It's the Presidency, Stupid

A conservative legal scholar's surprisingly convincing case against the Constitution.

The Once and Future King: The Rise of Crown Government in America, by F.H. Buckley, Encounter Books, 319 pages, $27.99

Good luck making sense out of what Americans tell pollsters. According to the Pew Research Center, fewer than one in five of us trusts the federal government. Gallup says that nearly three-quarters of us consider our leviathan "the biggest threat to the country in the future." Yet by equally overwhelming margins, Gallup shows Americans agreeing that "the United States has a unique character because of its history and Constitution that sets it apart from other nations as the greatest in the world."

Apparently, we're disgusted and frightened by our government as it actually operates. And yet we're convinced that we've got the best system ever devised by man.

On both counts, no voting bloc is more convinced than American conservatives. Few go quite as far toward constitutional idolatry as former House Majority Leader Tom Delay, who earlier this year proclaimed that God "wrote the Constitution." But the superiority of our national charter, with its separation of powers and independently elected national executive, is an article of faith among conservatives.

So it's about time for some constitutional impiety on the right. F.H. Buckley answers the call in his bracing and important new book, The Once and Future King. Buckley, a professor of law at George Mason University and a senior editor at The American Spectator, is unmistakably conservative. But that doesn't stop him from pointing out that America isn't so damned exceptional—or from arguing that the revered Constitution has made key contributions to our national decline.

In the conventional narrative, Buckley writes, "our thanks [must] go to the Framers, who gave the country a presidential system that secured the blessings of liberty." A "nice story," he says, but one that "lacks the added advantage of accuracy."

First off, we're hardly "the freest country in the world." As Buckley points out, his native Canada beats the United States handily on most cross-country comparisons of political and economic liberty. In the latest edition of the Cato Institute's Economic Freedom of the World rankings, for example, we're an unexceptional 17th. Meanwhile, as Buckley points out, the Economist Intelligence Unit's "Democracy Index" ranks us as the 19th healthiest democracy in the world, "behind a group of mostly parliamentary countries, and not very far ahead of the 'flawed democracies.'"

There's a lesson there. While "an American is apt to think that his Constitution uniquely protects liberty," the truth "is almost exactly the reverse." In a series of regressions using Freedom House's international rankings, Buckley finds that "presidentialism is significantly and strongly correlated with less political freedom."

In this, Buckley builds on the work of the late political scientist Juan Linz, who in a pioneering 1990 article, "The Perils of Presidentialism," argued that presidential systems encourage cults of personality, foster instability, and are especially bad for developing countries. Subsequent studies have bolstered Linz's insights, showing that presidential systems are more prone to corruption than parliamentary systems, more likely to suffer catastrophic breakdowns, and more likely to degenerate into autocracies. The Once and Future King puts it succinctly: "there are a good many more presidents-for-life than prime-ministers-for-life." Maybe what's exceptional about the United States is that for more than 200 years we've "remained free while yet presidential."

Relatively free, that is. The American presidency, with its vast regulatory and national security powers, is, Buckley argues, rapidly degenerating into the "elective monarchy" that George Mason warned about at the Philadelphia Convention. Despite their parliamentary systems, our cousins in the Anglosphere also suffer from creeping "Crown Government"-"political power has been centralized in the executive branch of government in America, Britain, and Canada, like a virus that attacks different people, with different constitutions, in different countries at the same time," he writes.

But we've got it worse, thanks in large part to a system that makes us particularly susceptible to one-man rule. As Buckley sees it, "presidentialism fosters the rise of Crown government" in several distinct ways. Among them: It encourages executive messianism by making the head of government the head of state; it insulates the head of government from legislative accountability; and it makes him far harder to remove. On each of these points, The Once and Future King makes a compelling-and compellingly readable-case.

"The character of the presidency is such," the British journalist Henry Fairlie wrote in 1967, "that the majority of the people can be persuaded to look to it for a kind of leadership which no politician, in my opinion, should be allowed, let alone invited, to give. 'If people want a sense of purpose,' [former British Prime Minister] Harold Macmillan once said to me, 'they should get it from their archbishops.'"

