Killer or Artist?

Prosecutors' use of rap lyrics as evidence is chilling artistic speech.

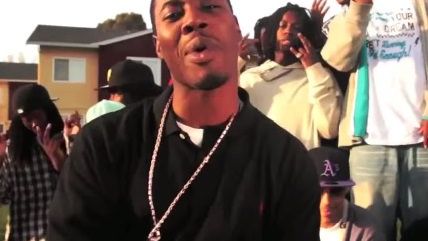

When Laz Tha Boy threatens to murder someone, it may seem scary. He proudly mimes shooting handguns at the camera and promises to "leave a…face burgundy." But does the stylized, menacing content of rap videos have a place in a courtroom?

Deandre Mitchell is from Richmond, California. He writes many types of music but found local success in the Northern California area as a gangsta rapper. Laz Tha Boy is his rap persona.

"It's supposed to be freedom of speech. So when I use my freedom of speech and voice my opinion then you all turn around and try and use it against me like this is who I am as a person," Mitchell said in July 2014 from behind a pane of glass at a detention facility in Martinez, California. At the time, he had been confined there for two years.

Three of Mitchell's rap videos ("What You Do It Fo," "It's Real," and "Southside Richmond") were used as evidence against him in 2012, when a grand jury indicted him on two counts of attempted murder. Even though Laz Tha Boy's videos were made years earlier and didn't include references to the shootings at the heart of the indictment, Satish Jallepalli, a prosecutor with the Contra Costa County District Attorney's Office, says they illustrate Mitchell had the mind-set to commit such crimes.

"At the end of the day, yes, a person has a First Amendment right to speak," Jallepalli says, "but when they commit a crime, sometimes what they say will end up being used against them."

In the grand jury proceeding, Jallepalli pointed to violent lyrics like "If I see him I'm gonna murk 'em."

"The term murk [is one] rappers use all of the time," explains Charis Kubrin, an associate professor of criminology, law, and society at the University of California, Irvine. "If it's not murk, it's 'I'm gonna smoke him,' 'I'm going to pop a cap in him.'" Kubrin is a co-author of the paper "Rap on Trial," published in the journal Race and Justice, which details the history and scope of hip-hop in criminal proceedings. She says prosecutors understand the powerful effect such lyrics can have on jurors.

"If you think about who is serving in our jury system in the United States, it's typically older, higher socioeconomic status, typically white. They often don't have the proper context for understanding rap music," Kubrin says.

The tactic dates to the 1990s, but its prevalence has increased lately as prosecutors share how successful it can be. In 2004, Alan Jackson, a former gang prosecutor in Los Angeles, wrote in a guide for the American Prosecutors Research Institute that "through photographs, letters, notes, and even music lyrics, prosecutors can invade and exploit the defendant's true personality."

John Hamasaki, Mitchell's attorney, says the use of rap videos and lyrics in the Mitchell indictment may have blinded jurors to the lack of physical evidence. In the end, the eyewitness testimony of the intended victim, who said Mitchell was involved in both attempts on his life, fell apart when he admitted his claims were "based on rumors I had heard." In August 2014 the witness signed a statement saying, "I never saw Deandre Mitchell during either of the shootings."

Because Mitchell was facing a life sentence, he accepted a deal on November 5, 2014, pleading no contest to one count of assault with a firearm, and was released. But the possibility that their lyrics could be used against them during criminal proceedings continues to chill aspiring rappers across the United States.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Killer or Artist?."

Show Comments (19)