Arkansas Governor Wants Religious Freedom Bill Closer to Federal Law

Why shouldn't RFRAs apply to private lawsuits?

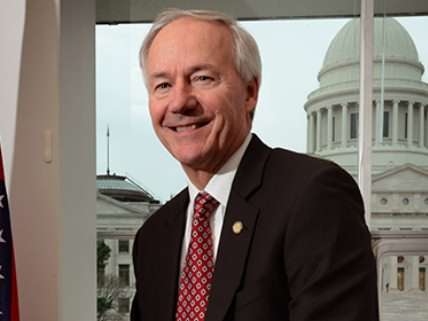

Yesterday, as Indiana Gov. Mike Pence promised to amend his state's newly minted Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) to clarify that the law "does not give anyone a license to deny services to gay and lesbian couples," the Arkansas legislature approved a similar bill. Although Gov. Asa Hutchinson said he would sign the bill if it "reaches my desk in similar form as to what has been passed in 20 other states," today he said it was not similar enough to the federal version of RFRA and sent it back to the legislature for changes. "We wanted to have it crafted similar to what is at the federal level," Hutchinson said. "To do that, though, changes need to be made. The bill that is on my desk at the present time does not precisely mirror the federal law."

Perhaps the most consequential way in which the Arkansas bill differs from the federal RFRA is that it explicitly applies to proceedings in which the government is not a party, which would include discrimination complaints. The RFRAs adopted by Indiana and Texas, which Hutchinson before today seemed to consider essentially the same as those in the 18 other states with RFRAs, have the same provision. Should it be a deal breaker?

John DiPippa, a University of Arkansas at Little Rock law professor who testified in favor of a narrower Arkansas bill, seems to thinks so. DiPippa told The New York Times he "certainly never anticipated it applying to actions outside of government." But if two men or two women try to compel a recalcitrant photographer to take pictures at their wedding (or try to punish him for refusing to do so) by filing a complaint under a local or state anti-discrimination law, is that really an "action outside of government"? The complaint is possible only because the government has decreed that businesses may not consider sexual orientation in deciding which customers they will serve, and the penalties for violating that rule are enforceable only through the government's courts. Surely this is a kind of government action, albeit one initiated by a private party.

That logic helps explain why most of the circuit courts to consider the issue have ruled that the federal RFRA, which does not explicitly cover proceedings brought by private parties, nevertheless can be applied to them—a position that also has been endorsed by the Justice Department. As Josh Blackman, a constitutional law professor at the South Texas College of Law, points out in a recent National Review article, lawsuits in which courts have allowed RFRA defenses include copyright and bankruptcy cases as well as discrimination complaints under Title VII and the Americans With Disabilities Act. Blackman notes that "the state courts, like the federal courts, have wrestled over whether state RFRAs can be raised as a defense in private suits."

Raising the defense and winning are two different things, of course. As I noted yesterday, University of Virginia law professor Douglas Laycock, an expert on religious liberty who supports gay marriage but is sympathetic to the claims of conscientious objectors who do not want to facilitate it, is "not optimistic" that Indiana's law will shield photographers, florists, bakers, and other business owners who decline work for gay weddings in the three Indiana cities—Indianapolis, Bloomington, and South Bend—that ban discrimination based on sexual orientation. Courts may very well decide that the burden imposed on people with religious objections to gay weddings is justified by the "compelling governmental interest" in preventing discrimination. Laycock notes that "nobody has ever won a religious exemption from a discrimination law under a RFRA standard."

The uncertainty about whether a RFRA defense can work in such cases gives cover to Pence, who says he wants to sign legislation this week that makes it clear "this law does not give businesses the right to deny services to anyone." Strictly speaking, RFRA guarantees no such right; it merely provides a possible defense in certain discrimination cases. Furthermore, Indiana law does not ban discrimination based on sexual orientation, so in most of the state business owners already have "a license to deny services to gay and lesbian couples." Since Pence has said he does not want to ban discrimination based on sexual orientation at the state level, the most the "fix" he has in mind could accomplish is to let gay couples in Indianapolis, Bloomington, and South Bend conscript unwilling contractors into helping with their weddings. That sort of forced tolerance does not strike me as a noble cause, and allowing it will surely alienate the conservatives who supported Indiana's RFRA.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Oh, phew. It had been almost 10 minutes since I heard anyone mention the RFRA.

"It will get out of control and we'll be lucky to live through it."

+1 Crazy Ivan

Did you know if you pronounce RFRA phoentically you sound like you're imitiating a dog?

LOL

And I'll bet a non-trivial number of folks think it's the same as RKBA.

A number of trivial people.

Six and a half of one, ...

5.5 of the other?

Close enough. /engineer

You know who else can be described as trivial people...

Alex Trebek?

It looks like this episode of Kulturkampf is bigger than Susan G. Komen/Planned Parenthood. But is it bigger than the 9/11 Mosque?

I just hope it involves death threats on Twitter directed at whoever started this whole mess so certain posters can accuse their opponents of psychopathy for supporting one side over the other.

shitstirrer!

amend his state's newly minted Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) to clarify that the law "does not give anyone a license to deny services to gay and lesbian couples,"

Well, that will be an interesting Establishment Clause case.

The statute will say, I guess, that nobody is required to violate their religious beliefs, unless its a gay person asking them to do so. Then they totally will.

That reads to me like a statute that specifically burdens/favors certain religious beliefs over others. The state will protect certain religious beliefs (that don't impinge on gays), while burdening others (that do impinge on gays).

Which would be a pretty clear violation of the Establishment Clause, distinct from having no RFRA at all and going with the baseline content-neutral "laws of general applicability apply regardless of religious belief".

