The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Law faculty productivity over time

It's generally understood that faculty productivity declines over time. The common wisdom is that professors write up a storm to get tenure; they then write somewhat less mid-career; and they don't do much writing at all when they are senior. There has been some study of this dynamic in the sciences. As far as I know, however, this pattern hasn't actually been measured at law schools. I recently decided to measure it at my own law school, George Washington University. The results really surprised me, as they suggested no change in productivity over time.

First, the methodology. The GW Law website has a listing of faculty publications, with associated page lengths, for each faculty member. I tasked a research assistant with tabulating the publication dates of every article, individual book chapter in an edited volume, and book review that each tenured professor published. A work had to be at least 10 pages long to count, a limitation I imposed to try to exclude magazine articles and short bar journal pieces that could skew the data and that some professors had listed as publications. I also decided to exclude books, as they proved too hard to count. To see the problem, imagine a professor writes a casebook with annual supplements that has gone through eight editions over 30 years. How many publications do you count? 1? 8? 38? It's hard to say, so I limited the study to articles, individual book chapters in edited volumes, and book reviews.

My research assistant then looked up the year that each professor began tenure-track teaching, whether at GW or another school. We used that start date for each professor to determine each professor's article productivity over time in five-year bands starting from when they began the tenure track. To make the data presentable, we grouped the faculty in cohorts based on five-year windows of how long they have been on a law faculty since they began the tenure track. The most junior group had taught 5-9 years; the next group 10-14 years; the next group 15-19 years, etc. The most senior group had 40+ years of teaching. The total number of professors in each group, starting with the most junior, was 4, 10, 13, 12, 7, 5, 5, and 4. We excluded GW's one tenure-track professor, as she had not yet taught for five years.

This methodology allowed us to chart faculty productivity over time in three slightly different ways. First, we can see how productivity changed over time for the faculty as a whole; second, we can see the changes within each cohort over time; and third, we can compare productivity of different cohorts at the same stage of their careers.

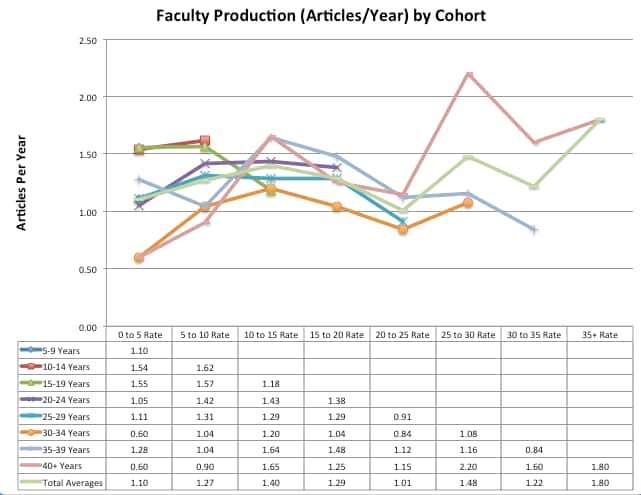

The chart below shows the results. The vertical axis is the average number of published articles per year, and the horizontal axis represents five-year bands of time starting at the beginning of each professor's career and moving on over time.

The most surprising result is that there is no obvious downward trend. Faculty productivity didn't decline over time. If productivity dropped, you would expect the lines to slope downwards. But they don't. For the most part, the lines seem to show random variations rather than a consistent upward or downward trend. Looking at the raw data, I saw a lot of variation within each cohort. Some professors wrote often, while others wrote very rarely. But the overall productivity did not seem to decline. Perhaps the easiest way to see that is to follow the light green line that is more or less at the center of the lines. That's the line that combines all the faculty that have completed that period of service. No downward trend.

I was also somewhat surprised that there wasn't much variation in productivity cohort-to-cohort. There's a common belief that younger professors write a lot more than senior professors did. But at least in the case of GW, that wasn't the case. I suspect there would be significant differences in the number of articles professors wrote before they started the tenure track. These days, to get a job, you need to write more than before to get the job. But it appears that once folks started the tenure track, the numbers from generation to generation didn't show an obvious trend towards more writing.

Let me add a bunch of important caveats. First, the numbers we're talking about are pretty small. I studied only one faculty, with 60 tenured professors, and the individual cohorts ranged from only 4 to 13 people. I don't know if you would get the same results at other schools, or with large groupings of faculties.

Second, tabulating productivity and start dates for each professor was itself somewhat complicated. The list of publications on the GW homepage may be incomplete in some cases. A few publication pages were missing entirely, and a count of articles of sufficient length available on Westlaw was used instead. Determining when a person began the tenure track sometimes required some educated guesswork, too, even using the AALS book. I looked over this data briefly to see if I could spot errors based on colleagues I know well, but I didn't double-check start dates with my colleagues.

Third, my methodology was of course imperfect, so for any given case the numbers may or may not accurately reflect productivity. I could have measured productivity differently, such as by pages written, or I could have treated co-authored articles as only being half an article. I didn't. As a result, a professor who publishes five co-authored case summaries every year, each 11 pages long, would be recorded as extremely productive, while a professor who writes five books a year would not be. Given these limitations, the numbers are useful (if they are useful at all) only in the aggregate.

Finally, we can't rule out explanations for the data that that are consistent with an overall story of declining productivity. For example, perhaps lateral hiring counters declining productivity. Lateral hires are usually quite productive, so perhaps "home grown" professors decline in productivity on average but the overall numbers are boosted by incoming laterals. Also, perhaps professors begin with major tenure articles early in their careers but later shift to writing shorter (but still 10-page long) symposium articles and book chapters. In that case, the publication rate could stay constant but the significance of the works would decline. Both are possibilities. On the other hand, we can tell the opposite story, too. Perhaps professors start writing articles but then turned to books, which my study didn't count. It's hard to say.

Show Comments (0)