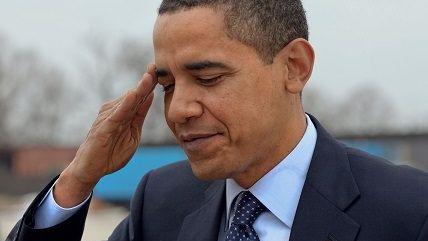

Presidential regimes invite executive dominance by combining the roles of "head of state" and "head of government" in one figure. "As heads of government," Buckley writes, "presidents are the most powerful officials in their countries. As heads of state, they are also their countries' ceremonial leaders," and claim "the loyalty and respect of all patriots." Where parliamentary systems cleave off power from ceremony, presidential ones make the chief executive the living symbol of nationhood: the focal point of national hopes, dreams, fears, and occasionally fantasies. In February 2009, author Judith Warner took to her New York Times blog to confess that "the other night I dreamt of Barack Obama. He was taking a shower right when I needed to get into the bathroom to shave my legs." Warner's email inquiries revealed that "many women—not too surprisingly—were dreaming about sex with the president."

Buckley notes that "Britons tend not to chat with David Cameron in their dreams," which presumably rules out soapy frolicking as well. Nor do Brits tend to look to the prime minister for a sense of national purpose or as a cure for spiritual "malaise." Prime ministers are "more likely to be figures of fun…or the butt of slanging matches during Question Period in the House of Commons." Indeed, the parliamentary practice of Prime Minister's Questions, in which the chief executive is regularly and ruthlessly grilled by the opposition, goes a long way toward explaining why there's no such thing as the Cult of the Prime Minister.

Presidents can isolate themselves in a cocoon of sycophants, even putting protesters in "Free-Speech Zones," where their signs can't offend the liege. And the exaggerated ceremony of the office "tends to make criticism of a president seem like lese-majeste," as Justice Samuel Alito learned when he dared mouth the words "not true" while Obama was pummeling the Supreme Court in his 2010 State of the Union address.

"Thin-skinned and grandiose" characters do better in presidential regimes, Buckley writes, whereas "delusions of Gaullist grandeur are fatal for Prime Ministers." In the U.K., they have to face the music in person each week. The aforementioned Harold Macmillan admitted that the very prospect used to make him physically sick.

The prime minister's Question Time is but one facet of the superior executive accountability offered by parliamentary systems, Buckley argues. Such systems, he maintains, also do a better job of restraining executives' proclivity for launching wars.

It's a counterintuitive claim. In the U.K., warmaking is a royal prerogative exercised by the prime minster, and parliamentary approval is optional. In the U.S., Congress has the power to declare war and the power of the purse, which Jefferson looked to as an "effectual check to the Dog of war."

That's the theory, anyway. In practice, Buckley shows, "the absence of the separation of powers in parliamentary regimes and the government's day-to-day accountability before the House of Commons make it far more difficult for a prime minister to disregard Parliament's wishes." Meanwhile, U.S. congressmen reliably punt on questions of war and peace and hardly ever object to funding wars they never approved.

Buckley over-eggs the pudding a bit when he writes that "if one really wants a militaristic government and imperialism, presidential regimes are the way to go." The British Empire managed well enough, having at one time or another made war on all but 22 countries around the world.

Even so, our countries' respective debates over whether to bomb Syria made for an instructive contrast. Last September, Secretary of State John Kerry kept insisting that "the president has the power" to wage war "no matter what Congress does." When the House of Commons rejected airstrikes, Kerry's counterpart across the pond simply said, "Parliament has spoken."

Finally, parliamentary systems do better on the ultimate question of accountability: They make it easier to "throw the bum out" if all else fails. "Prime ministers may be turfed out at any time by a majority in the House of Commons"; they can also be replaced by their party without bringing down the government. Presidents serve for fixed terms, and since we've never, in 225 years, successfully used the impeachment process to remove one, anyone who's not demonstrably crazy or catatonic gets to ride out his term. We're stuck with the guy, thanks to our peculiar system of separated powers.

