Pamela Geller is a Terrible Poster Child for Free Speech—and Against Islamist Extremism

Bigotry kneecaps the case against radical Islamism

Here's what I think about activist Pamela Geller's recent "Draw the Prophet" contest in Garland, Texas, where two wannabe jihadists were killed trying to carry out a terror attack: Geller had every right to organize that contest, and she should not be chided for supposedly abusing that right. When extremists use deadly violence against speech that offends them, tut-tutting "just because you can do it doesn't mean it's a good idea" is unseemly and misguided.

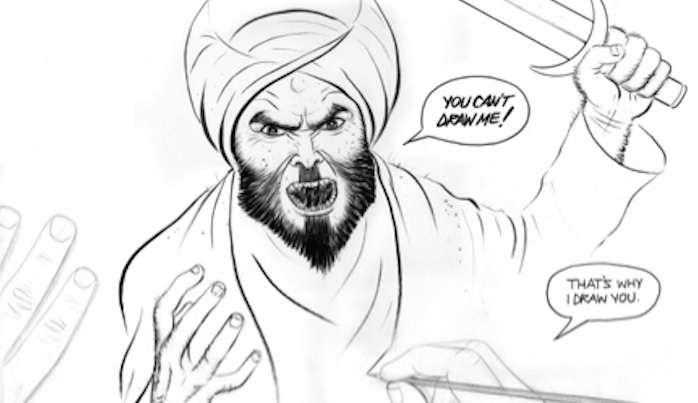

I also believe that, as I argued in The Daily Beast, Geller and her associate Robert Spencer are terrible poster children not only for free speech, but for combating Islamist extremism—because they routinely blur the lines not only between "anti-jihadism" and a war on Islam, but between criticism of Islam and Muslim-bashing. I don't believe Mohammed cartoons are an attack on Muslims, and I actually thought the contest winner made an excellent point. However, as I documented, Geller and Spencer have spent years stoking anti-Muslim hysteria. I'm not fond of the term "Islamophobia," which lumps together criticism of a religion and hatred toward its adherents; but "bigotry," in this case, is not too strong a term.

In their "rebuttal" on Breitbart.com, Geller and Spencer call my article "vicious and dishonest." Without turning this into a point-by-point exchange, some of their charges must be addressed.

I have no interest in polemics over whether, as Geller and Spencer claim, reformation in Islam is a quixotic project ruled out by Islamic doctrine and scripture. People who have deeply studied Islam and political Islamism, and can hardly be accused of naïveté—such as historian Bernard Lewis or Middle East analyst Reuel Marc Gerecht—disagree. Even as strong a critic of Islam as Ayaan Hirsi Ali has come to believe reform is possible. Geller and Spencer cite liberal Muslim Thomas Haidon, who back in 2005 agreed with Spencer that a reformist movement cannot succeed unless it offers "coherent and irrefutable evidence" that its version of Islam is "the 'correct Islam.'" They do not mention that in the next sentence, Haidon lists several Islamic scholars who he believes have done just that. Nor do they acknowledge his warning against "destructive commentary" that undermine reform "by attacking Muslim reformers as 'stupid,' naïve and useless"—the kind of commentary that is their stock in trade.

That aside, the Geller/Spencer piece offers a striking example of why Spencer, the duo's putative scholar, is simply not trustworthy as an expert.

Defending Spencer's claim that the relative tolerance toward Jews in medieval Islam (compared to Christian Europe) is a politically correct myth, Geller and Spencer quote the 12th Century Jewish philosopher Maimonides—who "lived for a time in Muslim Spain and then fled that supposedly tolerant and pluralistic land"—on the mistreatment of Jews by "the nation of Ishmael." The passage they cite, which refers to specific instances of persecution, is the subject of considerable debate among scholars as far as its context and interpretation. But what's not in dispute is that when Maimonides left Spain after a fanatical Muslim sect came to power, he headed to other Muslim countries: Morocco, present-day Israel, and finally Egypt, where he eventually became the Sultan's personal physician. His actual view of Christianity and Islam, and of the Jews' relationship to both, was complex and on the whole probably more favorable to Islam. These are, to say the least, misleading omissions.

Geller and Spencer accuse me of omissions of my own when it comes to Spencer's sympathetic statements about moderate Muslims. Yes, in more than a decade of blogposts on Spencer's site, JihadWatch, one can find such occasional lip service—nearly always in the context of stressing the isolation of moderate Muslims and the hopelessness of their cause. (For the record, the besieged "Moroccan cleric" Geller and Spencer credit Spencer for praising, Ahmed Assid, is actually a secularist intellectual and Berber nationalist.) But did I misrepresent Geller and Spencer's treatment of Muslim reformers, past and present? Two examples will suffice.

- I wrote that Spencer "ignores the work of such 20th Century thinkers as Mahmoud Mohammed Taha, who made the case for the abrogation of the Quran's later, harsher texts by the earlier, more peaceful ones." Spencer and Geller counter by citing a 2014 JihadWatch post in which Spencer notes that the Sudanese government executed Taha for heresy, and a 2006 guest post "on the death of Mohammed Taha." I was prepared to concede error until I checked the links. Spencer's post from last year is a long critique of a statement by Muslim scholars denouncing ISIS as un-Islamic; the reference to Taha is a throwaway line challenging one of their assertions (that Islam forbids declaring people non-Muslim unless they have declared disbelief). This has little bearing on my point: that Spencer's claims about the lack of theological basis for Islamic reform ignore scholars who have formulated such a basis.As for the 2006 guest post, it's about the wrong Taha: Mohammed Taha Mohammed Ahmed, a Sudanese journalist (and moderate Islamist) abducted and killed by terrorists. The sloppiness would be laughable if it weren't for the tragic subject matter.

- Geller and Spencer dispute my assertion that they conducted a smear campaign against American Muslim reformer Zuhdi Jasser in 2011; they think it was a "spirited and substantive disagreement." Well, Jasser thought it was a "vicious attack" and "libelous character assassination." The Geller/Spencer piece also congratulates Spencer for defending Jasser against attacks by the Council on American-Islamic Relations last year. But that "defense" was mainly a broadside against CAIR and a rebuttal to its accusations against Spencer himself; Jasser got about 90 words in a 750-word piece.

Meanwhile, here's what Spencer has said about moderate Muslims:

"I have maintained from the beginning of this site and before that that there is no reliable way to distinguish a 'moderate' Muslim who rejects the jihad ideology and Islamic supremacism from a 'radical' Muslim who holds such ideas, even if he isn't acting upon them at the moment." (From a 2007 post on an Israeli Arab politician caught aiding Hezbollah; a correction notes that the culprit was a Christian, but Spencer clearly felt that his point still stood.)

"The first thing we would have to do is…understand that really, anybody who professes the Islamic faith, if he delves into the teachings of his own religion, is somebody who could end up being very dangerous to us." (From a 2010 debate at Thomas More College, where Spencer argued that "the only good Muslim is a bad Muslim"—one who doesn't follow and probably doesn't even know the tenets of his or her faith.)

And then there's this advice from Spencer's elusive ex-associate Hugh Fitzgerald:

"Understand how very useless is the concept of the 'moderate' Muslim—because it is impossible to know when someone's 'moderation' is real or feigned. Experience shows that Muslim dissimulation—whether called taqiyya, kitman, or simply dissimulation—comes naturally. Also, by his mere presence a 'moderate' Muslim can swell the ranks, and hence the perceived power, of Muslims… And also because even the 'moderate' can be transformed, sometimes very quickly, into the 'immoderate' Muslim, or can have children who themselves will turn out, in a seeking-your-roots or disaffected-from-the-West attitude, to become 'immoderate.'"

(So much for Geller and Spencer's charge that I can't "produce an actual damning quote" to support my claim that Fitzgerald—whom they describe as a "former writer" for JihadWatch, but who was vice president of its board of directors—describes even peaceful Muslims as a threat to the West.)

