Fight Poverty—Use Fossil Fuels

Review of "The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels"

The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels, by Alex Epstein, Portfolio/Penguin, 248 pp., $27.95.

The climate crisis, Al Gore declared in 2007, is "not a political issue, it's a moral issue." It's "a clear moral issue," the climatologist James Hansen said in 2011. "We should think of global warming in a different way—as the great moral crisis of our time," the environmentalist Bill McKibben wrote in 2001.

What has provoked this great moral crisis? Chiefly the burning of fossil fuels, which is increasing the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere; if continued, most climatologists believe, this will significantly boost the average temperature of the globe. Many argue that this man-made global warming could produce catastrophic results, including widespread famines, flooded coastal cities, chaotic weather, and mass extinction. "Continuation of high fossil fuel emissions, given current knowledge of the consequences, would be an act of extraordinary witting intergenerational injustice," Hansen and his colleagues claimed in a December 2013 article for PLoS One.

Moralizers do not make trade-offs between right and wrong. When a person declares an activity a moral issue, he is not engaging in debate; he is ending debate. The only thing to do is to do the right thing. In this case, climate moralizers insist that the right thing to do is for the current generation to cut, drastically, its use of fossil fuels. If someone disagrees, he is not merely mistaken. He is evil.

In The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels, Alex Epstein aims to turn this moral argument on its head. Epstein, the founder of the Center for Industrial Progress, makes a persuasive case that cheap and abundant fossil fuels are critical to enabling billions to escape conditions of Malthusian privation. But the core debate here isn't really moral so much as it's practical; a debate based on weighing the risks of poverty against the risks of climate change.

Epstein starts by asking, "By what standard or measure are we saying something is good or bad, great or catastrophic, right or wrong, moral or immoral?" People like McKibben, he argues, elevate the moral value of nature over that of human beings. As a result, they believe that "there is something inherently wrong with man having an impact on the climate," and that our impact on the natural environment in general should be minimized.

One of the more disturbing examples that Epstein cites comes from the National Park Service biologist David Graber, who in 1989 wrote: "We have become a plague upon ourselves and upon the Earth. It is cosmically unlikely that the developed world will choose to end its orgy of fossil-fuel consumption, and the Third World its suicidal consumption of landscape. Until such time as Homo sapiens should decide to rejoin nature, some of us can only hope for the right virus to come along." Wishing a plague would wipe out most of humanity is near the absolute height of immorality.

"To me," Epstein counters, "the question of what to do about fossil fuels and any other moral issue comes down to: What will promote human life? What will promote human flourishing—realizing the full potential of life?" Much of the rest of the book explores the manifold ways that energy derived from coal, oil, and natural gas has enabled human flourishing over the past two centuries.

As humanity burned more fossil fuels and increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, human lives dramatically improved. "Weather, climate, and climate change matter—but not nearly as much as they used to, thanks to technology," Epstein writes. For example, the death rate from extreme weather events has dropped 98 percent since 1920. Indeed, the chief benefit of burning fossil fuels has been longer and healthier human lives. The central idea of Epstein's book is that "more energy means more ability to improve our lives; less energy mean less ability—more helplessness, more suffering, and more death."

Before the Industrial Revolution, human societies were mainly powered by human muscles. The average person burns 2,000 calories per day. A gallon of gasoline contains 31,000 calories, the amount energy a human body burns in 15 days. The machines that Americans use every day to power their homes, commute, work, and play, consume about 186,000 calories per person—the equivalent of 93 human servants consuming 2,000 calories daily.

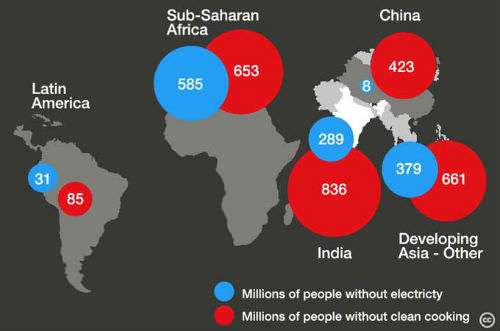

On the other hand, billions of human beings still rely on their muscles and on biomass such as wood and animal manure. In fact, some 1.3 billion of the world's 7 billion people do not have access to electricity; about 3 billion overall are classified as not having adequate access to electricity. These people need to be connected to modern energy sources in order to flourish. Global energy production would have to quadruple to raise the rest of the world to U.S. levels of consumption.