That system isn't all it's cracked up to be. It's not even what the Framers wanted, Buckley argues. Madison's Virginia Plan featured an executive chosen by the legislature. The Framers repeatedly rejected the idea of a president elected by the people—that option failed in four separate votes in Philadelphia.

What they envisioned was something much closer to parliamentarianism. As the Convention drew to a close, most of the Framers thought they'd settled on a system where presidential selection would usually be thrown to the House, since, after Washington, they didn't expect "national candidates with countrywide support would emerge." It was only after the Convention that Madison became the "principal apologist" for the emerging system of strong separation of powers.

Buckley is relentless in cataloging that system's defects. It's made the executive the most dangerous branch, he writes, fostering one-man rule when "deadlocks produced by divided government…encourage a power-seeking president to disregard the legislature and rule by decree."

Still, is there anything that separationism is good for? It stands to reason that the lack of separated powers in parliamentary regimes makes it easier to get big, bad things done.

Buckley acknowledges the point, but counters that it's also easier to get them undone, and that with a fiscal apocalypse looming, reversibility is more important. That's a plausible thesis, but I'd have liked to see more actual evidence on how well parliamentary regimes do at repealing bad laws and programs.

Buckley also spends comparatively little time on the relationship between regime choice and size of government. He notes that in the 1990s, presidential regimes had lower per-capita spending than parliamentary ones, but "since then, the gap has narrowed considerably—and this is before the bill for Obamacare comes due." But the U.S. still spends less on average than other wealthy democracies, including most first-world parliamentary regimes. And as far as "the bill for Obamacare" goes: Without the separation of powers, there's little doubt the U.S. would have had nationalized health care long before 2009. As Yale's Theodore Marmor, a leading scholar on the politics of the welfare state, argued in Social Science & Medicine in 2011, if the U.S. "had a Westminster-style parliamentary system, it is likely that America would have adopted national health insurance over 60 years ago when President Harry Truman proposed it."

Some scholars have found that presidential systems' apparent advantage on government expenditures vanishes under close scrutiny. But even if the tradeoff is higher government spending in exchange for somewhat greater freedom and a more restrained and accountable chief executive, it's not a trade we have the power to make. "All of this is irreversible," Buckley warns the reader in the book's very first chapter. In the last chapter, he notes that it's "a bit late in the day to adopt the parliamentary form of government the Framers had wanted" before half-heartedly outlining a few reforms he admits won't solve the fundamental problem.

Nobody likes hearing that sort of thing. But personally, I value an accurate diagnosis even if it doesn't come with a magic cure-all. Buckley's Once and Future King makes a powerful case that we're even worse off than we thought.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

That sounds right. Say what you like about Australian politics, Obama wouldn't survive a week here. But I think Americans collude in this - addressing former Presidents as Mr President, building Presidential libraries etc etc. To an outsider, you appear weirdly respectful. Or am I wrong?

Presidential libraries are pointless and should be taxed into poverty.

Ex-Presidents don't deserve to be called more than 'hey you' unless you actually know them personally.

"Ex-Presidents don't deserve to be called more than 'hey you' unless you actually know them personally."

And in that case, you probably wouldn't be as courteous.

I've accidentally driven right past a presidential library, without the slightest urge to go inside and see a monument to a sociopath who clawed his way to the top.

The Constitution wasn't meant to protect liberties, it was meant to take away liberties that existed under the Articles of Confederation.

To an outsider, you appear weirdly respectful. Or am I wrong?

Libertarians respect no one and rightfully so. Wrong in that sense.

But try positing that on Raw Story or a Breitbart with a Bush in power and the tidal waves of ejaculatory awe will literally drown you. Right in this sense.

I think he meant America is a nation. I agree with him.

It's not just presidents.

Our media has created a form of nobility by referring to all retired officeholders by the title of the office.