Geller and Spencer say that I wrongly accused them of opposing Muslims' First Amendment freedom to worship; the article I cited, they claim, merely shows Geller backing legitimate zoning concerns about the building of a mosque. In other words, we are to believe that when Geller posts a screed titled "Mosqueing the Neighborhood," she is concerned only about traffic congestion and noise, just as she would be if it were a megachurch. Unfortunately, there is ample evidence that the wave of opposition to mosques and Muslim centers following Geller's campaign against the "Ground Zero mosque" was steeped in overt religious animus. And there is Spencer's 2010 blogpost candidly stating that "it is entirely reasonable for free people to oppose the construction of new mosques in non-Muslim countries."

As it happens, the same blogpost offers additional evidence for another charge Geller and Spencer decry as unfair: that they routinely distort and mislead to whip up hysteria about "creeping sharia." One of Spencer's examples of the mosque menace is that here in the U.S., mosques have demanded that "non-Muslims conform to Islamic dietary restrictions." The link leads to another JihadWatch post about "stealth jihad in Knoxville," where a mosque was allegedly seeking to "impose Islamic restrictions on alcohol upon non-Muslims."

The mosque, it turns out, was objecting to the planned opening of a restaurant with beer, music and dancing less than 200 feet away. But is there anything uniquely Islamic about such objections? Knoxville has a city ordinance that prohibits selling alcohol within 300 feet of a house of worship (with a loophole for establishments that have a state liquor license). In Texas, that notorious sharia stronghold, such a prohibition is mandated by state law; twenty-four other states and numerous municipalities restrict the sale of alcohol near places of worship. In 2011, a Baptist church in Queens, New York tried to block a beer and wine license for a hookah lounge next door, arguing that alcoholic beverages were unacceptable "in God's sight." Somehow, Geller missed this shocking religious tyranny right in her backyard. But she reported the Knoxville dispute under the not-at-all-hysterical tags "AMERABIA: LOSING AMERICA" and "CREEPING SHARIA: AMERICAN DHIMMITUDE."

Geller and Spencer also devote much space to defending their debunked horror tales of jihad in our midst.

- They state that Sulejman Talovic, the Bosnian-born 18-year-old killed after a shooting spree at a Salt Lake City shopping mall in 2007, wore a necklace with a miniature Koran and "was described as a religious Muslim, attending mosque on Fridays and praying outside of mosque." In fact, the 745-page FBI report on the shooting said that Talovic had stopped attending mosque once he started working in 2004 and that coworkers never saw him praying. It also concluded that he was not motivated by jihad. (Geller and Spencer clearly think the Koran necklace suggests otherwise; but, interestingly, such necklaces are apparently viewed as profane and even idolatrous by devout Muslims.)

- They insist there was evidence of a jihadist connection in the October 2005 suicide-by-homemade bomb of University of Oklahoma engineering student Joel Hinrichs, citing reports (from WorldNetDaily) that "'Islamic jihad' material" was found in Hinrichs's apartment and that he had belonged to a mosque previously attended by September 11 conspirator Zacarias Moussaoui. But Geller and Spencer fail to mention that none of those rumors were substantiated. The FBI, after an exhaustive investigation, found no evidence that Hinrichs had extremist views or had planned to enter the stadium; the terse note he left on his computer indicated no motive beyond suicide.

- They insist that we can't be sure Virginia Tech shooter Seung Hui Cho wasn't a jihadist Muslim, since the "Ismail Ax" inked on his arm remains unexplained. Never mind that the only religious references in the video rant Cho sent to the media were Christian: he compared his imminent death to that of Jesus and spoke of being "impaled upon a cross" by his perceived tormentors.

- Bizarrely, they argue that Geller showed "commitment to accuracy" by deleting a post titled "Vehicular Jihad in Arizona"—based on a news report about a car crashing into a storefront and on the dead driver's Muslim name—when it turned out the "jihadist" had suffered a heart attack while driving. Journalism 101: if you have published a false report, and a defamatory one at that, the decent thing is not to scrub it but to post a retraction and an apology.

Geller and Spencer also try to rescue the "sharia judge" canard circulated in 2012 about Pennsylvania magistrate Mark Martin. As I wrote at the time, Martin had chided a complainant—atheist activist Ernest Perce, who was accusing a Muslim immigrant of harassment—for insulting Muslim sensibilities with a Halloween costume that lampooned Mohammed. For this, Judge Martin was rightly criticized. But the story also generated a firestorm based on reports that he told Perce, "I'm a Muslim, I find it offensive." The judge was quickly confirmed to be Lutheran, and even National Review's Andrew McCarthy, who had initially promoted the story, agreed that his remark had been misheard in the audio of the court session. Geller continued to insist that Martin said he was a Muslim and probably was one; she and Spencer still do.

(In a hilariously karmic postscript, Geller's Muslim-bashing atheist hero, Perce, is now a rabidly anti-Semitic preacher leading a fringe Christian ministry—just the kind of hero Geller deserves.)

On the subject of Geller's tendency to excuse or deny Serb war crimes against Bosnian Muslims, Geller and Spencer respond to the charge of "genocide denial" by claiming that the Bosnian Muslim genocide is a subject of legitimate debate. As proof, they cite a 2005 Yale Human Rights and Development Law Journal article which questions the "genocide" classification of the 1995 Srebrenica massacre of 7,000-8,000 Bosnian males. But the passage they quote clearly shows that the debate is on whether the massacre qualifies as genocide or the somewhat lesser offense of "crime against humanity"—not on whether it happened, or whether the perpetrators were criminals or anti-jihad resisters. "War crime denier" may sound better than "genocide denier," but not by much.

Finally, Geller and Spencer defend a post by Spencer vilifying Kurdish fighter Arin Mirkan as a jihadist because she carried out a suicide bombing against ISIS troops in a besieged town. Their position seems to be that any suicide attack, even in combat, is morally unjustifiable. That's debatable (there were kamikaze-like suicide missions by Allied pilots during World War II). But, morality aside, Spencer's post was ludicrously ignorant: it labels Mirkan, a soldier in the military wing of the left-wing, secular Democratic Union Party, a "Kurdish Muslima."

Geller and Spencer end their screed with an absurd accusation: that I wrote my article because I see them, not Islamist terrorists, as the real enemy. Their social-media acolytes have suggested other motives: that I am afraid of Muslims and am trying to placate them, or that I am a "dhimmi" eager to please my Muslim overlords. (This uncannily echoes hostile responses to my critiques of gender-war feminism: I think false accusations are a bigger problem than rape; I'm trying to placate the patriarchy because I'm afraid of male violence; I'm a man-pleaser.)

In fact, I wrote my article mainly for two reasons:

- I believe radical Islamism in all its forms—the ISIS version or the official Saudi version—is the greatest challenge and danger of the twenty-first century, and the Geller/Spencer way of dealing with it is highly counterproductive. Incidentally, I agree that many critics of "Islamophobia" tend to downplay the very real problems of jihadist terror, of the entrenched power of oppressive, fanatical Islamist ideology in much of the Muslim world, and of radicalization in Muslim communities. But panic-mongering "anti-jihadists" give those critics ample ammunition—for instance, by jumping on fake news stories of sharia on the march.

- I abhor the demonization of any group, especially in the name of a goal I support—be it men demonized under the guise of feminism, or Muslims of anti-Islamism.

Along with missives from Geller/Spencer fans urging me to buy a Muslim prayer rug or predicting my sexual enslavement by ISIS, two emails thanking me for the article are particularly relevant. One was from a man who asked not to use his name, a self-described secular Jew who said that he was a fan of Geller's until he started to find her behavior "very troubling"—though he still credits her for raising his awareness of radical Islam. In his view, "she will have ended up giving the 'counter-jihad' a very bad name, because she's given the institutional left, as Andrew Breitbart called it, a whole bunch of ammo with which to smear the entire 'movement.'"

The other was from Mohammed Al-Darsani, a Muslim U.S. army officer and veteran whom I first met several years ago while speaking at the law school where he was a student. Al-Darsani unequivocally condemned the attack on the Texas event and stressed that the rights of Geller and Spencer (and their supporters) "should be steadfastly protected." But he also added, "It would be nice to see them use their fifteen minutes of fame to issue a statement of unequivocal support for honest, hard-working Americans who happen to be Muslim [and] to thank Muslim United States Military Servicemembers for their service and sacrifices." Al-Darsani readily acknowledges that "there are significant problems concerning hatred and violence in many predominately Muslim communities and sects"; but he wishes Geller and Spencer would acknowledge that "that is not the whole story."

