What It's Like to Explain Jury Nullification to a Sitting Judge

Don't assume I agree to enforce absurd laws.

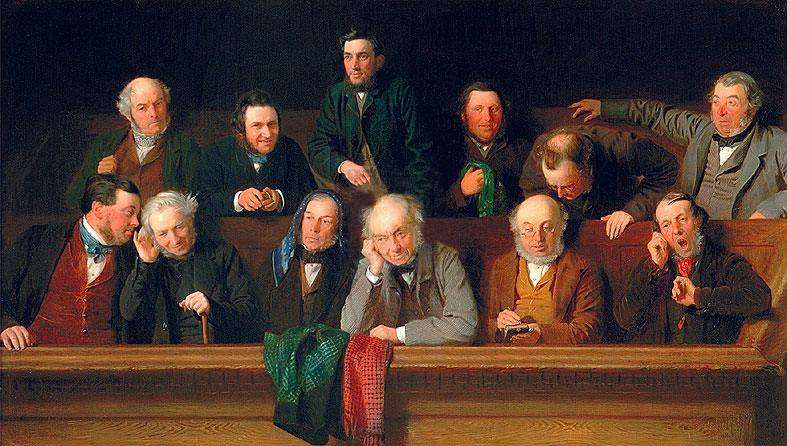

I spent a day last week immersed in Los Angeles County's immense judicial system downtown after being summoned to jury duty.

My experience was not quite as vividly terrible as Matt Welch's in New York, partly because Los Angeles lets you complete your questionnaire and orientation videos online well in advance, and thus I was permitted to arrive late and stroll in after all the dreadful lecturing. And then I just sat around most of the day, having courthouse cafeteria jambalaya for lunch so bad it actually inspired fascination rather than disgust. ("Where did they find sausage that tasted like nothing? How is that even possible?")

I wasn't called for a panel until very late in the afternoon. I actually worried that I was going to end up dragged back on Thursday (debate day!) just to complete jury process. There were about 35 of us, and they were handling us in groups. But fortunately I ended up in the first group, and the judges and lawyers decided who to keep and boot group by group.

Before we were brought into the courtroom, we were all handed a questionnaire intended to determine any biases we might have toward races, or police officers, or criminals, et cetera. Of interest to me was the very first question, which asked us to agree that we would apply the laws as instructed, even if we disagreed with said laws.

I very much have a Lysander Spooner-esque concept of jury duty. The juries are not just there to determine innocence or guilt, but to act as a check on runaway authoritarian criminalization and the increasing network of confusing laws that are passed with neither the approval nor oftentimes even the knowledge of the citizenry.

I have also never actually served on a jury because I am a journalist and editor. The last time I made it to a panel for jury duty it was for a high-profile fraud case for which I knew loads of off-the-record information that may or may not have come up in trial. Needless to say, I wasn't kept on.

My attitude toward jury nullification was on my mind as we were brought in before the judge, particularly since this was just after a Denver jury nullification activist was arrested for handing out pamphlets, which inspired a piece by Glenn Harlan Reynolds at USA Today the day before my jury service. What was I going to be in for when I said I couldn't agree to the very first question?

The judge, fortunately, was unfailingly polite to everybody. There were absolutely no angry lectures from him to anybody while I was there. Our defendant was a woman accused of attempted murder with a deadly weapon. So unless there was some sort of exaggeration of what counts as a deadly weapon I didn't see the likelihood of jury nullification becoming an issue. There weren't even any other charges being piled against the woman for refusing to accept a plea. Just this one. (Later the defense attorney would ask us if any of us had ever been stabbed.)

But the judge, when talking about the questionnaire at the start of the process, said he was going to assume that all of us actually agreed with the first question, and that we would be willing to convict somebody of a law regardless of whether we agreed with such a law. I certainly was not going to agree to that and wasn't about to lie that I would under oath.

He started by letting people who wanted to try their luck at begging to get out of jury duty for extreme hardships or just to reschedule for a better time. Then he started going juror by juror getting some history from them (occupation, previous jury service, friends in law enforcement), then asking if they had any problems with any of the questions. People were allowed to talk to the judge and lawyers in a sidebar if there were problems that were particularly sensitive (like details of having previously been crime victims).

When the judge got to me, I gave him my basics (including identifying myself as a journalist and editor) and that I hadn't been on a jury before. He then repeated his assumption that I agreed with the first question and asked if I had problems with any of the other questions.

"Well, actually about that first question," I began, and then explained that I believed that jurors had the right to nullify laws that they thought were inappropriate. I then clarified that personally for me this mostly applied to cases where there were no actual "victims" connected to a criminal charge (drugs, vice, et cetera) and that I didn't think it would apply in this case.

The judge didn't seem upset about me bringing jury nullification into his court. He nodded his head and repeated what I said to make sure he understood me. I was not lectured for not agreeing to perform my judicial duty as the state sees fit. I was not immediately ejected. I started wondering if I was going to end up on jury duty anyway.

Then the prosecutor asked me what sort of journalism I did, and it was all over. I didn't even have to reveal my libertarian identity (assuming knowing about jury nullification didn't already do that) or my reporting on prosecutorial misconduct or overreach. All I really had to do is to say that I have written about criminal cases and court rulings in the past. I mentioned writing about California State Sen. Leland Yee's arrest and charges of corruption. She asked me if I would be willing to set aside what I had read about the law in other cases for this jury. I said I would, but she obviously must have thought I knew too much. When it came time for the prosecution and defense attorneys to challenge (and eject) jurors, I was the first one bounced out of there. And then I was done.

But she didn't ask me about jury nullification at all, so I was left wondering if I still could have gotten on that jury if I didn't have my experience writing about court cases to doom me. I'll probably never know, because I will probably never, ever get seated on a jury, not that this will stop them from making me drag myself down there every couple of years.

Show Comments (59)