The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Pennsylvania's governor doesn't understand economics (or won't admit the real reasons he vetoed ending state liquor monopoly)

In Pennsylvania, you can only buy wine and liquor from state-run liquor stores, run by the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board. As you might expect, consumers often face higher prices and less selection as a result. Restaurants - particularly those that seek to maintain high-end wine cellars - can face their own set of problems (unless they're willing to skirt the law, as many do). Growing up in Philadelphia, I knew many folks who would buy their wine and liquor elsewhere, such as in Delaware or New Jersey. Many folks living in southeast Pennsylvania would load up on booze (in addition to fresh Jersey tomatoes) when coming back from the Jersey Shore in the summer.

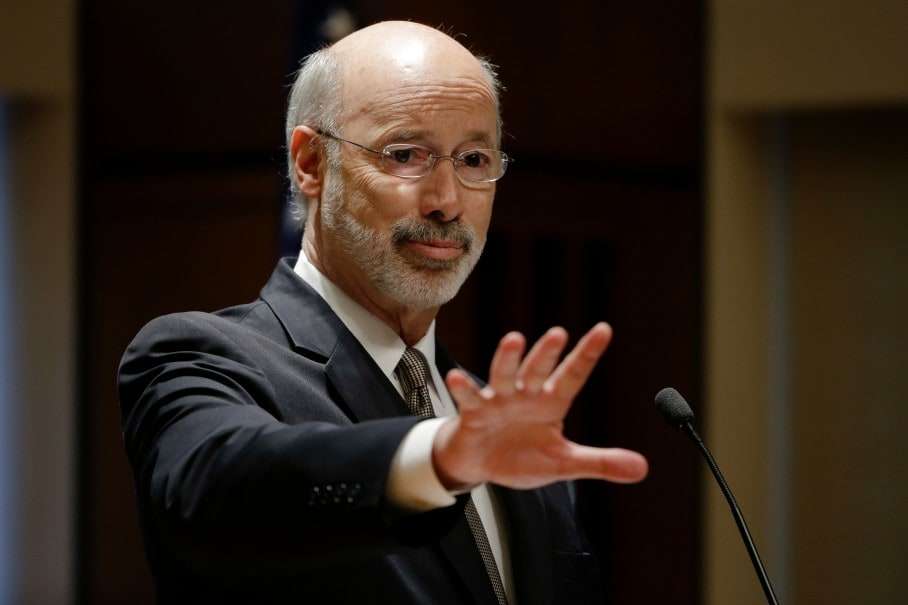

This week both houses of the Pennsylvania legislature passed a bill to end Pennsylvania's state liquor monopoly - but it was not to be. Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf vetoed the legislation, claiming allowing private wine and liquor sales would lead to "higher prices and less selection" for consumers. No, really. That was the explanation. Read it for yourself.

Reason's Jacob Sullum explains why the governor's arguments are ridiculous:

According to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Wolf and his fellow Democrats "warned that prices would rise as private businesses sought profit." In other words, private merchants will jack up prices because they want to make money-unlike the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board (PLCB), which seeks only to raise revenue. If you think those two motives sound pretty similar, you are smarter than Pennsylvania's governor, who fails to recognize that the relevant difference between these two models for distributing booze, when it comes to how high prices can be raised, is the presence or absence of competition. Other things being equal, more competition leads to lower prices, so it is hard to see why Pennsylvanians would have to pay more for a bottle of whiskey if the state monopoly were replaced by profit-driven businesses competing against each other.

If you compare the prices charged by the PLCB to the prices charged by, say, Total Wine & More across the border in New Jersey, you'll find that customers generally pay more for liquor in Pennsylvania: for example, just picking three products I often buy, $30 vs. $25 for Bulleit rye whiskey, $52 vs. $44 for 10-year-old Ardbeg Scotch, and $44 vs. $37 for Herradura reposado tequila (all in 750-milliliter bottles). Total Wine also has a bigger selection: 354 varieties of Scotch, for instance, compared to fewer than 100 at the PLCB. Is there any reason to think Total Wine could not offer similar prices and variety to Pennsylvanians?

The prediction of higher prices is not only inconsistent with basic economic principles and the experiences of the three dozen or so states that already have private liquor sales

It's true that liquor prices went up after Washington State privatized liquor sales, but that's because the privatization initiative was paired with a substantial tax hike. Washington State has the highest liquor taxes in the country.

There are plenty of other reasons why Governor Wolf might have wanted to veto liquor store privatization. One would be the loss of state jobs to the private sector. Another might the opposition from beer wholesalers who worried about an increase in competition. In other words, signing the bill might have crossed powerful constituencies that benefit from the status quo - even if they benefit at the expense of consumers. It's also possible that the governor feared that privatizing liquor sales would make alcohol taxes more transparent, thus limiting a potential source of state revenue, or that he feared (as union opponents of privatization argued) that privatization would increase alcohol abuse and alcohol-related accidents - but that argument was premised on privatization making alcohol less expensive and more readily available. Oops.

If Governor Wolf believes the explanation he offered for vetoing the liquor store privatization law, he does not understand basic economics and is immune to empirical evidence. More likely, then, he had other reasons for the veto - reasons he'd rather not share publicly.

Show Comments (0)