These messages go to the heart of why I wrote my article. I stand by every word.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Geller is the perfect poster child for free speech. She is also the perfect poster child for assholes. Make 2 posters if you want, but for fuck sake get a clue on what Free Speech means.

Ms Young thinks that you have to play the game. You have to say things like, "Islam is the religion of peace." or Obama's line: "The future does not belong to those who insult the prophet."

Only then will Ms Young leave out the "but" in the phrase "Yes, we have free speech, but..."

Sorry, but I hate radical Islam, but I don't like "moderate Islam" like that practiced in Saudi Arabia. Do I like liberal Islam? Peace loving, liberal Islam is a myth in the minds of liberal leftists.

Ms Geller speaks the truth. Her bus ad campaigns were the truth. The leftists (except for Bill Maher) are afraid to speak the truth.

You apparently didn't read Cathy Young's article.

Yes, it's the white man's (or now woman's) burden to reform Islam - and mocking the absurdities of the dominant extreme version are not helpful to that end.

VG -- Oh yeah, that's the ticket. "It's the white man's burden to reform Islam." Good luck with that.

The only chance we have of reforming Islam is with a few dozen well placed nuclear weapons.

It is the simplest solution. Much like the progtard, the most efficient way of dealing with Islam is to reduce its ranks. Maybe 50-100 million of them contained to one region would be more manageable.

Saudi Arabia practices completely mainstream Islam. To describe it as "radical" is as contradictory as saying that all the kids in Lake Woebegon are above average.

Leftists routinely accuse conservatives of "extremist views" despite those views being held by the majority of Americans.

Wahhabism is mainstream because the Saudi's have spent billions making it mainstream. It stared out as a radical cult.

That's how every successful religion has done it. Gotta spend money to make money, and it seems like the Saudis have done very well for themselves.

Still just a bunch of creepy guys in robes. It's all sex related, the fuglies always need elaborate distractions and rules over people to ever hope of scoring.

And the Sauds fund most of the radical madrassas in other places.

There is not "radical Islam". It is all Islam.

Read the Koran and Hadiths. You know, like Robert Spencer has.

Peace loving, liberal Islam is a myth in the minds of liberal leftists.

Nope. I've lived in Indonesia, and I can tell you first hand that muslims can be just as peace loving as anyone else when they're not living in a country where there's a war on.

-jcr

18% of Indonesians are in favor for the death penalty for disavowing Islam. 72% of muslims there say sharia should be the law of the land. 48% favor stoning as the penalty for adultery.

Again, statisticians will tell you that questions like these tend to underestimate the true percentages.

citation or stfu

The reference for the statistics is here:

http://www.pewforum.org/2013/0.....iety-exec/

That surveys would underestimate actual "politically incorrect" opinions is called the Bradley effect. You can read about it at wikipedia.

You can find many examples of Indonesian muslim moderate behavior by googling "indonesia burn churches". For example, you will find this one article by Pam Geller:

http://pamelageller.com/2010/0.....ches.html/

What a jerk she is. How dare she bring attention to these church burnings.

What's with all these facts you're injecting into the argument? They make muslims look bad.

Bigotry! Bigotry!

78% of internet commenters add bullshit statistics to their screeds to add a false air of credibility.

facts? do you have the mind of a child?

100% of b.s. leftists will dismiss opponent's arguments as "rants" or "screeds" despite there being no rant-like or screed-like qualities to their posts.

Just another way the left says, "Shut up."

Funny video by Andrew Klavan on this phenomenon: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lWHgUE9AD4s

Indonesia is only moderate to the extent that many people aren't that religious. The country has its own cigarette and beer companies, the cities are full of bars.

It's religious citizens are bat crazy - bombing churches and nightclubs, trying to close aforementioned beer company, doing virginity tests on female policewomen etc.

I see this argument all the time: Islam can be moderate - look at Malaysia!

But Malaysia is only half normal because the non-Muslims make it so. And I'm not sure that will last in Malaysia and Indonesia. The nutjobs are getting stronger.

Indonesia is only moderate to the extent that many people aren't that religious. The country has its own cigarette and beer companies, the cities are full of bars.

It's religious citizens are bat crazy - bombing churches and nightclubs, trying to close aforementioned beer company, doing virginity tests on female policewomen etc.

I see this argument all the time: Islam can be moderate - look at Malaysia!

But Malaysia is only half normal because the non-Muslims make it so. And I'm not sure that will last in Malaysia and Indonesia. The nutjobs are getting stronger.

Yes. Ask the people of East Timor how peace loving are the Indonesians. Apparently not that much.

If you want to convince anyone, you do have to play the game (though you don't have to say the things you mention and she doesn't). Unless you want to have an all out war against Islam, just saying "they're all horrible" doesn't do any good.

I am also dismayed at how many people are unwilling to really honestly criticize Islam. But I think that Young does a good job being both critical and not unnecessarily unpleasant toward all Muslims. Most Muslims just want to live their lives and do their thing like everyone else.

Still not understanding the need for criticism of Islam as a religion. Religion doesn't change because of criticism, it changes because of wealth, diverse friendships, and other worldly distractions that remove the need for the illusion.

Peace loving, liberal Islam is a myth in the minds of liberal leftists.

You need to learn a little more about Islam. Sufi Islam is broadminded, peaceful, and gets along well with Christianity in places -- like Mali -- where both religions co-exist. Sufis pose a danger to no one.

Most sufi scholars have supported jihad in the past. One of the attackers in Garland TX was named Soofi which points to some sufi influences in his upbringing. Nevertheless, he still wanted to kill cartoonists.

This. I came in to say that Illinois Nazis were the perfect poster child for free assembly.

X2. As was Larry Flint for free speech. If you're looking for "nice" people to be your poster child you're never going to find one. That's kind of the whole fucking point.

What Larry Flynt did to Jerry Falwell was infinitelty more insulting than draw the Prophet contest. And the left wing media cheered him on. The comparisons between Geller and Flynt are pretty specious.

But Jerry Falwell was a white cishet male fundie shitlord, so it's okay.

It's all OK.

The poster child for free speech (or any right) is always an ugly bastard. You don't need to protect speech nobody objects to, it's precisely because the speech is objectionable that the right to say it needs defending.

Hammer meeting the nail head which needs repeating:

"You don't need to protect speech nobody objects to, it's precisely because the speech is objectionable that the right to say it needs defending."

The left is busily eroding free speech under the guise of "hate speech", "micro-aggressions", and "trigger warnings" whose common denominator is that it is speech that they disagree with.

While I admire the accurate use of an old http://www.snopes.com/language/acronyms/fuck.asp), and still redolent Anglo-Saxon word, I post mainly to agree with your point that Geller's effort is speech and graphic expression, well within our current tradition of protected expression, and the columnist is wrong to make a case that she isn't appropriate. Whoever agrees that she isn't appropriate can start a Pam Geller cartoon contest-we don't need to support a current effort to marginalize en route to silencing effort currently directed at Geller. Certainly not from a libertarian perspective-maybe from a college campus no-free speech zone, though. Yeah, that might explain it-the author might be a recent graduate of the PC-only-expression-generation being churned out by our colleges now.

"Appropriate" for what? Nothing is just appropriate, full stop. You need a context. Geller is certainly inappropriate for certain contexts.

Geller should do whatever she wants. And everyone else should feel free to say what they think of her (just not to say that she shouldn't have said her piece).

Anyone who is physically threatened or attacked solely because they have opinions are poster children for free speech. Is Ms. Young suggesting that the only people that are suitable to be poster children are those with whom she agrees? That turns the concept of freedom of speech on its head.

Exactly. If you wait for nice, clean cut, reasonable people to be censored, you have waited too long and are going to have an uphill battle, if you can win at all. Defense of free speech necessarily involves defending jerks like Larry Flint and jackasses like Jerry Falwell.