It's pretty disgusting, actually.

I've come to the conclusion that we really miss royalty. So we have to kind of invent it.

It's not technically correct to refer to more than one person as Mr. President. But he is literally the most powerful person in the world (inasmuch as his office affords him the capability of destroying the human species), so it sounds weird to some to call an ex-president "Mr. Clinton."

I think it's strange to address former presidents as "Mr President". Only one person holds the office at a given time. It's a custom I'd be happy to see fall by the wayside.

The last time I paid more than $10 for a book was... The Complete Far Side. I don't do social signalling, so there's no point in bying hardcover. Do you have a $3-4 eBook version?

A largely ignored problem about e-books is that, if only e-books, they are just that which they are ... e-books. They exist only in the ether of cyberspace. Accordingly, their content can be changed by anyone who controls the server on which they are housed or deleted entirely at the press of a button. For a movie, albeit not without its faults, see the first version of "Rollerball" with James Caan.

Except I've got ebooks stored offline. Multiply that by thousands of users and its a non-issue. And if word ever got out about a publishing house messing around with content, it could go quite badly for them.

I agree that we've put too much power in the executive, but parliamentary systems have fewer checks and limits on their power. Not to mention that the executive power in the U.S. has grown largely because the legislative branch has, time and time again, refused to use any of the powers granted to it under the Constitution.

The answer isn't fewer checks on power; the answer is more.

agreed. However, those checks are useless if the three branches decide to ignore them. The case of Wickard v Filburn being a prime example.

The executive stacked the court, the court issued a finding that flies in the face of the constitution and the legislature went hog-wild creating regulatory agencies who by proxy created an ocean of crushing regulation that has the power of law. All of it despite the checks, balances, and constitutional boundaries.

I think we have the best system ever devised...on paper. Without the proper character in the american people no system will work.

However, those checks are useless if the three branches decide to ignore them.

That more or less sums up the problem. Whatever system you have you are always going to run into the watchman problem.

I concur. I don't see the problem here as the fault of the Constitution, but rather the industry of those bent on circumventing its checks and balances. We're at a point where the advantages of eliminating the Presidency entirely might seem to outweigh the disadvantages, but we got here only after decade after decade of erosion of limitations of power.

The problems with the checks and balances of our system of government is that they create a large amount of systemic inertia, with the system only responding to consistent long term pressure.

And the problem with that is that real small government reform efforts are always intense but short lived. People that want less government involvement have businesses to run, families to raise, hobbies to pursue, in short lives to live. And therefor cannot and will not dedicate decades of effort their cause.

As opposed to people who want to grow government and organize their entire lives around that effort.

We would have had real reform at several times in my life, most recently 2010, in a more open government system with less inertia.

All good points.

Add in a mix of ignorant, short-sighted, easily manipulated, and/or partisan citizenry, mixed with a largely partisan media-academic complex, and any chance at retarding power-creep is continually nullified.

-- However those checks are useless if the three branches decide to ignore them.

I think that ignoring them is largely related to the position of Our Dear Leader. Congress would be more likely to use impeachment and SCOTUS would be more likely to strike down something like Obamacare if this wasn't going to be seen as an attack on His Holiness, The President. Because an attack on the President is an attack on America!

By separating our national-leader/head-of-state/face-of-the-country from the Executive Branch of the federal government, it becomes easier to actually apply checks and balances without giving a black eye to the country.

Why's it gotta be a black eye??

"black eye" in the popular view. The average American citizen sees impeachment or SCOTUS rebuke of a President's signature law as a huge embarrassment and shame.

In short, they don't want to discipline their child in public because they're afraid it'll make them look like a bad parent. So, the kid just asks worse.

IMHO, no, it's not a black eye. It's a proud moment that deserves a gold star and a trophy because we're standing behind the values that we (claim to) hold as the basis of our country.

The symptom which is the imperial presidency is only that, a symptom of the larger more destructive effect of the concentration of power in government, in general. Do you really think that Congress, the bureaucracy, or the Courts solve problems any better or are less susceptable to error or corruption.