What would using more fossil fuels to fulfill this demand do to the climate? Epstein does not subscribe to the climatological consensus that boosting atmospheric carbon dioxide will produce dangerous climate change. Among other things, he points out that the climate computer models have so far predicted more warming than has actually occurred. But let's assume man-made warming anyway. That by itself does not tell people what are the best policies to handle it.

The climate moralists frequently argue that renewable energy will fix the problem. In December 2012, for example, McKibben gushed that "there were some days this month when [Germans] got half their energy from solar panels." The reality is that after spending $130 billion, Germany gets only 4.5 percent of its gross energy supplies from solar panels. Epstein characterizes the climate catastrophists' advocacy of current renewables as trying to force everyone to use the worst energy technologies while hoping for the best.

In a nice comparison of material use, Epstein reports that one megawatt of wind generation capacity requires 542.3 tons of steel, coal generation requires 35.3 tons, and natural gas requires 5.2 tons. Of biomass energy supplied by corn ethanol, he asks the devastating question, "Why should we feed human food to machines with hundreds of times our appetites?"

So Epstein is entirely correct when he asserts that current renewable energy technologies are far too costly and not scalable—that is, not capable of being easily expanded or upgraded on demand. But I suspect that he is underestimating human ingenuity when it comes to improving their efficiencies and lowering their costs. Epstein does note that one alternative to fossil fuels, nuclear power, is safe, reliable, and scalable. But he adds that nuclear energy is expensive compared to fossil fuels due to excessive regulations, which for Epstein makes it doubtful that we can roll out substantial supplies of nuclear energy in the near term.

He may be too glum about that. Environmentalist opposition to nuclear power may be abating. In November 2013, Hansen and his colleagues published an open letter to "those influencing environmental policy but opposed to nuclear power." It forthrightly states: "Renewables like wind and solar and biomass will certainly play roles in a future energy economy, but those energy sources cannot scale up fast enough to deliver cheap and reliable power at the scale the global economy requires. While it may be theoretically possible to stabilize the climate without nuclear power, in the real world there is no credible path to climate stabilization that does not include a substantial role for nuclear power."

Another interesting speculative possibility is that the engineers at Lockheed Martin who announced a design for a small-scale nuclear fusion reactor last fall will get it to work. At any rate, Epstein is right that "our concern for the future should not be running out of energy resources; it should be running out of the freedom to create energy resources, including our number-one energy resource today, fossil fuels."

There is another problem with Epstein's book, one more substantial than the possibility that he has unduly pessimistic about nuclear's political prospects. Is the energy and climate debate really an argument about morality, pitting those whose standard is a flourishing humanity against those whose standard is a burgeoning natural world?

Graber's wicked musings notwithstanding, it isn't necessarily so. Epstein acknowledges, after all, that "we do want to avoid transforming our environment in a way that harms us now or in the long run." And the climate change activists cited at the beginning of this article don't merely talk about the human impact on the environment; they talk about the environment's impact on humanity, saying they don't want to transform the climate in a way that harms future generations.

Deciding how best to enhance our descendants' prospects is not a clash over right and wrong. It is a dispute over trade-offs. Will loading up the atmosphere with greenhouse gases as we generate more innovation, knowledge, technology, and wealth yield more benefits than harms for us and for future generations?

Epstein is clearly right that supplying people, especially poor people in economically underdeveloped parts of the world, with cheap fossil fuel energy now will yield far more benefits than harms. What about future generations? Is the continued use of fossil fuels, as Hansen argues, an "act of extraordinary witting intergenerational injustice?" Not necessarily.

