Don't Want No Scrubs: Environmentalists and State Regulators Agitate to Ban Plastic Microbeads

Several states side with environmentalists in banning a longtime ingredient in popular products.

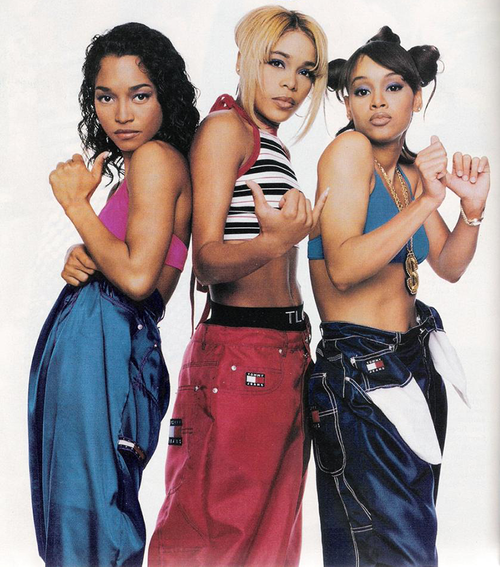

In 1999, TLC passionately remonstrated against scrubs—that is, men who would be "lookin' like trash," while the ladies of TLC and their acolytes were "lookin' like class."

In that day, scrubs trying to up their game could take a trip to CVS and buy some affordable, exfoliating facial wash. Today, however, environmentalists and state regulators are working to proscribe the plastic microbeads that are a key ingredient in commercial skin cleaners.

According to environmentalists, plastic microbeads, which are confusingly also known as scrubs, pose an ecological hazard.

A recent report in Environmental Science & Technology (ES&T) received national attention by estimating that "8 trillion microbeads per day are emitted into aquatic habitats in the United States," enough to cover approximately 300 tennis courts. The report bears the caveat: "scientific opinion non-peer reviewed."

Environmentalists are concerned about the potential impact of this effluent on marine ecosystems, arguing that it's theoretically possible "microbeads can transfer contaminants to animals and cause toxic effects."

As of 2013, The New York Times reported that scientists were still trying to establish that plastic in marine habitats has an effect on wildlife and humans, which then was only partially understood:

Scientists are still working through the links of the chain leading back to humans; about 65 million pounds of fish are caught in the Great Lakes each year. Worldwide, the beads have been found in some marine organisms and not in others, and the transfer of poisons from the beads into the bodies of the creatures that eat them is still being established.

It has been shown to happen in lugworms, which live in the North Atlantic, and Dr. Mason said, "If it happens in lugworms, there's a pretty good chance that it's happening in other species."

Lorena Rios Mendoza, an assistant professor of chemistry at the University of Wisconsin-Superior,…has examined fish guts and found plastic fibers — possibly from the breakdown of synthetic fabrics through clothes washing — that are laden with the chemicals, and said she expected to find beads as well.

In February of this year, the Australian Government's Australian Research Council (ARC) reported, "Despite the proliferation of microplastics, their impact on marine ecosystems is poorly understood." They did find that "corals ate plastic at rates only slightly lower than their normal rate of feeding on marine plankton." According to the ARC, "the next step is to determine the impact plastic has on coral physiology and health, as well as its impact on other marine organisms."

The scientists who wrote the 8 trillion microbead ES&T report argue that although some say there isn't enough scientific evidence to warrant banning microbeads, and "though there are gaps in our understanding of the precise impact of microbeads on aquatic ecosystems, this should not delay action."

The title of that report is "Scientific Evidence Supports a Ban on Microbeads."

Regulators across the U.S. seem to agree that the evidence supports a bead ban. Though the federal Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2014 died in the 113th Congress, it was re-introduced in March 2015 and assigned to the House Energy and Commerce Committee. A federal ban may not even be necessary, though, as six states (Illinois, Maine, New Jersey, Colorado, Indiana, and Maryland) have already issued their own. Furthermore, ES&T reports that Unilever, The Body Shop, IKEA, Target Corporation, L'Oreal, Colgate/Palmolive, Procter & Gamble, and Johnson & Johnson pledged to stop using microbeads in their "rinse-off personal care products."

Critics, including the ES&T authors, charge the bans and voluntary moratoria don't go far enough, as some of the language (like "rinse off" and "personal care") provides loopholes for products defined as having other applications. Furthermore, the ill-defined term "biodegradable" still permits plastic beads that degrade only slightly while still posing, in the critics' view, a potential hazard.

Fortunately, you can clean your face without dirtying your conscience. A vertitable trail mix of safe, organic material, "including rice, apricot seeds, walnut shells, powdered pecan shells, [and] bamboo," can be found in earthy commercial exfoliants, and they are said by some to work even better than plastic. On the other hand, the crunchy skincare alternatives do cost more, so a "broke-ass" scrub may still be out of luck.

Show Comments (90)