After Copenhagen: The Myth of Civilized Censorship

Hate speech laws legitimize violence against those who offend

The two recent acts of censorship-by-murder in Europe—first at the offices of Charlie Hebdo in Paris, and then at a free-speech debate in Copenhagen—have put the continent's political classes in a pickle.

For as much as European rulers want to, and do, condemn the brutal actions of these Koran-thumping offense-takers, the fact is they also share something in common with them: a devotion to shushing and sometimes punishing those who offend people's sensibilities.

There's only so much distance the elites of Europe can make between themselves and these cartoonist-loathing shooters. For while our elites might not summarily execute people for the crime of being offensive, they do arrest them, and put them on trial, and occasionally jail them. All of which are acts tinged with menace, underpinned by the threat of violence, where it's understood by all that if any of these offense-givers were to dodge arrest or jump jail they could be restrained by force. It isn't only Islamo-censors who use violence to silence—all censorship, by its nature, is violent.

The awkward fact of a shared outlook between the opinion-forming set and the killers of cartoonists surfaced once again following the shoot-up of a debate about Islam and free speech in Copenhagen at the weekend.

The smoke from the gunfire had barely disappeared before cagey columnists were saying that if we don't want to get killed then we should stop offending people. A writer for the Guardian said Copenhagen should remind us of the "obligations…upon those who wish to live in peaceful, reasonably harmonious societies"—primarily the obligation to "guard against the understandable temptation to be provocative," especially by publishing Muhammad-mocking cartoons. Shorter version: to avoid being shot, zip your lip. The Guardian writer is effectively doing the shooter's dirty work for him, spelling out in words what the shooter said with bullets: if you offend, you might die, so don't do it.

Another Guardian columnist said the peoples of Scandinavia should now "step back from their principles"—their "strong belief in the moral imperative of free speech"—and "show more of the pragmatism for which Denmark is also famous." In short, Denmark and its neighbour nations should do what the shooter wanted them to: ditch that pesky principle of free speech, that old right to provoke, and instead erm and ahh before saying or showing anything edgy.

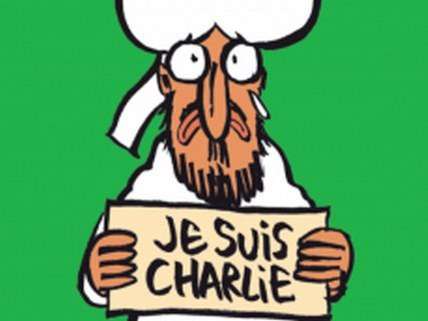

These responses to Copenhagen, this effective aiding and abetting of the shooters' profoundly illiberal message by the supposedly liberal commentariat, echo some of the grislier responses to the Charlie Hebdo massacre. There was the infamous Financial Times column that slammed the "editorial foolishness" of Charlie Hebdo (apparently the cartoonists brought their murders on themselves), and the New Statesman screed against "free-speech fundamentalists" who stupidly say "Je Suis Charlie" when the fact is we all know there are free-speech lines that "cannot be crossed." It sounded almost like a threat, an echo of the sentiments of the Charlie Hebdo killers themselves: "Cross the line and you'll regret it…"

So twice now, the great and the good have condemned the actions of offense-killing gunmen while at the same time embracing and spreading the moral message behind these actions: the idea that there's a line that shouldn't be crossed, things that shouldn't be said, and principles that should now be ditched. In essence, liberal observers have made themselves willing participants in acts of terror, behaving as the propagandistic spokespeople, or at least as media echoers, for the misanthropic, intolerant, censorious killers.

These creepy commonalities between small gangs of killers and whole layers of respectable society reveal that these attacks may not be as alien to our way of life as some would have us believe. In fact, the two shooting sprees can be seen as simply a bloodier expression of something that's now depressingly mainstream in Europe: the idea that it's bad to give offense—so bad that you can be punished for doing it.

The massacre at Charlie Hebdo and the shooting in Denmark didn't happen in a vacuum; they happened at a time and on a continent where offensiveness is an actually punishable offense.

So in France in the six weeks since the Charlie Hebdo massacre, far-right ideologues have been arrested for the crime of anti-Semitic speech, and three people who wrote homophobic tweets have been convicted of committing a hate crime. In Copenhagen just four months ago, an art exhibition was cancelled on the basis that it was racist: the Danish penal code forbids any speech that threatens or simply insults or degrades a group on the basis of its race, ethnic origin, sexual orientation, or faith. Was it the Koran that gave the Copenhagen cafe shooter the idea that any slur against his faith was an intolerable crime, or was it the insult-punishing law of the land in which he was born and brought up? His own nation sent him the message that anyone who degraded his faith deserved to be punished.

Across Europe, a glut of hate-speech laws now control what people can say and write. Over the past 30 years, everywhere from Britain to France to Finland, laws have been passed forbidding the insulting or ridiculing of religious folk, women, ethnic minorities, gays, and others. These laws don't only punish those who shout the word "Nigger!" or "Faggot!", which would be bad enough; they punish people for their actual moral and political convictions.

Like the Swedish pastor given a one-month suspended prison sentence for expressing his belief that homosexuality is a "tumour" on society. Or Brigitte Bardot, arrested and fined five times in France for describing Islam as barbaric. Or the novelist Michel Houellebecq, dragged to court in France for describing Islam as "the stupidest religion." Or the far-right British politician given a suspended eight-month prison sentence for expressing his disdain for Britain's immigration policy and using the word "darkie" to describe foreigners. Or the Swedish artist sent to jail for six months for producing paintings that mocked black people.

It's the return of the mindset of the Inquisition, of the old, rotten idea that those who offend orthodoxies, in this case PC, may be punished, sometimes severely. Maybe the Charlie Hebdo and Copenhagen killers were mind-warped by the online ravings of some extremist finger-wagging imam from the Middle East—or maybe they imbibed the thinking of their own societies, of the laws in France and Denmark, which remove the liberties of those who insult Muslims and other groups, and turns these insulters into criminals, outcasts, moral lepers. These killers can be seen, not so much as an invading foreign strain of intolerant Islamism, but as the militant enforcers of the now mainstream European creed of offense-avoidance and criminalization of hate and ridicule.

Some will say: "But our censorship is more civilized than theirs. We don't kill, we just arrest and fine or imprison those who misspeak or misthink." Please. What underpins the state's ability to criminalize and in some cases incarcerate those who give offence? Force does; violence does; it's the knowledge that anyone who refused to pay his fine or serve his prison sentence for the crime of saying what he thinks would be made to do so by the enforcers of the state's will. Censorship is inherently threatening. It is never civilized. In fact, it's the antithesis of civilization, for it calls into question the ability of the public to judge for itself which ideas are good and which are bad and it elevates, with menace, tiny cliques of people into the arbiters of what may be thought and said.

To rebuild freedom in Europe, it isn't enough condemn the actions of small groups of gunmen. We must also dismantle, piece by piece, the vast legal structures and censorious culture that empower the offense-takers, making them believe they have the right to silence and punish those who criticize them and to live in a safe space, an anti-social bubble, in which a cross word is never uttered. Let's invade their safe space. Let's burst their bubble. Let's challenge the idea that words of any kind—be they gratuitously offensive or just morally dubious—should be the business of either the state or Islamo-murderers.

Show Comments (243)