Based on scenarios devised for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, people living three generations hence with the worst consequences of climate change will still likely be more than eight times richer than people living today are. Without climate change, people in 2100 would supposedly be 10 times richer. It is really more just for people today with global average per capita incomes of $10,000 to sacrifice so that people living in 2100 will have average incomes of $100,000 instead of only $80,000?

There's yet another deep debate about values lurking beneath our climate arguments, one that Epstein largely ignores. Anti-market ideologues use catastrophic climate prophecies to attack an economic system they detest. In This Changes Everything, for example, activist Naomi Klein asserts, "Our economic system and our planetary system are now at war." Climate science, Klein claims, is "the most powerful argument against unfettered capitalism" ever. For writers like Klein, climate change is an excuse to remold the world. Call it the green shock doctrine.

Epstein concludes that "the moral case for fossil fuels is not about fossil fuels; it's the moral case for using cheap, plentiful, reliable energy to amplify our abilities to make the world a better place—a better place for human beings." His intriguing book strongly makes the case, moral or not, that increasing energy abundance in whatever form is crucial to enhancing the human prospect.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

In case anyone is interested, a couple of years ago Epstein and McKibben had a lively debate, with an audience who asked good and cogent questions. This is more of what is needed in the whole discussion. Both acquitted themselves well.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0_a9RP0J7PA#t=5674

Yes. That's exactly what it is. The logical conclusion of environmentalism is everyone living a sustainable lifestyle while only trading with people local to them. There's a word for that: poverty.

I think 'feudalism ' works too.

Having some watery tart throw a sword at you is no way to run an economy, son.

"Starvation" will do in not too long.

Well I didn't vote for you!

That sums it up and these asswipes pretend that they care about the impoverished in the third world. It's hilarious.

Otherwise known as "the gold standard," because the gold standard idea makes Malthusian assumptions which contradict the cornucopian assumptions of Bailey and Epstein.

What could ever be more morally superior than sacrificing billions of humans by plunging them into needlessly hellish, impoverished existences for the sole purpose of pleasing the high goddess Gaia?

The Earth is sustained only by the suffering of humans.

Based on scenarios devised for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Damn near choked to death laughing.

Human beings are a disease, a cancer of this planet.

In my naive youth, I thought that there was something insightful about that scene. Of course now I realize it is bullshit. The only reason most animals find an equilibrium with their environment is because their environment is good at killing them. And of course the societies that are best at co-existing with their environment are the wealthy ones.

It's funny how wealthy societies can afford to look after the environment. It's almost as if the environment would benefit from human prosperity. Nah. That's denier talk.

"The only reason most animals find an equilibrium with their environment is because their environment is good at killing them."

Any equilibrium is definitely short lived; it takes a certain ignorance to twaddle on about 'the balance of nature'.

'Equilibrium' is based on you living long enough to reproduce enough to sustain the species, and not any longer.

Dead by 30 is 'natural'.

Cumulus9

1/15/2015 9:00 PM CST [Edited]

And why is it necessary to eat so much meat, anyway? "Because I like it" or "it tastes good" are not real answers. Anyone who claims to be an environmentalist should not be eating meat. It's always inhumane to kill an animal. It takes far more water and energy and creates more waste than non-meat.

Why is the animal killing industry considered a nice family business? We need to send every grade school kid on a field trip to a slaughterhouse, pig farm, and chicken operation. People need to think about where this pink stuff actually comes from. I realize "think" might be a foreign concept for a lot of people.

From the comments section of the linked article.

And what's the deal with airline food anyway?

Something tells me that if we were to scrutinize Cumulus9's daily activities, we would find a lot of energy spent doing things that aren't "necessary".

Like posting on the internet.

This is why I always laugh at the ubiquitous Marxist/socialist trope that capitalism sustains itself by creating "false needs" in people, when they can never quite seem to stipulate any coherent criteria for what would qualify as a "real" need.

The "real" need is whatever they decide you need. If they don't personally like it then no one else could ever possibly like/want it either. Hence we seem them screaming "Ban it!" at the top of their lungs constantly.

Now granted there are differences between wants and needs. You want a Lambo but you don't need one. But if you've got the money and the desire for something, then who the fuck am I to tell you that you can't have it.

People need to think about where this pink stuff actually comes from.

