The 5 Best Drug Scares of 2014

A deluge of drunks, deadly synthetics, ecigs and smoking, heroin hype, and THC-tainted treats.

The history of drug control in America is a series of panic-propelled policies, most of which have not turned out very well. Those of us who support a calmer, more tolerant approach to psychoactive substances therefore spend much of our time defusing scares aimed at justifying or expanding the government's role in policing our bloodstreams. Here are some of my favorites from the past year.

5. A Deluge of Drunks

In January the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) noted with alarm that most Americans say they have never discussed alcohol consumption with a health professional. Physicians' reluctance to broach the subject is especially troubling, the CDC said, because "at least 38 million adults in the U.S. drink too much." Elsewhere the CDC says "29% of U.S. adults drink too much." Based on data from the National Health Interview Survey, that represents about 60 percent of Americans who drink as often as once a month.

How did excess become the norm among past-month drinkers? By bureaucratic fiat. According to the CDC, "problem drinkers" consist mainly of "binge drinkers," which does not mean what you might think: people who spend days in a drunken stupor, devoting themselves to intoxication in a way that seriously disrupts their lives. No, according to the CDC, a man is a binge drinker if at any point in the last month he has consumed five or more drinks "on an occasion"; for a woman, the cutoff is four drinks.

This definition is based on the amounts typically needed to reach a blood alcohol concentration of 0.08 percent, which corresponds to the legal per se standard for driving while intoxicated. What if you do not plan to drive? It does not matter. The CDC has decreed that no one should ever drink this much, no matter the circumstances.

Even if you never "binge," that does not necessarily mean the government approves of your drinking. The CDC also worries about men who have more than 14 drinks per week and women who have more than seven.

If you are a woman, don't think you can get a pass by sticking to one drink every day but Saturday, when you have two. That puts you over the government's limit and makes you part of the problem.

Unless you live in Canada, where 10 drinks a week are deemed OK for women; or the U.K., where women are safe if they do not "regularly" consume more than three "units" (1.5 glasses of wine) a day; or Italy, where they are allotted up to 40 grams of ethanol (nearly three shots of vodka) each day. Evidently the CDC's rules are not as obviously correct as it pretends.

The relationship between alcohol consumption and mortality follows a J-shaped curve, meaning that drinking more is associated with better health—up to a point. Where is that point? Around two drinks a day for women and four for men, according to a 2006 analysis of 34 prospective studies published in the Archives of Internal Medicine. That's a lot more generous than the CDC's quotas, and it is still probably a conservative estimate, since people tend to underreport their drinking, anticipating the sort of judgmental attitude that the CDC thinks is every doctor's duty.

Next: The real thing would be safer. 4. Turn On, Tune In, Drop Dead

According to the latest numbers from the Monitoring the Future Study, use of synthetic marijuana and synthetic cathinones (a.k.a. "bath salts") is declining among teenagers. The share of high school seniors reporting past-year use of the ersatz pot sold under names such as Spice and K2 fell from 11.4 percent in 2011 to 5.8 percent this year. Less than 1 percent of 12th-graders reported using "bath salts" this year, down from 1.3 percent in 2012.

The menace that the new synthetics pose to the youth of America nevertheless remains a popular journalistic theme, as reflected in stories about Cloud 9, a name that has been applied to stimulants as well as marijuana substitutes, and 25I-NBOMe, a psychedelic that popped up on the Internet a few years ago. The press coverage tends to exaggerate the dangers of such products. A Michigan police chief told a Detroit TV station, for instance, that Cloud 9 is "absolutely deadly," although another sourceconceded that "no deaths related to the use of Cloud 9" have been documented. And while 25I-NBOMe overdoses have been implicated in at least 11 deaths since 2012, that represents a very small percentage of the people who have tried the drug.

Still, the reporters and law enforcement officials warning parents about these drugs are right that untested, unfamiliar compounds may pose unknown hazards. The uncertainty that consumers face was highlighted by the fact that everyone quoted in the stories about Cloud 9 seemed to agree it was dangerous, but almost no one seemed to know what it was. Some sources claimed it was a marijuana substitute, while others identified it as a stimulant. According to at least one lab test, it was AB-PINACA, a synthetic cannabinoid first described in 2012. But it's not clear that's what everyone who bought Cloud 9 was getting.

