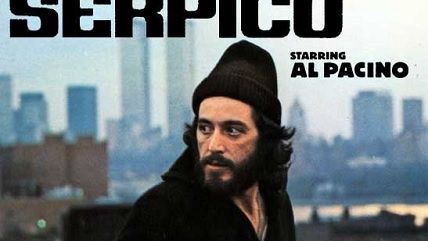

Frank Serpico Explains How Police Violence is the New Graft

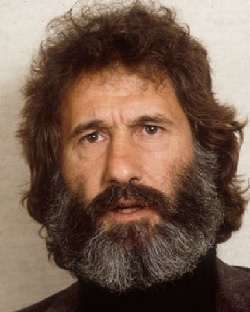

In 1971 Frank Serpico was shot in the face while opening a door during a drug bust in a Brooklyn apartment, and left there to die by the cops with him because Serpico had testified against crooked cops in the narcotics division. An elderly man in the building, not the other cops, called 911 to send an ambulance.

In a piece at Politico, Serpico explains that to this day he's shunned by the New York Police Department (NYPD). A Medal of Honor recipient, he's only been invited to the annual dinner once, when Bernard Kerik was commissioner. While the graft is, thanks to greater accountability, not as systematic as it used to be, Serpico writes, a lack of accountability is why police violence is such a problem. Via Politico:

I tried to be an honest cop in a force full of bribe-takers. But as I found out the hard way, police departments are useless at investigating themselves—and that's exactly the problem facing ordinary people across the country —including perhaps, Ferguson, Missouri, which has been a lightning rod for discontent even though the circumstances under which an African-American youth, Michael Brown, was shot remain unclear.

Today the combination of an excess of deadly force and near-total lack of accountability is more dangerous than ever: Most cops today can pull out their weapons and fire without fear that anything will happen to them, even if they shoot someone wrongfully. All a police officer has to say is that he believes his life was in danger, and he's typically absolved. What do you think that does to their psychology as they patrol the streets—this sense of invulnerability? The famous old saying still applies: Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. (And we still don't know how many of these incidents occur each year; even though Congress enacted the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act 20 years ago, requiring the Justice Department to produce an annual report on "the use of excessive force by law enforcement officers," the reports were never issued.)

It wasn't any surprise to me that, after Michael Brown was shot dead in Ferguson, officers instinctively lined up behind Darren Wilson, the cop who allegedly killed Brown. Officer Wilson may well have had cause to fire if Brown was attacking him, as some reports suggest, but it is also possible we will never know the full truth—whether, for example, it was really necessary for Wilson to shoot Brown at least six times, killing rather than just wounding him. As they always do, the police unions closed ranks also behind the officer in question. And the district attorney (who is often totally in bed with the police and needs their votes) and city power structure can almost always be counted on to stand behind the unions.

Serpico goes on to write that while he understands the need for cops to protect themselves, militarized gear isn't necessary in everyday situations—he says while he was off-duty he once disarmed a suspect who had three guns using just a snub-nose Smith & Wesson—and helped to isolate cops from the communities they're supposed to serve.

He also dismisses politicians who offer rhetoric but little action, all the way to the top:

As for Barack Obama and his attorney general, Eric Holder, they're giving speeches now, after Ferguson. But it's 20 years too late. It's the same old problem of political power talking, and it doesn't matter that both the president and his attorney general are African-American. Corruption is color blind. Money and power corrupt, and they are color blind too.

Read the whole thing, including Serpico's policy recommendations, here.

Show Comments (33)