People like Cumulus9 should be forced to skip 3 meals in a row. At thend of that time period, C9 will say "Fuck that chicken, i'm fucking hungry" and willingly eat raw chicken with feathers still attached. That is literally how long that form of 'civilization' holds up.

I've been through SERE training, I've seen it happen.

C9 also fails to see that plants are living organisms as well. I'm pretty sure that lettuce plant doesn't want you to uproot it and then chow down. And I do hope that when C9 craps after eating a vegetable that he/she does it outside so as to spread the seeds.

I'm almost positive that I learned somewhere that plants have defenses because they don't want you to fucking eat them. Damn, where did I learn that, oh yea, it was biology class and not fucking Disney cartoons.

I realize "think" might be a foreign concept for a lot of people.

The irony, it burns!!!!

I scanned this article and then started reading the comments. I had to quit before I went into a full on freak out rage. The stupidity of people when it comes to food and farming animals is staggering.

In regards to this article, if one really wants to save the environment then there needs to be an economic incentive to do so. For example, hunting and fishing are big business here in the U.S. Currently we have more deer and more ducks than we've ever counted before. Other animals are also growing such as elk, bear, beavers, coyotes, rabbits, squirrels, etc. Humans have an interest in these animals and their populations are stable/growing.

Currently the only thing being done about climate change is taxing everyone into submission. This will not work and may even lead to a lowering of living standards as it will kill private ingenuity, growth, and investment.

It's always inhumane to kill an animal. It takes far more water and energy and creates more waste than non-meat.

So it's inhumane to kill an animal, but it's also inhumane to spend so many resources on raising animals.

The animals sound fucked either way.

We need to send every grade school kid on a field trip to a slaughterhouse, pig farm, and chicken operation.

I saw a pig getting killed by a farmer when I was 5 years old; he brought my brother and I into a fenced-in area, opened the gate, the pig charged him (as I recall), and he shot it dead. Then he showed us how he ground up the meat into sausage.

This same farmer killed a rooster that had knocked down my brother (who was a toddler); I watched him skin it alive. His wife made "rooster and dressing" and gave it to us. I didn't eat any of it, because I didn't like onions.

Dang, now I'm hungry.

my neighbor's mother-in-law makes $61 every hour on the internet . She has been without work for nine months but last month her pay check was $21792 just working on the internet for a few hours. visit this site right here...............

????? http://www.cashbuzz80.com

my neighbor's mother-in-law makes $61 every hour on the internet . She has been without work for nine months but last month her pay check was $21792 just working on the internet for a few hours. visit this site right here...............

????? http://www.cashbuzz80.com

$89 an hour! Seriously I don't know why more people haven't tried this, I work two shifts, 2 hours in the day and 2 in the evening?And i get surly a chek of $1260......0 whats awesome is Im working from home so I get more time with my kids.

Here is what i did

?????? http://www.paygazette.com

Well,I just got a large package of Omaha steaks dropped off,in a truck,using gasoline.I will of course ,need to by fresh veggies to go with them,shipped from the south and or west,using fossil fuels.

Off narrative:

http://mobile.nytimes.com/2015.....-2010.html

I guess we better hope that the latest libertarian trope about how unprecedented climate change caused by rich 1st world countries that refuse to clean up their own mess won't be too bad. My fingers are crossed.

The rich countries are the cleanest and you know it's true.

Huffing? The United States is the 2nd largest emitter of co2 and one of the highest per capita.

Unlike others,I don't debate idiots,IO'm right,your wrong.

The United States is the 2nd largest emitter of co2

I thought we were talking about pollutants.

I knew you were out there

http://poorrichardsnews.com/po.....-on-record

You think an analysis of temperature data over 5 months in the United States gives you an idea of long term temperature changes worldwide? You are way behind the times anyway. Even heartland.org will acknowledge that it's getting hotter and, 30 years of denialism notwithstanding, that the reason is because of human industrial activity.

You should get with the times. Global warming is no big rip and changing the global temperature upwards by 4oF is going to mean that people that live in Boston will be able to go to Fenway in a light jacket in October--and nothing more. I hope they're right. Seriously.