The lack of reliable information, a perennial hazard of the black market, is especially worrisome when dealing with novel compounds that can be more dangerous than the drugs they are supposed to imitate. The unpleasant effectsattributed to the Cloud 9 sold in southeastern Michigan, for example, are quite different from what people expect when they smoke pot, which is not generally associated with "hallucinations, agitation and severe vomiting." And although deaths related to 25I-NBOMe seem to be pretty rare, they are more common than deaths related to LSD, which has been used by around 25 million Americans without being linked to any fatal overdoses.

By prohibiting one drug after another, thereby encouraging constant innovation by underground chemists trying to stay one step ahead of the law, the government encourages this sort of dangerous substitution. That point is generally lost in stories about the peril posed by the latest synthetic, which instead of prompting a reconsideration of the war on drugs encourage its escalation.

Next: No smoke, yet ire.

3. Is Aping Vaping Stoking Smoking?

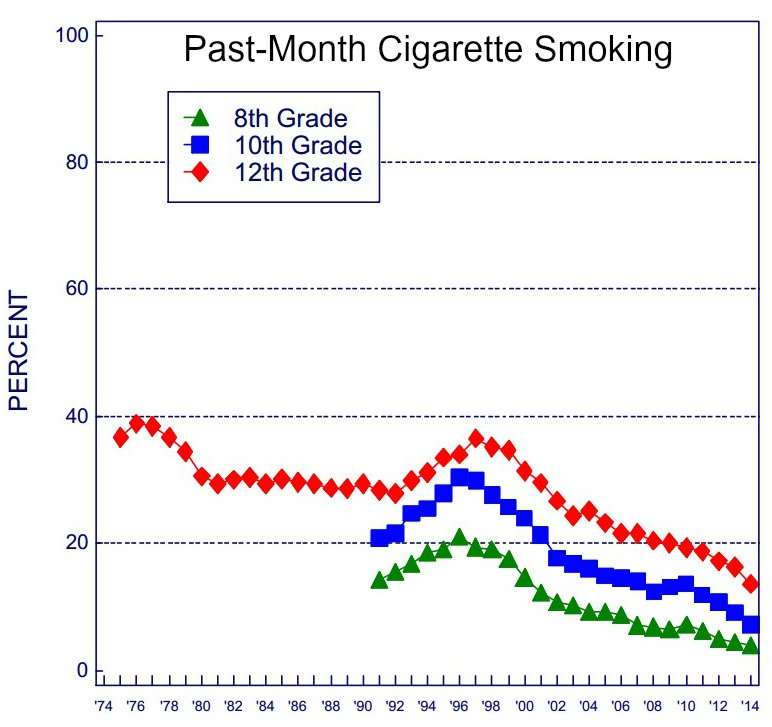

This year anti-smoking activists and public health officials continued to warn that electronic cigarettes are "reglamorizing" conventional cigarettes, encouraging teenagers to embark upon deadly tobacco habits. In an April interview with the Los Angeles Times, CDC Director Tom Frieden worried that e-cigarettes will "get another generation of kids more hooked on nicotine and more likely to smoke cigarettes." The following month, Tim McAfee, director of the CDC's Office on Smoking and Health,told a Senate committee the marketing of e-cigarettes is a "huge experiment" on "our children," who are unfairly being asked to "pay a potential price…for a hypothetical benefit to adult smokers." This month Stanton Glantz, a longtime anti-smoking activist, told USA Today "there's no question that e-cigarettes are a gateway to smoking."

Despite all these warnings, smoking by teenagers is less common than ever before, even as the popularity of vaping continues to rise. In the 2014 Monitoring the Future Study, 9 percent of eighth-graders, 16 percent of 10th-graders, and 17 percent of 12th-graders reported using e-cigarettes in the previous month. Those numbers are even higher than the rates seen in a 2013 CDC survey that Frieden considered alarming. Yet like the CDC survey, Monitoring the Future shows smoking rates are falling, hitting record lows in 2014.