As to the charge of "Islamophobia", I think the author ?. and a lot of other reasonable people ?. has made a crucial mistake. It is time to stop taking charges of "Islamopobia", "Homophobia", "Racism", etc seriously. They are almost always attempts to shut down speech, and should be scorned. It is not "Islamophobia" to observe that Islamic countries are backward, violent, intolerant, dirty, and ripe for a resurgence of Victorian Colonialism. It is not "Homophobic" to observe that a great many Gay political activists do not want tolerance, they demand submission. It is not "Racist" to observe that if Al Sharpton was a White Republican using the same tactics, he would probably be in jail.

is SHARIAH EVIL? Open Source Conduct Say yep http://sultanknish.blogspot.co.....jihad.html

Sure it's evil. So is a huge part of the laws of the US state and federal governments. Find me a legal system that isn't evil.

Of course, there are better and worse ones. And Sharia is a pretty bad one in today's context. But it's only different in degree.

If the only people who's free speech rights we had to defend were ones that didn't offend progtard multicultural sensibilities we'd defend no ones speech rights. Your piece tiptoes right up to the edge of the progtard line of "hate speech". But here's hoping that since you rightfully put the cartoon in you piece progtards would have been triggered and run away before reading it.

Personally I'm done with pretending all culture are equal. Some are just inferior and shoulde be forced to change if they want to play in the modern world.

The fucking terrorists in this case being conferred victim satus by the left nauseates me.

So we are supposed to find someone who loves Islam but hates "radical Islam"?

Shocker: I don't like moderate Islam, say that practiced in moderate Saudi Arabia. Women can't drive. They behead as many people as Iran. Converting to Christianity is punishable by death. The flog victims of rape.

Is that "bigotry"? So I am not an ideal poster child to speak freely against radical Islam? Does Cathy Young think I have to ignore these things so that the liberals will defend my free speech?

Who the hell thinks Saudi Arabia practices moderate Islam? Not Cathy Young --

Did you even read her article before ranting?

"Counterproductive," i.e. deemed nekulturny by our betters.

There is that. But I also don't see how it is terribly productive. Attacking someone's religion isn't often a good way to convince them to change their mind.

Please enlighten us on the "-Stan" or other Islam-inspired country that we may consider moderate? Pakistan? Yemen? Syria? Egypt? Kazakhstan? Iran? Libya? Somalia? Please do tell.

There is a common denominator in much of the unrest, torture, murder, terrorism, oppression, rape, hate, etc. in this world. Political correctness is not going to solve this one.

The author is using Geller for her own self-important bloviation. She's just trying to dial in her anti-free-speech sentiments.

Peaceful Islam is dominant in Progderpistan.

+1 internets

Albania, Bosnia, Turkey, Indonesia to some extent. Maybe Kurdistan if you consider it a country.

They are all at least a whole shitload more moderate than Saudi Arabia, who some people here are claiming is moderate.

I don't see why Young should be read as anit-free speech. If someone is going around saying "fuck you" to everyone they see on the street and I tell them that they should stop being so unpleasant, I'm not being anti-free speech. If they want to carry on like that, I'm not going to try to force them to stop. Does Young say that she wants anyone to force Geller to stop what she does?

Albania, Bosnia, Turkey, Indonesia to some extent

Malaysia. Bangladesh, probably?

But it's clear that all the above listed countries are on the periphery of the Muslim world.

Turkey and Indonesia? Hardly.

Turkey and Indonesia? Hardly.

Wait, why are we looking to theocracies to serve as examples of moderation? I wouldn't consider any religiously defined nation to be moderate, regardless of which religion it's under.

When you define the Islam practiced in Saudi Arabia -- the heart of Islam, the site of Mecca -- as radical Islam, you effectively identify mainstream Islam as radical Islam. Saudi Arabia is not some exotic exception to Islam -- it is the *standard*.

It would be like identifying the Vatican City as the seat of radical Christianity. What, then, would be moderate Christianity?

Episcopalian?

Yeah, "radical" isn't the word for the Vatican. But there are certainly more moderate version of the religion.

Thank you for answering this. If you define Saudi Arabia as radical Islam, then pretty much all of Islam is radical and thus we are at liberty to insult it all.

Even in "moderate" Indonesia, 30% of muslims support for death for apostasy. (And most likely the percentage is much higher in that people tend to answer such questions dishonestly.)

Aren't we at liberty to insult it all, radical or not, anyway?

Yep. That's how the concept of free speech works.

All or nothing, no more half measures.

I certainly wouldn't call the Vatican the home of moderate Christianity. They certainly aren't typical of most of the world's Christians.

I could agree that "radical" isn't the right word for the mainstream religion of Saudi. But it certainly is conservative and rigid Islam and not at all moderate.

I find Pamela Geller to be a very attractive woman, and really that is all that matters.

I can't decide if she is D+ or E+. But it is good.

I find Pamela Geller to be a very attractive woman, and really that is all that matters.

Have you considered Lasik?

Would.

Would have. Not now.

It might not be all that matters, but it is important.

Oh, go fuck yourself, Young. No one cares about your pissing match with Geller and Spencer. And of Spencer, I might add, he has a degree in religious studies in combination with being a native speaker of Arabic; you, on the other hand, are merely a journalist who is the embodiment of the Gell-Mann Amnesia Effect made manifest into flesh.

Thank you, HM.

HM, quit holding back! Tell us what you think.

My understanding is that Spencer is descended from Armenian Christians who were expelled by the Ottomans. I don't see how he could be a native speaker of Arabic. That said, he probably knows more about Islam than just about anyone else who has appeared on national TV.

Brigitte Gabriel, another Islam critic, is a native speaker of Arabic.

Young really falls short with this article. Just another voice in the "I believe in free speech, but..." chorus.

My bad- Greeks, not Armenians

Because in his community, Arabic is the common language and Syriac is liturgical language. His church, the Melkite Greek Catholic Church is centered in Syria. Basically, the Greeks who didn't go with the Orthodox church during the schism. Like many children with immigrant parents or grandparents, he was raised bilingual.

OK. I learned something new today. Thank you, HM!

I wonder what Robert Spencer would have to say to Chris "did I mention I speak Arabic fluently" Hedges...

http://www.truthdig.com/staff/chris_hedges#bio

All that education, and yet still. so. stupid.

You mess with HM, you get the horns!

I would hope Spencer would say something like, "Kuss ummak, ibn sharmuta! but he seems too pious for that.

Seconded!

All those in favor that Cathy Young go fuck herself?

Thirded...

And of Spencer, I might add, he has a degree in religious studies in combination with being a native speaker of Arabic; you, on the other hand, are merely a journalist who is the embodiment of the Gell-Mann Amnesia Effect made manifest into flesh.

That's completely unfair.

She's an expert on Islam, having taken World Religions 101 as a freshman at Rutgers.

Well, if that's how it works, I'm going to apply for a cushy think tank job based on my expertise in Russian history and culture thanks to my freshman year survey course!

23-sidkoo, suckaz!

I've seen Lawrence of Arabia. Twice.

I stayed at a Holiday Inn once.

I watched a Shriner's parade.

The problem isn't that Spencer ignores M.M. Taha, the real problem is that ISIS, Boko Haram and suchlike bands of raging savages also ignore him. Don't waste your time quoting stuff like that to me; go to work convincing al-Qaida.

No, no...don't you understand? The writings of a rather obscure Islamic thinker (who was executed for apostasy, natch!) is representative of the theological understanding of all four major madhahib of Sunni Islam. Millions of Muslims look to Taha as opposed to the orthodox Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i, and Hanbali jurists. Therefore, Spencer's arguments are invalid.

At least in the alternate universe in which Young resides. It sounds like a nice place. What quantum flux coordinates shall I input into the Spacetime Regulator?

The fact that poor Mr. Taha was executed for his beliefs (or lack of them) puts the tin hat on the irony of using him as an example of moderation.

I think any read of history can discern key differences between Christianity, which had a reformation, and Islam which would lead them to believe that the latter is likely not to have its own Reformation.