Oh yeah, and it's going to cost one million percent of worldwide GDP to put up wind turbines even though hippies in Denmark and Norway are already doing that. Fuck that. I hate Gammeldansk.

So I assume you are a fan of climate change then?

How is it that you say solar and wind are going to be expensive (and it will be) in this post but a few posts down you chastise Suthenboy for praising cheap fossil fuels for giving him all of these great modern things?

Make up your mind and if you were trying to be sarcastic you completely and utterly failed (but that's OK cause it happens to the best of us).

american socialist:

You mean this Norway?

When you libertarian socialists whine about how psychotic the oil industry is, does that include private-public enterprises like Statoil?

It's so wonderful to see the advocates for social democracy and the nordic model steer clear of hypocrisy.

Wait, wait!? Are you saying that the dreamy socialist utopia of Norway is being floated by oil money? That it can't sustain itself?

I wonder what will happen when that goes tits up?

From the way socialists blame socialism on oil, I assume the answer is "Venezuela".

I wonder what will happen when Norway phases out oil and all those thousands of people will no longer be paying taxes to support the socialist paradise?

It probably takes a handful of people to run entire fields of wind mills and solar panels. A handful of people can't support an army all holding their hands out.

I thought all state run enterprises were doomed to failure. Do you think that socialists must blindly defend every government program or enterprise everywhere under the sun? I just don't want to disappoint but I am neither a fan of genocidal maniacs or-- down the line in importance-- corruption on the part of state-run enterprises.

I am sure that not all socialists do support everything the gov't does. However, there are many who do and will blindly follow their shepherds.

There is also a massive tendency on your lots part to try and ban anything and everything you don't like, which I think is really why the people who do, hate you (myself included).

Additionally, people fear regulation of their everyday lives. If we have social healthcare then people can start telling me what I can eat, if we have social energy consumption then people can tell me what temp I can set on my CC, etc.

I think what you guys fail to see is that there are people who favor freedom of the individual over safety, health, and whatever else the do-gooders want to do for my own benefit.

I understand that socialists are very discerning.

Still, considering that Norway's exports look like this, I would think that socialist democrats would either whine about the environment, or hold up the nordic model as the end-all, be-all of awesomeness, but not do both at the same time.

Otherwise, we can't be as awesome as Norway and really stick it to the oil companies, simultaneously. And, when you consider how many people in Norway work in the oil industry (since it's mostly owned by the government, do those count as public employees?), I'm not sure how environmentalism and the nordic model of socialism go hand in hand.

Wow, who woulda thunk it? A country's economy is based on the extraction and exploitation of natural resources.

I guess magical fairy dust and rainbows haven't really caught on yet.

" I would think that socialist democrats would either whine about the environment, or hold up the nordic model as the end-all, be-all of awesomeness, but not do both at the same time."

Norway generates more than a third of its energy from renewables. Why can't you be an environmentalist and a socialist again? I missed the logic... Not enough Murray Rothbard, I guess.

american socialist:

On a per-capita basis, it is the world's largest producer of oil and natural gas outside the Middle East.

Based on continued oil and gas exports, coupled with a healthy economy and substantial accumulated wealth, Norway is expected to continue as among the richest countries in the world in the foreseeable future.

Yes, this sounds like a country that's taking a brave, progressive stance on renewable energy, and against CO2. Bravo.

Also, who do you think those genocidal maniacs are? They sure haven't been just the everyday common joe have they?

Why is it if I defend capitalism and lesser regulation (not zero regulation) I get a history lesson about the robber barons and how wealth was concentrated in the hands of the few. But when I bring up that gov't is the greatest mass murderer and thief known to man, and absolutely prone to abuse its power, history doesn't matter anymore and I get told, "These things can't happen anymore."

But when I bring up that gov't is the greatest mass murderer and thief known to man, and absolutely prone to abuse its power, history doesn't matter anymore and I get told, "These things can't happen anymore."