A study reported this month in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine casts further doubt on the claim that "e-cigarettes are a gateway to smoking." In a 2013 survey of 1,304 college students, the researchers found that 43 had first consumed nicotine in the form of e-cigarettes, and only one of them was a current cigarette smoker. That smoker represented 0.08 percent of the entire sample, 1 percent of the current cigarette smokers, and 2 percent of those whose first nicotine product was an e-cigarette. The authors conclude that vaping "does not appear to lead to significant daily/non-daily use of cigarettes." Or as one of the authors put it last year, "It didn't seem as though [vaping] really proved to be a gateway to anything."

Next: It's not a real epidemic until it involves someone famous.

2. Hoffman and the Height of Heroin Hype

According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, which began in 2002, heroin use among Americans 12 and older peaked in 2006, fell sharply in 2007, rose in 2008, fell in 2009, rose through 2012, and dropped again in 2013. According to theMonitoring the Future Study, 0.6 percent of high school seniors used heroin in 2014, down from 1.5 percent in 2000. But judging from press coverage of the issue, we are in the midst of an escalating "heroin epidemic."

Mentions of that phrase in the newspaper and wire service articles collected by Nexis skyrocketed from 82 in 2011 to 273 in 2012 and 633 in 2013. This year there have been more than 3,000 references to a "heroin epidemic" in these news sources, reflecting the tremendous attention attracted by the actor Philip Seymour Hoffman's death on February 2 (which was caused by "mixed drug intoxication" but generally attributed to heroin alone).

That single incident generated more talk of a "heroin epidemic" than everything else that happened in the previous 12 years. Needless to say, the heroin-related death of a gifted and widely admired actor, though tragic, tells us nothing about the prevalence of heroin use or the direction in which it is headed. Judging from the survey data, coverage of the putative epidemic really took off around the time when heroin use started to fall.

Next: THC treat trick.1. Strangers With Cannabis Candy

When the Denver Police Department (DPD) warned parents to be on the lookout for marijuana-infused Halloween candy this year, it cited the recent opening of state-licensed stores selling such products to recreational customers. But marijuana edibles have been legally available to Colorado patients for years, so it's not like the sort of prank the cops envisioned was suddenly feasible, and it remained highly implausible: Why would someone waste expensive cannabis candy on trick-or-treaters, especially when he couldn't be sure anyone would actually eat it and he would not be around to witness the results in any case?

Although the opening of Colorado's pot stores provided a new hook, law enforcement officials have been issuing warnings about THC-tainted treats for years. They find a credulous audience in overanxious parents who are already carefully inspecting their children's Halloween hauls, looking for signs of razor blades, needles, and broken glass. All these stories feature seemingly friendly neighbors who want to hurt innocent children for no comprehensible reason, and they share another theme: a dearth of actual examples. "We don't have any cases of it," a DPD spokesman told me two weeks before Halloween. That was still true after the holiday had come and gone.

To some extent, this urban legend reflects the eagerness of pot prohibitionists to discredit legalization. But that motive does not explain the active participation of businesses that profit from legalization. CB Scientific took advantage of the scare to promote its THC test kits, which it markets to marijuana merchants and consumers. The Associated Press reported that the company "offered 1,000 free kits to parents wanting to screen their trick-or-treaters' haul for marijuana's psychoactive chemical," although it had only 45 takers. "Not that we believe anyone will be passing out pot candy to kids," CB Scientific co-owner Derek Lebahn explained on Facebook, "but if something does get mixed up or questioned, we do have a quick, accurate way of knowing."

A DPD video about the peril of THC-tainted treats featured Patrick Johnson, owner of Denver's Urban Dispensary, who may have been trying to boost his reputation as a responsible pot dealer but also seemed to share the widespread assumption that malevolent strangers are out to get your kids on Halloween. "If it looks like the package has been tampered with whatsoever," he suggests in the video, "you should use those same practices we've been using since I was a child, that it's best to dispose of that candy. I think the only ones who will be upset about that are the children's dentists." In other words, if you are already hypervigilant as a result of other baseless scare stories, what's one more phony threat?

This article originally appeared at Forbes.com.

Show Comments (23)