At its base, Islam and Christianity have different origins. The New Testament was written by rebels and outcasts. It structurally accepts that there will be a ruling government that may not be accepting to Christians. "Render unto Caesar that which is Caesar's" is a perfect example of this. Lessons like this exist all throughout the New Testament and give ammo to those wishing to reform the religion such that the State and Religion are not intertwined. Where the NT gives moral guidance, it is almost always explaining how one should treat another person with ultimate judgement reserved for the afterlife. While plenty of people tried (and still try) to enact these teachings at the state level, the pretext is there that this is about individuals interacting with another.

Islam on the other hand was written when Islam was the state. It lays down laws, and explains how people must be forced to live their lives. The entire text of the Koran assumes that a leader is in control and will have the power to punish dissenters.

(Continued...)

I think any read of history can discern key differences between Christianity, which had a reformation, and Islam which would lead them to believe that the latter is likely not to have its own Reformation.

The reality that few in the west acknowledge is that modern militant Islam is the result of Islamic reformation.

Yes! You mention things like Qutb, the Deobandi movement, etc. etc. and you get blank stares.

*Stares blankly at HM*

If you ever want a laugh, read Qutb's description of his time as a foreign exchange student in (someplace in the Midwest, I forget where) during the 1950s.

It was Greeley Colorado and he attended a church dance. I know the exact quote you're talking about:

Again - this is a dance in the basement of a church in 1950 Greeley, Colorado. I think he might be overstating the lasciviousness of this particular encounter.

Then again, knowing Qutb it's possible the entire story is invented. He is the one who claimed the CIA tried to entice him with a prostitute on his boat ride to America in order to steal his essence and cause him to forsake the prophet. #shitthatdidn'thappen

In the old south there is still a fundamentalist remnant that condemns dancing and mixed-sex swimming as lascivious, so this mindset is not unfamiliar. The Church of Christ regularly condemned the Baptists as immoral for their daincin', to say nothing of their willingness to fund orphans and widows.

Social signalling is really the theory of all religio-political life.

It is said that the Chuch of Christ (in the South at least) forbids having sex standing up because it may lead to dancing.

Southern Baptists are just as bad about forbidding dancing, just sayin'.

Have you ever stopped and pondered the tragedy that someone who was completely, bat-shit insane, like Sayeed Qutb, was able to ruin so many lives?

Qutb was SO gay... seriously, look at pictures of him... not that there's anything wrong with that

He thought this Midwest town was a hive of scum and villainy, reeking of sinful infidel wickedness. And that was just at a church dance (I don't I'm kidding about that).

Sayyid Qutb is a tragic figure given his obviously disturbed sexual desires led him to obsess over purity that probably impacted his crazed religious beliefs. I mean, look at this shit:

I'd like to meet some of these round breasted, full-buttocked girls!

But you already knew that, I figure.

There is two minutes I will never get back. Got another?

This is because in the west they have lost religion and cannot fathom that someone may make life-altering decisions based on religious considerations. So if an Australian pediatrician wants to go work at an isis hospital, westeners think that there must be some political, poverty, lack of opportunities, etc except the obvious reason that the guy was religious and the religion says that the caliphate is something worth helping.

Technically, I suppose that is true. I should have used the capitalized Reformation, as I was referring not just to the restructuring of Islam's polity (which certainly happened), but specifically to how the Christian Reformation acknowledged that man was answerable to God, not to a Pope or other State leader/Warlord.

don't tell Ignatius Loyola that

Christian Reformation acknowledged that man was answerable to God, not to a Pope or other State leader/Warlord because the founder of that religion said so:"Give to Caesar what is Caesar's and to God what is God's" or something to that effect.

This could never happen in islam as the founder basically say submit to Allah and to the prophet/caliph (with emphasis on the prophet/caliph who was a warlord anyways).

Marcus Borg, who is otherwise one of those deeply decent progressive Christians who thinks we'd be socialists if we were just really good people, always recasts Jesus's message as explicitly anti-imperial: Augustus was the "son of God," so Jesus's followers claiming the same title for him was a rejection of the Roman Empire, Jesus entering Jerusalem on Palm Sunday as a clear rebuke to the Roman procession into the city, etc.

I'm not as pessimistic about Islam's future as many, as even apparently stiff monotheistic religions that have been around a while can be co-opted to serve whatever ends you want, particularly when people become rich enough that they no longer bother reading their own holy scriptures, but it's worth wondering whether Christianity began with a slightly larger kernel of protoliberalism than most religions.

That's the problem though, it's been the opposite in the Gulf. You have the grandsons of nomadic camel herders now some of the richest men on the planet having the time and resources to get some old time religion as opposed to busting their (camel's) hump to scratch up a living in the sandy wasteland they live in. This money had funded the spread of Wahhabism throughout the Islamic world for the past 60 years. Look at how much Malaysia has changed over that time. Malaysia used to be a pretty chill place where women didn't cover their heads, now after 5 to 6 decades of Saudi-funded mosques and religious schools, the regional joke is that Malaysia is "Saudi Arabia's Eastern Annex".

You also have Indonesia, which is a country with a reputation for being the 'moderate Islamic' country, but which stuck a man in jail for 3 years for drawing pictures of Mohammad.

There was also the time an Indonesian man was sentenced to 5 years in jail for distributing anti-Islamic pamphlets and then 1000 Indonesian Muslims rioted and burned down a bunch of churches because they thought the sentence was too lenient.

Or that third time when Indonesian Muslims protested during the Danish cartoon situation and chanted that the artists should be put to death.

You know - because of how moderate that country is.

Compare those states to the American South, where fundamentalism remains common, but its cultural importance has diminished as entertainment & cultural alternatives have emerged. Especially true in the past decade, as the Internet can make even a backwater much more cosmopolitan by breaking ideological monopolies.

Fundamentalism won't disappear overnight or even in 50 years, but the idea that the rough edges (like, say, moving from murdering infidels to denouncing them on AM radio) can't be smoothed off with several decades of banal American sitcoms and Japanese cat videos seems pessimistic.

I was raised in a family where both of my Grandfathers were country Baptist preachers and both founded rual Churches that are laive and thriving today.

The only people that I have ever heard say the earth is only 8,000 years old are progs trying to convince everyone else that most Christians fully beleive that .

A prog or jihadist athesist that is....

All my people are YECs, hardshell baptists and CoC, mainly. But it's not like they care or investigate it--it's just another doctrine to spout to separate the Good People from the Bad.

They spend most of their time watching satellite tv or listening to music on Youtube, which is where I envision the scions of islamism in 2100. At heart, most people really just want to eat cheeseburgers and sit around shooting the shit, not the dangerous business of cutting out infidels' hearts or saving souls in perilous lands.

The bulk of my friends are also YECs, though with a 6,000 year timeline - I haven't heard of an 8,000 year one. Naturally they also don't believe in evolution.

This is Plano, TX, a wealthy northern suburb of Dallas, btw, to give it some context.

We've had some heated debates about it before (most of them believe in some kind of "water dome" that used to contain the earth that apparently gave ancient men super long lives), but they're normal in almost every other respect, and we generally don't talk about it much because said beliefs don't impact our day-to-day lives in any way.

I'd also like to point out that I find it very odd that growing up in rural KY, with my family largely split between Southern Baptist and Church of Christ, none of them (to my knowledge) are young earth creationists. We did have a snake-handler church in that area, but I didn't know any of them personally.

Then once I leave the boonies and move to a wealthy, cosmopolitan suburb of a wealthy city, I suddenly meet quite a few YECs. It was the exact opposite of what one would expect, given the general stereotypes about rural v. urban areas.

One last thing; I was googling around trying to remember what he said about that water dome I mentioned, and here's a link explaining it.

http://creationwiki.org/Canopy_theory

Ok, compare then, show me where they burnt a church or mobbed up for a death chant.

Pamela Geller is a Jew and Robert Spencer is a Papist. Never forget that. It is a religious war with those two. A religious war that almost got a bunch of people killed.

They both belong in prison.

http://www.thoughtsandrantings.com

You know what else Jews were responsible for?

Ending polytheism?

Bar Rafaeli?

Manischewitz wine? Love the stuff. Tastes like Kool-Aid with ten times more sugar.

Passover Coke?

Kosher l'Pesach Coke? That snake oil?!?!? There oughtabealaw!

Tulpa is sooooo mad.

The Producers?

Providing the intellectual core of late 20th-century libertarianism?

