I Avoided Fighting in Vietnam and Have No Regrets

If anything, avoiding that war was a moral duty.

Hard to believe that 40 years ago the U.S. war in Vietnam ended. Actually, the war was against Indochina: remember Cambodia and Laos. (With previously unexploded ordnance from American cluster bombs killing people in those countries to this day, did the U.S. war really end?)

It's hard to believe because I can remember when I and the people around me thought the war would never end. It seemed like a permanent part of life. Night after night we'd turn on the network news and watch the reports of body counts—always more of "theirs" than of "ours"—yet we had no sense it would ever really end, despite talk of "victory."

When the Gulf of Tonkin "incident" occurred in August 1964 I was getting ready to start high school. I was only beginning to become politically aware. Being from a moderately conservative Republican family and hearing little or no dissent to that point, I assumed "our" involvement in Vietnam was necessary and proper. (I cringe now at what Barry Goldwater, whose pro-freedom rhetoric moved me, was saying about war, Vietnam, and the Soviet Union.)

Proper or not, however, I knew I didn't want "our" involvement to become my involvement. Members of my extended family who were military age looked without shame for ways to avoid what was obscenely called "service," that is, the draft. Flunking one's physical or finding refuge in the National Guard was an occasion for copious sighs of relief. Patriotism was a virtue, sure, but let's not take it too far—that was the attitude. The members of the older generation around me thought the war was a good thing—the communists had to be stopped—as long as no one they knew had to go over there, especially their kids. Dying in a jungle? If it had to be done, that was for other people's kids.

I didn't have Vietnam on my mind constantly while in high school, though I was surely aware that if you didn't get into college, you'd be gone and quite possibly a goner. I just can't recall obsessing about it, or even discussing it with my friends. I guess any effect the war might have on me seemed too far in the future to think about in the present. Maybe we told ourselves that somehow it would be over before we came of age—even as we thought it would remain a fixture of life forever. It was weird; that's all I can say.

Late in high school I bumped into libertarians for the first time, and that's when I started hearing antiwar talk. Back then most libertarians were still entangled with conservatives through Young Americans for Freedom (YAF). So I heard lots of prowar talk also. I remember that when YAF prepared for its national conventions, two committees considered updates to its policy statement, one for domestic policy and one for foreign policy. Each time, as I recall, the domestic-policy committee called for abolition of the draft, while the foreign-policy committee strongly endorsed the draft and the Vietnam War. To jump ahead for a moment, at the 1969 national convention in St. Louis—the great showdown between the majority conservatives and minority libertarians—a guy got attacked for (legally) burning a copy of a draft card. (Brian Doherty reports on the incident in Radicals for Capitalism: A Free-Wheeling History of the Modern Libertarian Movement.) Thank goodness that was the end of the libertarian participation in the conservative movement.

The draft. That was the big, fat looming factor in our lives. You'd better get into college, or you'll find yourself on the way to an induction center with the next stop Vietnam. Once I entered college, in September 1967 (Temple University in my hometown, Philadelphia), I had Vietnam on my mind more often. The protests were in full swing. The Cold War propaganda I'd absorbed in earlier years was being erased by my encounters, both in person and in writing, with the likes of Murray Rothbard, Leonard Liggio, Karl Hess, Roy Childs, and others. They helped me make sense of the traditional leftist critique of the war. I now had an ideological reason to refuse to be part of that criminal operation, aside from simply not wanting to die over there. (Like Dick Cheney, who got multiple grad-school deferments from the Vietnam draft, I had "other priorities.")

At one point I sought counseling about conscientious-objector status from the American Friends Service Committee. I always enjoyed sitting down with the bearded guy in an army jacket who explained the application process to me. The antiwar culture was comforting; I felt at home. I remember filling out the paperwork, though I was pessimistic I'd ever be granted CO status. Back then your antiwar convictions had to be part of the tradition of a recognized religion. By that time I had no religion, no god. (The rules have since changed. In theory, members of the armed forces can apply for discharge as COs on nonreligious moral grounds.)