The constitution's most important tenet is that power should devolve to the individual, that government has no power except that which is given it by the people. The reason the presidency should have less power is that the federal government should have less power.

, time and time again, refused to use any of the powers granted to it under the Constitution.

They've done everything they could to offload it.

The regulatory agency, a concept which I've come to loathe over the years is probably the shining example of that.

We could do a lot for this country if we'd change how regulatory agencies operate, with some very simple, straightforward changes.

The problem with a president is that it makes it easier to get shite done. Almost ideally, you'd have a system of government where the arseholes who are attracted to power would sit in a room squabbling about stuff they want to do, but be so circumscribed by their inability to levy taxes and inability to opt into an entirely voluntary governance that nothing but committee reports and toothless resolutions would ever get "accomplished".

Ideally, that seat of government would be a privately-run insane asylum.

Should read "inability to force people to opt into an entirely voluntary governance"

That's why we need a Bureau of Sabotage.

I really don't see what would keep such a system from eroding the limits on their power to levy taxes and opt into mutually avaricious "governance". The Presidency has merely been the shortest path to corrupt power. I'm confident that other paths would have been found in its absence.

I think our system would definitely be improved if the prez had a similar question period in congress

The author makes much hay about how the Brits laff at our elevating the president etc. vs how they dont with their PM but let's not forget that they have an entire monarchy to invest the reverence towards

We may have some silly foibles about our president but it's not one hundredth as silly as having official royalty

It does mean we invest the reverence in someone who has no political power whatsoever, which strikes me as a bit healthier. They're a sort of institutional celebrity

It does mean we invest the reverence in someone who has no political power whatsoever

A relatively recent historical development. Bear in mind that the American presidency was conceived of in 1787, and your Queen Elizabeth bears about as much resemblance to then-King George III as our President Obama does to then-President George Washington.

That's the point: they invest their reverence in a monarch with no power, and ridicule the PM who actually has it.

Why that's a bad idea I'm sure I don't know.

A king in government ideally works the same as a king in chess: he doesn't do anything, he just prevents anyone else from occupying the space.

Presidents can isolate themselves in a cocoon of sycophants,

an exultation of larks, or a skulk of foxes.

Is that really the right collective noun for sycophants? What about a lick of sycophants?

I think cocoon works well. Describes what being surrounded by a bunch of them does.

Perhaps you're thinking of "a lick of sense".

*cents*

*** gets coffee ***

There are two:

"Press Corps"

and

"Voting Block"

I like a murder of sycophants better. Has a nice ring to it.

"But that doesn't stop him from pointing out that America isn't so damned exceptional?or from arguing that the revered Constitution has made key contributions to our national decline."

It isn't the structure of the Constititon that is the problem but the failure of all three branches of government to abide by it as it is written.

As James Madison said, "The powers delegated by the proposed Constitution to the Federal Government, are few and defined."

It is the failure to adhere to those constraints - not the existence of an executive branch that is the root cause of the decline. The other 2 branches of government have likewise engaged in grabbing power that is nowhere authorized in the Constitution.

Checks and balances are so quaint.

Indeed. Even *Britain* is getting rid of checks.

Meaning there are only two possible ways to view the constitution: either it authorizes our form of government, which makes it a monstrosity, or it failed to prevent it, which makes it a failure. Not much to celebrate either way.

In the end, it's a piece of paper that merely said, "Here are the rules".

As a people, we can collectively say, "Fuck the rules, we just wanna get loaded and party".

The Constitution, not being a human entity, cannot prevent anything. We either pay attention to it, or ignore it.

Ultimately, we either punish those who ignore it, or reward them.

We've chosen the latter. It is us who failed the Constitution.

The explanation for the apparently disconnected poll results is really pretty simple.

The first set of results - the distrust of and perception of threat posed by the US government - is an assessment of the facts experienced by Americans in their own lives.