Raphael Mechoulam?

No, that's no true. My dad always get his Christmas lights tangled up and he's a redneck as it gets. 😉

Someone named Patrick is denouncing "Papist[s]"?

The Atomic Bomb?

They belong in prison . . . Nice one. You're a funny, funny little man.

I appreciate your disgust with free speech. And your bigotry. And your antisemitism.

Now go fuck yourself, Nazi.

I can only assume from your criticism of this fine, upstanding gentleman that you're some sort of running dog of the Papist orthodoxy.

And who the fuck call someone a "Papist" these days? Did our new troll fall through a time warp from 1850? (And how many more questions in a row can I ask before the Judge sues me for impersonation?)

You sound like some sort of Mohammedan.

Thou art an affront to the good name of Christendom!

Not religious. No idea what a Papist is. Not even going to look it up.

There's one on this very thread.

Well, I don't care if you like it or not. Or that Pam Geller on almost every issue is a Prog, something I detest. It's extremely unlikely you'd be so upset if some prick gay haters tried to shoot up a gay pride parade.

I'm perfectly fine with the contest. That extremely tiny one trillionth of one hundredth of a percent of Muslims who are extremely murderous don't need coddling and sensitivity. They need to learn we don't belong to them and say as we please.

As for Geller's less than honesty in attempting to change the political landscape, well, you just don't find much honesty in politics from anyone on any side.

Now I'm going to take a big dump then wipe my butt with my Mohammad's face toilet paper. Why? Because I'm a hate filled bigot just asking for it? No. Not at all. I'm going to do it just because I can.

Pics?

I'd love to send you some. But I don't have to crap and don't really have any Mohammed toilet paper, I was just trying to make point.

??? Pamela Geller's an objectivist. She has a blog called 'Atlas Shrugs.' Where'd you get the idea she's a prog?

I read it in numerous Internet comments. Ehhhhhh... what the Hell was I thinking...

Let me rephrase that. I don't know anything about Pam Geller past that she helped put on a free speech event which I fully one hundred percent support.

"Or that Pam Geller on almost every issue is a Prog, something I detest."

Wait, what? She's a Randian Objectivist right?

She is a Prohibitionist.

I think Geller's event was perfect exactly because it highlighted the difference between supposed fundamentalists of Islam and those of other religions. It needed to be done because it provided a stark reminder that there is a sickness in that religion that hasn't gotten better in the past several decades.

BTW: That comment was addressed to Cathy.

Cathy Young is confused. Pamela Geller doesn't want to be a 'poster child' of anything . . . She ran a contest. End of story.

This is the same woman who sans this event is most famous for her efforts to get literal posters up in NYC? You cannot caricature some people!

Us secularists have been fighting Christian Sharia for decades. Now the most vile religion in the world is growing and we have a duty to mock it relentlessly since violence is not an acceptable tactic.

Got to side with Pam Geller on this one.

It is "we" secularists, not "us". You ignoramus.

Sometimes Plug pushes it in so far it puts a lot of pressure on the area of the brain that enables formulation of good grammar.

Awwwh. Got it. He's disabled. 🙂

Exactly.

He should have displayed his "handicapped" sticker before he posted. I would have lowered my expectations and treated him as 'special'.

The correct first-person-plural subjective pronoun among PB's demographic is "us-unz."

They're everywhere shriek. Just waiting to get you and brainwash you into worshipping with them.

Trust no one...

What the fuck is wrong with the editors of Reason? Have they forgotten when libertarian means?

As Robert Tracinski wrote in "The Federalist", there is no 'but' after" I believe in Free Speech". Any 'but' negates the previous statement. Cathy Young's 'but' is "I believe in free speech but Pamela Geller is a terrible poster child". Good God.

I wasn't really expecting to wake up from a night of drinking to find an anti-free speech article on Reason. If I didn't have a headache I certainly do now.

Unfortunately, this isn't their first foray into the land of 'but' . "We believe in libertarianism, but . . .". Apparently, the talented libertarian writers have moved to The Federalist.

We're talking about folks who decided to basically kick Harsyani to curb and replace him with Richman, of all people.

*shrugs shoulders*

Harsanyi still writes here.

Yes, he hasn't been fully exiled, but I remember when Harsanyi was Reason's policy in the Middle-East man. Also that other fella, the Brit...I can't remember his name at the moment. Sadly, those two seem to have been replaced by Richman and his ilk.

HM: yes I'm flatly wrong, but going to keep spinning nonetheless...

Coming from Bo...

It would truly be magical to experience just a moment of the total and complete disconnect from reality that you enjoy on a constant basis. The first pharmaceutical company that can bottle it will be able to purchase their own universe.

Maybe he thinks he can get a guest writing spot if he keeps it up? And given the way weekend trolling articles are piling up, he may well be right.

It's not an anti-free speech article, and the people claiming otherwise are being idiots. It's a pro-free speech article, but Young is just choosing to bury her head in the sand regarding Islam, so people who are more anti-Islam than she is can never be 'good poster children' of free speech.

People really don't appear to understand how widespread horribly violent ideas are among Muslims globally.

BTW, if you actually bother going through the entire Pew poll I mention in that post, you'll find that there among the countries they bothered polling, support for honor killings runs at well over 30%. They polled like 30 Muslim countries, and just in those countries you easily 450-500 million Muslims who support stoning women who cheat on their husbands to death.

Support for this sort of thing is therefore over 1/3rd of all Muslims on the planet. The idea that this is some sort of 'radical fringe' is absurd. If 1/3rd of Americans thought honor killings were justified, no one would be telling me 'well, most Americans are more moderate!' and no one would be saying it's wrong to criticize America when only 100 million of its 300 million citizens support sexist murder.

"no one would be telling me 'well, most Americans are more moderate!' "

I would, because defining any group by what a minority, even albeit a troublingly large minority, of that group believe or do is rank collectivism.

Coming from someone who believes the majority of Reason commenters to be crypto-Republican social conservatives on the basis of a small minority of posters who generally acknowledge themselves not to be libertarians right from the get go...

I wonder if when you finally get so far up your own asshole that you inevitably crawl out of your own mouth a new universe will be born.

About half is closer to the truth, and you'll notice I'm careful to refer to them in such ways PM. You're just mad I spoiled your little playground by pointing it out.

and you'll notice I'm careful to refer to them in such ways

In the sense that a stopped clock is accurate twice per day, I guess. McCarthy had a better hit percentage than you do. Maybe you, too, should try alcoholism. It couldn't do anything but improve you.

Says the guy who lumped ME in with the Offended White Guy Brigade.

That isn't ironic at all.

Check yer womyn privilege, Hamster!

So I shouldn't criticize Communists just because a minority of those Communists starved people to death and murdered tens of millions of people.

Also, Bo, if 30% of Muslims believe in stoning women to death, what percentage of Muslims do you think are in favor of, I don't know, beating your wife, or beating your kids, or treating your wife as a second class citizen, etc? Stoning is such a radically extreme position, that it stands to reason an outright majority of global Muslims hold horrifically sexist views that just stop short of stoning people to death.

Also, I don't have a problem with individual Muslims. I have a problem with Islam, which is easily the worst religion on planet Earth, and is a religion which guarantees a certain percentage of adherents will murder people. Criticizing an ideology is not 'collectivism' you moron because if it was then every time you criticize social conservatives you're engaging in collectivism.

You admit 2/3 disagree but think the whole group should be tarred for the view?

This is basically slight of hand. People are not condemning all Muslims. They are condemning their anti-liberty Stone Age religion that produces massive numbers of sociopathic murdering assholes.

Let's analogize. I bet higher percentages of members of the black community support things we'd both find awful, maybe even as high as 1/3 on some issues. Would saying that the black community is the worst community therefore be ok?

Criticizing an ideology is not 'collectivism' you moron because if it was then every time you criticize social conservatives you're engaging in collectivism.

Well to be accurate, Bo actually does engage in collectivism by placing people of vastly disparate ideologies into the same group, then imagining that they share his caricature of an unrelated ideology, and criticizing them on that basis. It would be analogous to you conflating ethnic Arabs with religious Muslims and criticizing Arab culture on that basis.

