one of its core assumptions was that wealth was a fixed entity, and it's the reason why England required its American colonies to trade domestically. Adam Smith happened to get published the same years as the Declaration of Independence was signed and the rest was history. Well, sort of, as this article shows that a mercantilism mindset has lingered on.

lingered is perhaps not the most appropriate word. mercantilism and its foundation - the assumption that trade is a zero sum game - remains the favored trade philosophy of scoundrels, the ignorant and statists everywhere. It is one of the most virulent cancers of modern political thought, having atrophied the national conversation about immigration to unanswered nativism. tariffs themselves, when they enter the discussion, are justified today using the exact same protectionist fables that were already disproven 200 years ago.

if there was ever a means to provoke feelings of utter contempt for wretched humanity, it would surely be the study of public opinion toward trade.

I think most, or at least many, people who say they are for 'freedom' are quick to limit the freedoms of others when it's in their self interest. I guess they think freedom means the freedom from competition...

Both of those historic phenomenon were useful to America. 'Protectionism' oscillated between revenue tariffs (better than income tax) and truly protectionist tariffs. With both the result was a lower/middle class that was able to have more job/income security (less vulnerable to Marxist or social welfare siren calls) even if it came at the cost of middle/upper class paying more for some goods. And if those tariffs were bypassed by smugglers - golly thats even more benefit for the lower rungs since they are the ones more likely to break the law (less to lose) and reap a benefit. I prefer a society where the lower rungs have the opportunity for stability and growth - and aren't dependent on welfare/charity.

Ricardian free trade is not absolutist religion. As economics, it requires that the winners compensate the losers. Since the winners never do compensate the losers, it is no more valid than the same utilitarian winners v losers of 'protectionism'. Further, there is a difference between 'free trade with stable currencies' (Ricardo assumption) vs 'free trade with unstable currencies' (alien to Ricardo). In the latter, much of the benefit of trade accrues to neither the buyer nor seller. It accrues to a third party who imposes themselves into the trade (via central bank and govt) to extract economic rent by selling currency hedges.

Prefer free trade but very skeptical about advocates of it.

as Michelle explained I am startled that any body able to earn $8039 in four weeks on the internet . Check This Out ............

http://www.infopay50.cm