It's not that they can't happen any more. It's just that comparing Nordic-style social democracies with Soviet communism is an apples-to-oranges comparison that right-wingers like to employ any time someone starts to talk about things like income inequality. It's bunk. Where exactly has the Welfare state failed?

Venezuela's welfare state isn't exactly rocking right now.

I know that you don't know me but I am no where near a right wing guy.

Well to be fair I am kinda traditional in my personal life but I would never dream of trying to force that on other people.

As Brian noted, Venezuela, and lets see, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, North Korea, Greece, Spain, USSR, and I'm pretty certain about a few more but not certain enough to post.

Socialism is just communism's younger brother. Not as big and overpowering but still cut from the same cloth.

Also before you say it, I consider Spain a failure because of massive unemployment (last I heard it was over 25% for young people)and other economic failures and Greece most certainly was a failure and wound have collapsed had it not been for the EU and particularly Germany. Hell even France isn't exactly rockin' it right now as they are facing near zero growth and high unemployment.

Can you please explain the difference between a libertarian socialist and a democrat? Other than some vague reference to questionable adherence to the NAP?

I don't know... There's lots of different types of libertarian socialists. You think Noam Chomsky is a Democrat? Ever hear him talk about Barack Obama.

amsoc:

Me, neither.

Now, go ahead and give people a good lecturing on how bad it is to carry water for the republicans.

Sucking democrat cock, though? Pure awesome.

You missed the point. The term libertarian socialist is too all-encompassing. It would include communitarianism and Marxism-- both of which have zero support in the Democratic party.

Can you tell me the difference between your brand of libertarianism and the views expressed by a dovish member of the Tea Party. I have trouble with that one.

amsoc:

I'm sorry: the term "libertarian" is too all-encompassing. I can't answer that question.

I can, however, go on shamelessly defending one popular political party, as if I love the taste of it's cock, while talking trash about the other popular political party. However, I'm really above popular, partisan politics, so much so that I have a special name for myself, similar to "libertarian socialist". Otherwise, though, I see how we're just different sides of the same coin.

You know, other than the part that I don't suck republican cock as hard as you suck democrat cock.

american socialist|1.16.15 @ 5:33PM|#

"You missed the point."

No, the point is simple:

You're a fucking liar and stupid besides.

And stupid rears it's ugly head again. Fuck off commie kid... your tenure her is fucking stupid.

Continue as it affirms your idiocy.

I can get in my jeep right now and drive down a very nice road to a very nice grocery store and buy food from all over the world. If my car crashes an emergency response team will show up within minutes and take me, within a few more minutes, to a fully staffed hospital. I have plenty of clean clothing and the easy ability to clean more. I have central climate control in my house. I have indoor plumbing. I have refrigeration for food storage. I have running water, electricity 24 hrs per day, and reliable transportation that gives me access to a continent. I don't have to worry about dysentery, smallpox, minor infections from small wounds, or dying from a tooth infection. Legions of parasites and pathogens that plagued my ancestors are held comfortably at bay.

Because one person can produce magnitudes more today than in the past in far less time I can spend my free time shooting skeet or building furniture purely for pleasure. I can take my grandson fishing not because we will starve if I don't, but for fun.

Do I need to go on? All of that and more are made possible by abundant, cheap energy. Nothing about the climate is deviating from the normal cycles of the past, and even that is easily shown to be driven by solar cycles.

That is what the environmentalists want to put a stop to. They want to rob us blind, prevent us from empowering ourselves. Not a single one of those evil, thieving fucks has any intention of casting themselves back into the stone age, only the hoi-polloi. The Goracle has made nearly a billion(?) dollars hyping his lies, all the while burning more fossil fuel than a thousand common people. His tripe is nothing more than a run-of-the-mill confidence game. The really slick and clever cons are probably laughing their asses off about how much he has managed to fleece with his simple film-flam.

I cannot for the life of me understand why anyone buys into this scam.

Because they've convinced them that the life the Indians lived was far better and more "in tune with nature". They leave out that we have more forests than 50 years ago, that there's more rain forest in Central America than when the Aztecs lived, and that GMO crops allow us to produce more while claiming less land. They ignore that all of the doomsday predictions have not come true and insist that Third World nations have no right to raise themselves out of poverty through energy.