What are you talking about? Do even you know at this point?

I don't think that was at all unclear to anybody but you.

It's common to defend someone's right to speak while denouncing the speech and speaker. Someone can burn the flag or paint the Madonna with dung and I can criticize them while opposing coercive measures against them.

Sounds like a very long-winded 'but' to me, Cupcake.

then you cant read

Speech criticizing free speech is protected free speech, too. Let's not forget that.

The only "but" I use is "...but be prepared to face criticism for whatever you say."

Cowardice is common. Men without chests but with manboobs like Bo. C.S. Lewis had no idea how much worse it could get.

Best little rant on a Hillary presidential run I've heard yet.

(Sorry you may have to watch a few seconds of a commercial to hear it.)

Th author seems to think one can be a muslim and reject Islam. Geller and Spencer point out the serious problems that Islam presents to freedom, democracy and western civilization. Are we to understand that adherents of Islam don't present the same problems ? Can Islam be reformed ?Many have tried and all such sects are deemed heretical and ruthlessly suppressed by classical Islam. The authors argument when Godwinized is that Nazism is bad but nazi party members present no problems at all and it would be wrong to criticize them for adherence to their creed.

Are Jews and Christians who have found ways to reconcile the awful parts of their Scriptures with modern sensibilities not really Jews or Christians? How different than comparable Muslims?

For one thing, modern Islam has reembraced the most vile and disgusting parts of the Koran and Hadith.

Where were Judaism and Christianity 1300 years after their foundings?

Christianity was recovering from a half a millenium of victimization by Muslim inspired aggressive war.

Yeah, they were just this oppressed sea of tolerance and pacifism surrounded by aggression.

Where do you think Christianity and Judaism were 1300 years after their founding?

Christianity was burning apostates and treating religious minorities awfully.

Are you seriously going back to this retarded idea of yours that Christianity and Judaism just have a 'head start' and that's why they're less violent?

Hinduism is the oldest religion on the planet, so by your argument Hinduism ought to be some sort of brilliantly advanced philosophy that leads its adherents to enlightenment. Moreover, Islam's early years don't scan with Christianity's early years. At the beginning, Islam was a hyper-expansionist military power that conquered all of the Middle East, north Africa, Spain, India and invaded France. Christianity started off its existence as an oppressed minority religion in the Roman Empire and only gained wide swaths of land when Emperor Constantine converted.

Given that their early years were so substantially different, it clearly is not the case that Islam is just a certain period of time behind Christianity.

All three Abrahamic monotheist religions were intensly and violently intolerant through most of their history until over a dozen centuries after their founding. The difference is Islam was founded much later.

It's like looking at three men all of who were jerks as young men, but stopping the tape for one at that age and then focusing on the fact that the other two grew out of that phase to become fine upstanding middle aged men.

In other words, we should just be more patient while they grow up.

No, we deal with it like we do bad acting young men-taking an unequivocal stand condemning and standing against the bad things they do while hoping they grow out of it.

The young religion hypothesis is bunk. Sikhism is 500 years old and they are not especially violent. Scientology is 50 years old and they are not violent either.

Jainism is older than Christianity and it never had a violent period.

It's not the age; it's the doctrine.

Fair enough point, but it's helpful to limit the comparison to the three Abrahamic monotheist religions I think. When you do it's inescapable that for all three the long stretch of their early centuries were rife with violent inolerance, and that Islam started much later. The intolerance of modern day conservative Islam looks eerily like that which Christianity exhibited 700 years ago.

All right, and where was Christianity 200 years after founding? Now, where was Islam? Can you make a single comparison there?

Christianity was under the boot of the mightiest empire in history, so I'm not sure how many points they get for not causing trouble then. Islamic nations that were under outside domination often behaved relatively well.

Way to go, Bo. You just talked your way in circles.

Either the two religions are comparable or not. As many have said, the two (or three) religions have totally different origins, and so their age/maturity are not comparable. Your answer seems to be "Sure they are comparable...except for these times when their maturity/age present evidence contrary to Bo's sweeping and overly generalized theory."

The fact is that Islam was born from hyper aggressive expansionism. Christianity was a grass-roots insurrection of decentralized communities.

Two thousand years later, Christianity is more or less embraced its founding roots. 1300 years later, Islam has more or less embraced its roots. This isn't shocking to anyone looking at it honestly.

Shorter Bo

It's best to just ignore the reality and believe this false idea that supports my theory.

Quote some of those awful parts from the New Testament why don't you.

Christians don't reject the Old Testament (you might have heard of this fondness they have for something called 'the Ten Commandments' for example). But of course, I'd still be able to raise the example of Judaism. It's adherents are quite peace loving today, but at one time were full of apocalyptic fundamentalists, much like contemporary Islam which, interestingly, is centuries behind Judaism.

So that's a pass thanks for playing. Oh Bo so confident and yet so incompetent. I bet you were mummy's special widdle boy weren't you. It's hard to explain the confidence otherwise.

But they do believe that the New Testament supersedes it. There is a reason why almost every Christian mass reads one or two short passages from the OT and then devotes a half hour to reading and discussing the message in the New Testament.

No, no, no...Young got a letter from a nice young man saying we can forget all that. AND WHY AREN'T YOU THANKING HIM FOR HIS SERVICE YOU BIGOT?!?!?

Of course, "reform" is possible, in the sense that you can turn Islam into a different religion bearing the same name. That's how Christianity and Judaism have "reformed" after all: you declare most of the holy book to be "allegorical", ignore the atrocities committed by its followers and sanctified in its holy books, state that all the killings done in its name were not actually according to the religion. Then you pay off the church hierarchy and have them swear allegiance to the state.

What do you end up with? Another shitty new-age paternalistic movement around, usually tied closely to the government and government finances. While it's a big advantage that its adherents are considerably less homicidal than they used to be, you just created a huge number of statists who have simply traded belief in one kind of oppression for belief in another kind of oppression.

I think on the whole, you're better off weaning people off the Abrahamic religions rather than trying to salvage the unsalvageable.

"I think on the whole, you're better off weaning people off the Abrahamic religions rather than trying to salvage the unsalvageable."

As an atheist, I feel this way about all religions. Religions have done their best work when they stick to charity and "group therapy" in the context of a larger society. Sort of a halfway house for believers, on their way to wholeness and rational thought. Any other 'feature' of religion is about control, in my opinion.

The root of misery is not Religion. It is Statism. Give any state power and it will justify its horrors through whatever contemporary excuse is at hand. For all the terror of the Inquisition this period was a minor blip compared to the Khmer Rouge, the Ukrainian Holodomor or the Chinese Cultural Revolution- all perpetrated by Atheists. These psychos were all "weened off the Abrahamic religions" and they did far worse than any of those villains ever did.

True. But some religions are intrinsically statist; that is how they kill.

You're making a category error there: Catholicism is a specific organization and a specific religion, and a statist one that ran Europe for more than a millennium. In contrast, atheism is not an organization, political philosophy, religion, or ideology, it's just a descriptive term. You might as well say that the majority of atrocities in the world were committed by people who believed in heliocentrism: true, but utterly irrelevant.

Those psychos were not weaned off the Abrahamic religions, they never believed in them in the first place. Furthermore, they did not use "atheism" as a justification for their deeds; their atheism was incidental.

That is in contrast to the numerous atrocities committed by Christians, Jews, and Muslims, directly motivated and justified in the name of God and His teachings. And the Inquisition was really just a blip compared to the huge numbers of people slaughtered by followers of the Abrahamic God in His name.

Scott Walker just on CBS, said we need to have a 'strong presence' in Iraq and called for a Reaganesque 'build up' of our military. Going to be increasingly fun watching his cheerleaders among the right leaning regulars here contort themselves trying to square their support with their ostensible libertarianism.

Just curious what your parents do/did for a living. Were either of them teachers, by any chance?

What did yours do?

Accountant and housewife.

My dad was a missionary primarily, my mom a homemaker. Dad eventually became an administrator for missions.

Implicit in your question is that someone who isn't impressed with Walker must have some irrational reason to dislike him, like a parent that's a teacher. Do you think that much of him?