The second set of results - ""the United States has a unique character ..." - is just a regurgitation of the propaganda they learned in 9th grade, which is when most stopped learning history.

Lots of people criticize the public schools, but it seems to me that they are doing a great job in their primary mission: indoctrination.

I didn't need to go to no fancy HIGH SKOOL to know 'Murka is AWESOME.

I told that Kindergarten teacher the only letters I needed to learn was U, S, and A!!

It could also have something to do with the divergence of our modern government from the practical and philosophical basis of its conception. Kind of a "Do you like the NFL?" vs "Do you like football (handegg)?" type of thing.

Question period? How dare you question the president!

Hoit it up JD, hit it up.

http://www.Ano-Web.tk

Buckley doesn't go far enough.

Separation of powers itself, including an independent judiciary, were a mistake.

Flawed, Indeed

"An autopsy of history would show that all great nations commit suicide." -Arnold Toynbee (1889-1975)

Assuming both the value of democratic republics and of their individual citizens, Mr. Buckley characterizes the U.S. Constitution correctly ... flawed, indeed. Such is not to say, nevertheless, that the document is not without its merits; triumphant merits, at that. Even so, it was criticized rightly for some of its flaws by the anti-Federalists in 1787. Those flaws reflected two, fundamental issues; one political, the other scientific ... both beyond the control of the Federalists.

The political issue, of course, was slavery; without the North yielding to the South, there never would have been a Constitution in 1787. The scientific issue was the primitive state of Science and the non-existence of the Scientific Method; the guidelines of the latter being specificity, objectivity, and accountability.

Slavery, based upon race, no longer is an issue although slavery of the productive to the unproductive has become one. Science ... biobehavioral science, in particular ... now exists and is available although neglected passively if not rejected actively. In fact, biobehavioral science is the remedy ... and the only remedy ... to the flaws addressed by Mr. Buckley (www.inescapableconsequences.com).

The state has replaced morally indefensible slavery with legitimized public slavery. The Civil War inadvertently ended one type of slavery within this jurisdiction and quite advertently established a much more lucrative universal partial slavery. Chains are more effective when you don't see them.

"The Civil War inadvertently ended one type of slavery..."

I'd submit a minor correction to this (IMHO) otherwise insightful observation.

The "Civil" War didn't end anything, per se. THOSE WHO PROVOKED and PURSUED the "Civil" War, and exploited the chaos of its aftermath to implement the "American System" of economics put an end to black African slavery in the remainder of the States, and instituted a new form of slavery across the entirety of the U.S. population through crony capitalist wealth redistribution, federal income tax, inflatable fiat currency and, eventually, the welfare state entitlement system.

In short: the war, itself, did not do this. Those who provoked the war, and waged it against American civilians, along with their successors in the resulting oligarchy, were responsible. This is the true legacy of The Party of Lincoln: the Leviathan Lincolnite State.

Behavioral science is what sociopathic dictators use to manipulate the masses. It's not a "remedy". The remedy is for the people to get educated.

And, no, the sky isn't falling. The US is doing very well compared to other countries anyway.

Buckley is pursuing misdirection. His argument asserts that the Constitution specifies a "presidential system" and is therefore flawed. He ignores the root cause of the problems we face: that the limitations imposed by the Constitution are systematically IGNORED by our Leviathan Lincolnite federal State.

This has led to the ascendancy of the very oligarchy Jefferson predicted when he warned about the dangers of a federal government allowed to usurp sole authority over the limits of the federal government's authority.

If Obama and his predecessors have behaved like kings, you can thank Hamilton. Beginning in 1860, the implementation of his ideals completely subverted the Republican Form of Government guaranteed by the Constitution and, with that, destroyed the balance that guarantee was intended to preserve. The larger problem Buckley ignores is this subversion: the FUNDAMENTAL TRANSFORMATION of the Republic into a de facto empire ruled by D.C. using the threat of military force. Clearly, this is because it destroys his sensationalist assertions.