It's not going to say anything about gays. It's just going to say the RFRA doesn't allow anyone to discriminate and violate public accommodation laws.

So, pretty much an exception that will consume the rule.

They're in such a frenzy to placate the SJW mobs on this one, I wouldn't be surprised if they did it the way I describe.

But they'll probably do it the way you describe. Which actually may set up a similar Establishment Clause issue - why is the state protecting some religious beliefs but not others is still a viable question, just not quite as pointed.

Laycock, an expert on religious liberty who supports gay marriage

You can't fool *me*, Jacob. That's from The Onion.

So the words can be the same but the intentions will be different.

Problem solved! Maybe with an "I'm sorry if this RFRA offends anyone." the whole issue will go away.

That's a fairly precise summary of the Politifact article detailing the differences between the Indiana law and the federal one.

They sold this wrong by saying it was about religious freedom. If the proponents had said it's absurd for someone to be fined thousands of dollars for refusing to sell flowers or a cake, I think there would be less controversy.

They say they oppose discrimination, yet that is exactly what the law allows- the right to refuse to do business with someone.

In other news, the KKK won their case against a baker who refused to make a cake for them:

I agree that if they can discriminate, she should be able to discriminate. Everyone, even bigots, should be treated equally before the law. The problem is a lot of people think it should be OK to discriminate against uncool people.

http://tribuneherald.net/2013/.....imination/

Principals...

Boo hoo, moron. So what's wrong with a Christian not wanting to serve a gay person based on their sinful lifestyle?

Oh that's right- because fundy Christians and KKK members are uncool.

Bigot is not a protected class!!!

/proglodyte

It's not that public accommodation laws are an abomination to liberty...

It's just that we haven't tweaked them just right so they only hurt the people we don't like.

I'm going out on a limb and say this is a parody article.

One of the other articles is entitled "Agents raid hair-dresser's home over bad haircut, find marijuana"

Many wonder that if she had simply lied about her reasoning, would this have even been an issue. That leaves the question to the public, do they want discrimination to happen out in the open where people can pinpoint it, or do they want it to operate a cloaked manner where it happens but it's hard to tell who is doing it?

Uh... doing it under other guises rather deliberately nullifies the public's input on the question.

The problem is a lot of people think it should be OK to discriminate against uncool people.

Like USAA Auto Insurance?

Wait...what?

*fumbles around for USAA number*

Is this for real. Because if it is I'm having visions of proggy heads exploding all across the country. If not, then this is a cruel April fools joke.

It's not real.

"for satirical purposes"

Oopsy!

"If they can discriminate against people, then surely I cannot be forced to support their beliefs by providing them services against my will."

Well, there you go. The notion of having a sexual orientation is inherently a form of discrimination, based on either sex or gender.

Indiana Gov. Mike Pence promised to amend his state's newly minted Religious Freedom Restoration Act

He should be criticized for trying to execute a power he doesn't have. The legislature is the only body that can amend legislation, all Pence can do is accept or veto.

But becoming a dictator with unilateral powers signals well to progs.

Illinois has an "amendatory veto" where the guv sneds something back changes, and it will stand unless they over-ride.

amend his state's newly minted Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) to clarify that the law "does not give anyone a license to deny services to gay and lesbian couples,"

Then what was the point of this shitshow? I mean, other than to raise a culture war flag?

As if any other point was necessary.

Well, there's still the abortion issue.

Off topic, but does here is a post from Salon about Patton Oswalt making fun of over sensitivity.

http://www.salon.com/2015/04/0.....socialflow

...filing a complaint under a local or state anti-discrimination law, is that really an "action outside of government"?

Well, let's not go splitting hairs here. With the criminal code and regulatory environment what it is, government is literally a part of every single act you undertake. So nothing really happens outside government. I mean, did you really think you built that?

The original RFRA didn't specifically say, "this applies when a private party seeks to invoke government authority against a religious objector."

All the law said was that it restricts "Government" from abridging religious freedom, and the *only exception* is if there's a compelling interest which can't be satisfied in any other way.

To say that "government" doesn't mean a court or government agency acting on the behest of a private party, could result in this scenario: A neighbor files a public-nuisance suit trying to close down a Rastafarian church - because dope - the court can close down the church without regard to religious freedom.

Progs will then protest that this is racist and suppresses a cool non-Christian religion, and they'll yammer on about conservative repression.

My ex-wife makes $75 every hour on the laptop . She has been laid off for seven months but last month her pay check was $18875 just working on the laptop for a few hours.

Look At This. ???? http://www.jobsfish.com

I had a short discussion today with a gal friend about this law. He's very open-minded (probably being a gay Catholic will do that to you) and is very willing to have an actual discussion about the principle of free association and its consequences. I need to get together with him more often. He's the only one of my progtard friends who presents factual information, instead of emotional garbage, into his arguments.

Gal friend = gay friend. Jeezus.

He's the only one of my progtard friends who presents factual information,

Oh, so he's mansplaining. Maybe gaysplaining?

Amendment XIII

--------------- ---------------- ------------ ---------------- -------------- -------------- -------------------

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

--------------- ---------------- ------------ ---------------- -------------- -------------- -------------------

Section 3. This shall not prohibit the requirement for vendors to provide service for homosexual marriajus*.

.

.

.

.

.

.* marriajus is the term this writer used to describe life-long monogamous commitments of homosexuals

Discrimination is only 'allowed' more and more if you subscribe to an Establishment brand of mystical bullshit.

What about Trekkers not serving Yoda at the comic-book shop?