All while playing on their smart phones, drinking water from plastic bottles, wearing modern clothes, driving, flying, watching TV, buying the latest gizmos, and ignoring that all of those things are *gasp* petroleum products.

They also ignore that every time the climate has changed, life has adjusted. Perhaps in a warmer climate we won't be able to produce as much broccoli or cabbage, but we can produce more corn and tomatoes. Maybe we will lose some land but we might gain a whole lot of fish. I don't know the answer to any of these things but I'm certainly not going to act like the world is ending just because it goes to a temp that we have had in the past and amazingly the world did not end.

It's amazing that a meteor can hit the earth or a super volcano can erupt and block out the sun for around a year and yet life still went right on its merry way but if the temp rises by 2C then we are all going to die a horrific death.

So you can't do all of the above if your house is powered by photovoltaics, if your plastics are formed from metabolic engineering, and your car and the ambulances that come to pick you up are powered by cellulosic ethanol?

I'm sure he can but those methods are not viable right now and are not as cheap as fossil fuels. We have tried and failed with wind and solar because they are not efficient enough yet.

Plant based ethanol is not quite the savior you want it be either. We are currently dealing with massive run offs of pollutants into the water sheds from farms where corn is raised for ethanol production.

The problem with these technologies is that they are relatively new and therefore expensive, prohibiting the common person. The oil barons are not these evil people who want to see the world burn, as they live here as well.

I'm sure given time all of the things you mentioned will become more common place. The thing that will irritate me is that the environmentalists will take the credit when it really will just be a natural cycle of the market making goods cheap and accessible as they become easier to produce.

You are a fucking moron. The subsidies for alternatives go to people that can buy a Tesla car or to the well to do that can get in on Musk's Solar City scam.

You fancy yourself a working class hero, you are possiblty the dumbest prog I've ever encountered.

The average person burned a lot more than 2,000 calories a day prior to the IR. One of the reasons the Bible Belt and African-American populations have an extraordinarily high obesity rate relative to the rest of the nation is that the traditional southern diet suited farmers and field workers who spent their days engaging in manual labor until the widespread use of tractors following WW2.

I'd imagine a pre-industrial peasant, French, Japanese, whatever, would burn at least twice as many calories as your modern American, which makes the development of resilient GMOs even more important for calorie-intensive developing nations that still rely on manual labor.

/nitpick

Net zero housing = energy INDEPENDENCE.

In other words, not dependent on the crony utilities or corporations.

just before I looked at the draft four $9879 , I didn't believe that...my... father in law had been truly erning money part time from there computar. . there dads buddy has done this for only 21 months and just repaid the dept on their apartment and bourt a great Land Rover Range Rover .

Read More Here ~~~~~~~~ http://www.jobs700.com

my neighbor's step-aunt makes $80 an hour on the internet . She has been laid off for five months but last month her payment was $12901 just working on the internet for a few hours.

website here........

???????? http://www.paygazette.com

just before I looked at the draft four $9879 , I didn't believe that...my... father in law had been truly erning money part time from there computar. . there dads buddy has done this for only 21 months and just repaid the dept on their apartment and bourt a great Land Rover Range Rover .

Read More Here ~~~~~~~~ http://www.jobs700.com

I'd like for Bailey to complement this review with an essay about how anti-fiat money ideologues use catastrophic hyperinflation prophecies to attack a central banking system they detest.

"Hansen and his colleagues published an open letter to "those influencing environmental policy but opposed to nuclear power." It forthrightly states: "Renewables like wind and solar and biomass will certainly play roles in a future energy economy, but those energy sources cannot scale up fast enough to deliver cheap and reliable power at the scale the global economy requires."

For radical environmentalists Hansen is a traitor for caring about the global economy. Part of the strategy to save the Earth from man is to get rid of man, so destroying economies around the world is actually part of the plan if you really pay attention and listen to many leaders of the environmental movement.

hguhf

friv 2

friv 4

friv3

hguf

al3ab banat

friv 1000

friv 3

Fight Poverty by Using Fossil Fuels