In my senior year I had a job interview with a newspaper in Ohio; I wanted to be a reporter. The interview went well, but the editor told me that until I was clear of the draft he could not offer me the job. That drove the point home. My future was shrouded in uncertainty because the state claimed the authority to seize me and send me thousands of miles away, where I would be ordered to kill perfect strangers who never even threatened to do me, my family, or my friends any harm.

One day I got a letter from the local draft board ordering me to report for a physical exam. Now this was getting a little too close for comfort. The abstract was becoming concrete. I duly reported for what would be the most depressing and humiliating day of my life. But I went in with a strategy. First, I had my doctor write a note explaining that I had severe hay fever, a condition that would make me a "liability" to the armed forces. (I had hay fever but it was not exactly severe.) Second, my parents knew a civilian doctor who helped administer physicals for the draft board, so I planned to position myself in order to present my doctor's note to him. I guess I was supposed to mention who my parents were, and that would prompt him to give me a medical deferment.

Things did not work out as planned. After I-don't-know-how-many hours of being poked and probed while in my skivvies by authoritarian army medical personnel, I looked at the several doctors in white coats who were ready to hear our excuses for why we should not be classified 1-A. Unfortunately, none of them looked like the doctor my parents knew, and I saw no name plates. Now what? I picked the oldest one, thinking that must be him. (It wasn't. He apparently wasn't on duty that day.) I sat down at his desk and gave him my note. He looked it over, showing no recognition of my last name.

"Well," he said, "I'm going to need more information from your doctor, such as the date of your last allergy attack and what medication you took."

My heart sank. I'll have to come back to this place?

But then he interrupted himself, stood up, and left the room. When he came back a few minutes later he said, "We get contradictory instructions every day. This [note] is fine."

Then he added, "This morning your blood pressure was high. We're supposed to take it again now, but I'll leave it as high."

He classified me 1-Y (not the more preferred 4-F: "Registrant not acceptable for military service"). 1-Y meant:

Registrant available for military service, but qualified only in case of war or national emergency. Usually given to registrants with medical conditions that were limiting but not disabling (examples: high blood pressure, mild muscular or skeletal injuries or disorders, skin disorders, severe allergies, etc.).

He could have entered an expiration date, requiring me to have another physical, but he left that space blank.

I was free! What had been the bleakest day of my life ended as one of the most joyous. I don't know who that doctor was or why he did what he did. But I will always be grateful.

So, yes, I dodged the draft and avoided Vietnam. Do I regret it? You've got to be kidding! Amazingly, some members of my generation say they do regret it. I recall that a couple of journalists associated with Charles Peters's neoliberal Washington Monthly wrote articles lamenting that they had ducked out of their generation's greatest challenge and confessing that this shirking of responsibility haunted them. After all, they wrote, their fathers rose to their challenge, World War II. How could their fathers' sons hold their heads high knowing that when the heat was on they found shelter in the safety of a college campus?

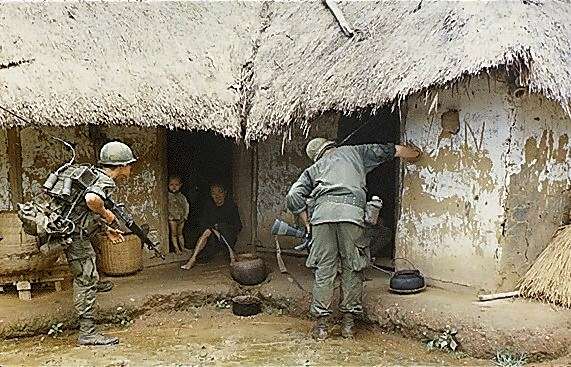

I don't understand that view at all. Vietnam doesn't deserve to be called a generation's great challenge. It was a criminal war of aggression waged against innocent people by American politicians and bureaucrats without an trace of honor or decency. Millions of Indochinese people were murdered. Nearly 60,000 Americans died. The blood stains on America will never be washed off.

If anything, avoiding that war was a moral duty. Thank goodness I was able to avoid it.

This column originally appeared at Free Association

Show Comments (418)