Tom Cotton: I Said 'replacement with a pro-western regime,' not Pre-Emptive War!

Hawkish senator disputes characterization of his interventionist views toward Iran

In a March 11 post about Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.), titled "GOP's New Foreign Policy Hero Is a Surveillance-Loving Interventionist Nightmare," I listed among the freshman senator's policy positions that

the U.S. should pre-emptively invade Iran, topple the mullahs, and ensure "replacement with [a] pro-western regime."

Cotton's office emailed asking for a correction, saying that the senator has never said anything explicitly about pre-emptively invading Iran. After reviewing and transcribing the source material for my claim—a Feb. 26 panel at the Conservative Political Action Conference titled "When Should America Go to War," which I attended—I have concluded (updating the piece accordingly) that Team Cotton is in the right: He did not explicitly say America should pre-emptively invade Iran. As an avowed literalist, I apologize.

What Cotton did say was that "The fundamental American policy towards Iran now, in the future, as well as in the past should be regime change," that "Whatever happens in these negotiations, the policy towards Iran has to be regime change, and the replacement with a pro-western regime that is not going to be the greatest force of instability and greatest state sponsor of terrorism in that region," that the current Iranian regime has "been exporting terror and killing Americans around the world for 35 years," and that on the general question of "When would we be going to war," the answer includes when "our people are attacked" and "when we have transnational terrorist groups…operating in lawless safe havens."

So how on earth did I get the impression that Cotton advocates attacking Iran?

The answer, I think, is more interesting than parsing the seemingly proactive properties of the word replacement, or taking a walk through the history of U.S. politicians fantasizing about a pro-western regime in Tehran. Cotton truly believes, as he stressed at the CPAC panel (which you can watch and judge for yourself here), that "The best way to avoid a war…is to be prepared to fight a war, and then to be willing to fight a war." The preparation part involves "substantial increases in spending on our defense," but what about the willingness piece? Let's quote a longer chunk of Cotton's thinking:

[Y]ou also sometimes face a world where deterrence breaks down. And the world has to know we are willing to go to war. That's both our allies and our enemies. Regrettably, right now many people around the world don't believe that our president is willing to go to war.

When would we be going to war? To defend our core national security interests, when our our territory and our people are attacked, as they were in World War II at Pearl Harbor, as they were on 9/11 in New York and…in Virginia and in Pennsylvania. When our allies are invaded, as happened in Kuwait, when Saddam Hussein crossed an international border and threatened more allies in the region as well. When we have transnational terrorist groups like the Islamic State operating in lawless safe havens, like Syria, Iraq, [unintelligible] Libya and elsewhere. Like Al Qaeda did in Afghanistan in the years before the 9/11 attacks.

At minimum, if we are to take those words seriously, that's a recipe for a whole lot more war in the here and now: against ISIS in Iraq and Syria and perhaps Lebanon; probably against Al Qaeda in the Arab Peninsula in Yemen; arguably against bad guys controlling various safe havens within Sudan, Somalia, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Hezbollah, to name one organization in the news, is a "transnational terrorist group" that shares at least some commonalities with ISIS.

Cotton sees American readiness to take up arms as an essential deterrent: "If we are willing to fight a war, if we're prepared to fight a war, then war is much less likely to occur." His go-to historical analogy, to the surprise of no one paying attention to conservative interventionism, is the weak 1930s response to the rise of Hitler. But it's hard to fathom how that insight translates to, say, the Taliban in Afghanistan—do we just need to fight them longer, and nation-build them better, only this time not get tired of the effort? Would a more convincing willingness by the Great Satan to robustly go after AQAP in Yemen deter that or any other Islamist group from acting terribly and against American interests? Or would this increased willingness to go to war lead to more war?

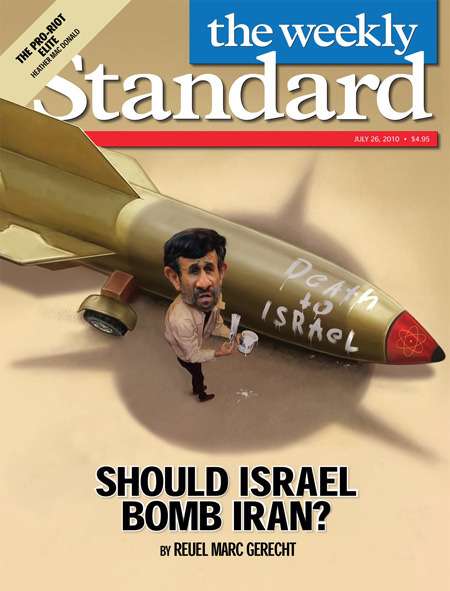

You of course can have an official policy of "regime change" that does not involve pre-emptive war. That's in fact what America had toward Baghdad after the 1998 Iraq Liberation Act, a law championed by Cotton's chief intellectual sponsor, William Kristol. How were we supposed to achieve this goal? Through a familiar-sounding cocktail of economic sanctions, weapons inspections, credible threats and use of force, and assistance to dissident groups. So how did that story end?

With pre-emptive, ill-advised war (which Cotton said at the CPAC was still in hindsight "the right decision"). Even with all that American sacrifice, the existence of a "pro-western regime" in Baghdad is tenuous at best.

So I asked Cotton's Communication Director, Caroline Rabbitt,

[D]oes Sen. Cotton believe that a hypothetical tighter international economic sanctions regime, backed with the credible threat of U.S. force where appropriate, will be sufficient to bring about "replacement with a pro-western regime that is not going to be the greatest force of instability and greatest state sponsor of terrorism in that region"? If so, I wonder if he has any reflections as to why sanctions/enforcement failed in that regard with Iraq?

She responded:

I appreciate you sending along those hypothetical scenario questions, but perhaps you should have sent those before you published an inaccurate statement.

I earned that.

I believe that the practical effects of Cotton's foreign policy would almost certainly lead to pre-emptive war; that the Kristolian pool he swims in is filled with those openly pining for pre-emptive war; that one of the biggest beneficiaries of conservative interventionism has been the very mullahs they all find so distasteful; and that nobody I've seen on the neoconservative side has ever convincingly thought through the problem of long-term American public disaffection with open-ended overseas military engagement precipitated by a promiscuous willingness to threaten force. Libertarians are hardly the only political cohort whose foreign policy views need to get real.

Show Comments (106)