Clarence Thomas and the Confederate Flag

Understanding Justice Thomas' vote in Walker v. Sons of Confederate Veterans.

Yesterday the U.S. Supreme Court issued two very different opinions in First Amendment cases. First, in Walker v. Sons of Confederate Veterans, a 5-4 majority held that the Texas Department of Motor Vehicles did not violate the Constitution when it refused to create a specialty licensing plate bearing the image of the Confederate battle flag. License plates, the Court held, are not venues for private expression protected by the First Amendment, they are forms of government speech. Then, in Reed v. Town of Gilbert, the Court struck down an Arizona town's regulatory scheme governing the placement of signs on public property. "Ideological messages are given more favorable treatment than messages concerning a political candidate, which are themselves given more favorable treatment than messages announcing an assembly of like-minded individuals," such as signs giving directions to Pastor Clyde Reed's weekly church services. "That," the majority held, "is a paradigmatic example of content-based discrimination."

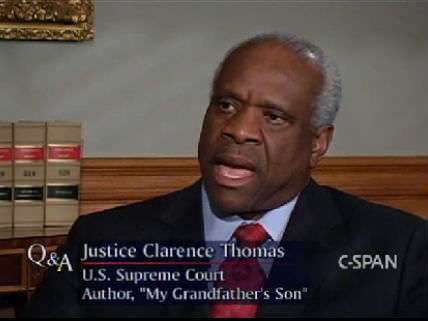

Justice Clarence Thomas voted differently in these two cases. When it came to the Confederate flag license plates, he joined Justice Stephen Breyer's majority opinion, standing alongside liberal Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan, to find that no First Amendment violation had occurred. In Town of Gilbert, on the other hand, Thomas authored the majority opinion invalidating the local ordinance on free speech grounds. Thomas' majority opinion in that case was joined in full by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Antonin Scalia, Anthony Kennedy, Samuel Alito, and Sonia Sotomayor.

Writing at The Atlantic, Garrett Epps theorizes about why Thomas might have joined the liberal bloc in one First Amendment case while writing for a mostly conservative bloc in the other. Epps writes:

Why would Thomas cross over in the Sons of Confederate Veterans case? To state the obvious, Thomas is the Court's only African American. Much has been made of his rejection of contemporary civil-rights orthodoxy. But it is equally clear that Thomas retains vivid and bitter memories of his poverty-stricken childhood in the Jim Crow South—and that he retains a particular hatred for the symbols of Southern white supremacy.

Justice Thomas did not write separately in the license plate case to explain why he joined Breyer's opinion, so we may never know for sure why he voted as he did. But Epps' theory is plausible. Indeed, if you survey Thomas' writings, speeches, and opinions over the years, you will find both a deep knowledge of America's racist history and a firm commitment to learning the lessons of the past.

For example, during oral arguments in the 2003 case of Virginia v. Black, which dealt with the constitutionality of a state law criminalizing cross burning, Thomas drew on his firsthand experiences growing up in the Jim Crow South. There was "almost 100 years of lynching and activity in the South" by the Ku Klux Klan and other racist terrorist groups, he reminded the courtroom. "This was a reign of terror, and the cross was a symbol of that reign of terror." A few months later, Thomas cast a lone dissent in the case, arguing that cross burning should find no protection under the Constitution. "Those who hate cannot terrorize and intimidate to make their point," he declared.

Thomas may very well view the Confederate flag in the same unforgiving light.

Show Comments (29)