I'm in a state that's being destroyed by unions. I don't care if the guy has dead bodies in his trunk.

Fair enough. I live in a state misruled by SoCons and where public unions have largely been illegal, so I'm less impressed by him. YMMV.

Gosh, you two should just switch places - win-win!

If you're in a state being destroyed by unions, you are, after all, used to that sort of thing.

"Dad eventually became an administrator for missions."

I don't want to insult your dad, but this explains a lot about you.

An administrator of missions in a relatively small conservative church might not fit what you think of as the usual admistrator for what it's worth.

Dad believed in the message of Christ as a potential personal good for people, much like Ted Cruz seems to understand, and perhaps more importantly he sees the good missions do in materially helping poor people around the world via non governmental efforts.

Like I said, it wasn't meant as an insult of your dad because I have no idea what kind of a person he is. But I can see how his job alone would color your perception of social conservatives, whether you realize it or not, and that is reinforced by your response. You know all about what he thinks about his role, but not what he does.

Bear in mind that anything Bo tells you about his/her back story is very likely completely full of shit.

That is another possibility.

Bear in mind that anything Bo tells you about his/her back story is very likely completely full of shit.

Bo's family portrait

My parents, like most SoCons, are good people that I happen to disagree with on some issues. I've said that over and over here. People here project that I 'hate' SoCons because they hate the 'progs' they disagree with and can't fathom disagreeing with someone that you still respect.

Are we psychoanalyzing each other now?

Barf

Have a seat on my couch, Scruffy. You're in a safe place.

People here project that I 'hate' SoCons because they hate the 'progs' they disagree with and can't fathom disagreeing with someone that you still respect.

Or they get that impression from your idiot-savant-like focus on more-often-than-not imagined SoCon hobgoblins to the near-exclusion of any other political issue, combined with your ardent defenses of progressive political ideals so long as they remained gilded in a veneer of voluntarism, and your enthusiastic agreement on a wide variety of subjects with the commentariat's only two persistent griefers.

Speaking of hobgoblins, it's nice that you describe people concluding what I think from their readings of implications of who they perceive me agreeing with and what I don't say as opposed to, you know, what I actually say.

I oppose leftist policy all the time, but people like you that are so interestingly intent on covering and carrying water for SoCons only recall my criticisms of them.

Speaking of hobgoblins, it's nice that you describe people concluding what I think from their readings of implications of who they perceive me agreeing with and what I don't say as opposed to, you know, what I actually say.

Well, that's not actually what I said, but then if you could comprehend anything you read, you wouldn't be Bo. There was most of a paragraph preceding the:

...and your enthusiastic agreement on a wide variety of subjects with the commentariat's only two persistent griefers.

part.

I oppose leftist policy all the time, but people like you that are so interestingly intent on covering and carrying water for SoCons only recall my criticisms of them.

You also defend progressive political ideals all the time. And it's probably more telling that you accuse me of carrying water for socons when you yourself have admitted when pressed for evidence that I actually am not a socon, than my noticing, along with every other person you happen to have encountered in your time here, your unflappable obsession with socon boogeymen.

As far as Republican politics go, that is the main issue right now: social/Christian conservatism as a political agenda is both incompatible with libertarianism and political suicide for the Republican party as the number of Christian voters is inexorably decreasing.

Note that this has nothing to do with whether your beliefs are socially conservative; I'm pretty socially conservative myself in my beliefs and my own life. Political social conservatism is about imposing one's beliefs on others, and that simply cannot be reconciled with either libertarianism or Republicanism. And many religious conservatives want selective libertarianism, where they continue to demand special privileges, while denying those privileges to others under the pretext of small government. Liberals and progressives take excellent advantage of that kind of hypocrisy.

Your best comment so far! Obsessive stalking leads to impulsive errors there, PM!

Not sure what is so erroneous about that post. Seems to me that PM knocked it out of the park.

I'm sure it seems that way to you, but my comment was to his aborted comment above the one you like so much.

It's cutely narcissistic of you to think that a stranger on the internet failing to press the shift key firmly enough to transform a period into a greater than sign to close an HTML tag properly somehow reflects upon yourself.

defining any group by what a minority, even albeit a troublingly large minority, of that group believe or do is rank collectivism.

Fucking priceless.

Cutting words remove no heads.

Good morning, AC.

Good afternoon, JG.

Reason's writers are getting really good at kicking hornets nests with their weekend articles. Enjoy the shitshow, everyone.

It's not just the writers.

HOW MUCH U NEGLECT UR KIDS BRO

I woke the baby up with an air horn this morning. I'm trying to makeup for lost time.

MLG PARENTING!

MLG PARENTING!

Video?

I have no idea what the author thinks is an adequate "poster child for free speech". She appears to be eliminating anyone with whom she disagrees or is "controversial". Respectfully, that is nonsense. The point of free speech is that it applies first to the controversial. The poster children in the past have been the demonized, blacklisted and ostracized. Geller is perfect just as Malcolm X with whom I agreed about nothing, was perfect.

And just like Communists were perfect poster children for free speech despite my disagreements with them.

Not even on gun rights?

"I'll HUFF, and I'll PUFF...."

Such necklaces are viewed as profane by some Muslims and I think Young's argument here would have been a bit more convincing if her linked source weren't a random Muslim internet forum where some people say you shouldn't do it. An internet forum, incidentally, which contains a poster who says this:

So even in Young's cited source one of the posters mentions that it's actually controversial as to whether this is allowed or not. 'Devout Muslims' can look at this issue both ways, there's no real Islamic orthodoxy regarding the subject.

Think what Frodo coulda done with one of these.

Good spoof! For a minute there I almost believed it was a Reason editor penciling that screed. But no Reason editor would have failed to notice:

1. Pamela's website is Atlas Shrugged, and denounces all manner of superstitious drivel, and

2. That Texans have guns and shoot murdering jihadists. (See American Sniper)

Mohammed's myrmidons would have fared much better in the legally disarmed People's States. But seriously, is Cathy Young an editor at Mother Jones? Utne Reader? People's World?

"When extremists use deadly violence against speech that offends them, tut-tutting "just because you can do it doesn't mean it's a good idea" is unseemly and misguided." And them the author goes on to two pages of doing just that.

Gellar and Spencer's occasionally shrill critique of Islam is, itself, certainly open to critique but doing so in the context of an article that discusses free speech at least pushes toward the "her skirt was too short" territory, disclaimers aside.

If the skirt was shorted kapton insulation could help. What? This isn't a technical forum. Uh.............

"Bigotry kneecaps the case against radical Islamism"

A case of ammo is the only one to be made against savages

And y'all better act right when attending a Texas art show...civility is strictly enforced

Shoot Friendly, The Texas Way.

Neither was Larry Flynt a poster boy for free speech. The ones who get attacked are usually the most obnoxious jackasses. Rarely does the speech of the inoffensive get suppressed.

In many's view, only speech that would never be criticized (the sky is blue, puppies are cute, etc) is worthy of protection. They're just too damn stupid/intellectually lazy to realize that kind of speech doesn't need protection.

Rarely does the speech of the inoffensive get suppressed.

Inoffensive to whom? In most of the world, if you express an idea that only the people in power find offensive, you're thrown in jail or worse.

That's the kind of speech the first amendment is designed to protect -- speech that upsets the powerful. Not speech designed to upset a widely hated and scapegoated minority. The latter is still protected by the first amendment, but this is a necessary evil, not something to celebrate.

There are over 1.57 billion Muslims in the world. If we subtract the number of Muslims from the country's population, my napkin math tells me the ratio of Muslims world wide to the number of Americans citizens is roughly 5 Muslims for every American.

Get out of here with that bullshit.

"Not speech designed to upset a widely hated and scapegoated minority."

Is that minority hated for good reason? Do they pull guns when others unpack pens?

The fact that some group is a minority says nothing about whether what they stand for is worthy of praise, derision or apathy. The same goes for majority groups. Everyone gets judged on their merits or lack thereof, not on where they stand on the victim totem pole.

"Not speech designed to upset a widely hated and scapegoated minority."

.

Just as the Second Amendment was designed to keep the King of England out of our faces and, now that King George III is dead, there's no more need for that particular right either.

.