No. It's not (just) the Presidency. It's the 14th & 17th Amendments; it's "judicial review" & "incorporation doctrine", it's federal income tax, central banking, fiat currency, "internal improvements" pork, regionally unbalanced protectionist tariffs and all the rest of "American System" economics which, by design, concentrate all civil authority and political/economic power into as few hands as possible.

http://bit.ly/1p6qQml

But this subversion would not be possible without a passive, acquiescent public allowing those in power to continually seize more of it.

And a democratically elected 'king' is by far worse than a hereditary one. Where a hereditary king might regard the state and it's territory to be his property, a publicly elected king is merely a temporary caretaker. Thus a propertarian king has incentive to preserve the capital value of his 'property' while a public caretaker has incentive to loot as quickly as possible, before others do so.

Moreover with a hereditary king you stand a fighting chance of having a decent or at least non-evil person occupying that position, but with a democratic caretaker the person is almost guaranteed to be a demagogic sociopath, as the democratic system selects for those who are basically the best at lying, pandering and looting.

"The god that failed"

Smart man.

Perhaps the American Revolution was, as one author has put it, "A Great Mistake".

Or rather, I think you're referring to the conclusion at which one arrives after reading any of your comments, ever.

Sometimes I think I am batman.

As written, the federal government, and hence the president, simply shouldn't be responsible for much under the Constitution; the US was supposed to be an area of common defense, free trade, and free movement. The enormous expansion of federal powers isn't the fault of the Constitution, it tries to state as clearly as possible that that shouldn't have happened.

The Constitution only attempted to guarantee liberty at the federal level; states still could impose fairly significant restrictions of it, but freedom of movement, something the federal government should guarantee, would have made that self-limiting.

The fact that Canada scores better on the Index of Economic Freedom isn't a sign of a principled respect for liberty in that country, it's a sign of rational decision making in government. Note that #1 and #2 on that list, Hong Kong and Singapore, are very far from states offering their citizens liberty.

On the other hand, it is true that the US's lower score is a sign of a certain lack of liberty, namely the fact that economic and social populism can override economic liberties: that a majority can vote to take away property rights from a minority, and has done this with increasing frequency. But that's a problem the authors of the Constitution were aware of and tried to address; the fact that their warnings and efforts have been ignored isn't the fault of the Constitution.

I don't often quote those from the Chicago school except Milton Freidman

"You can have capitalism without freedom, but you can't have freedom without capitalism."

One is the prerequisite to the other.

Yes, capitalism is necessary for freedom, but it is not sufficient. All the countries ahead of the US in the Heritage Ranking may be more capitalist than the US, but they are not necessarily more free. That makes the Heritage Ranking worthless as an indicator of freedom.

The Economist Democracy Index is even more worthless, placing numerous unfounded values judgments on numerical indexes. For example, it gives a higher score to nations with high voter participation rates and less diverse opinions; numerous questions hinge on complex semantic questions. I can tell you for several countries, the score that the Economist has given those countries is absolutely not justified.

The Heritage Ranking has some value for policy ("why are corporations leaving"). The Economist Index is worthless political propaganda masquerading as science.

It's really quite simple. The government we have now isn't following the simple rules laid out in the constitution. 200 years of precedent law have consistently eroded the original intent of that document until what we have left is almost unrecognizable.

Just as a single example what about the 4th amendment? Are the American people really safe from unreasonable search and seizure or is walking into an airport probable cause that you have or are about to commit a violent crime and therefore subject to a search based on your criminal desire to fly somewhere in a timely manner?

I think that's a bad example, because providing airports and air travel really isn't a proper function of government to begin with.

In a more libertarian world, the airport and the airlines would be completely private and responsible for their own security (they would also be liable to the tune of about $10M/passenger for any passenger lost). They might choose not to engage in intrusive searches as a matter of good customer service, but they could certainly make whatever intrusive searches they want to perform a condition of transporting you.

Except they couldn't profile! Because that would not just make sense -- it would be, you know, racist or something.

In a more libertarian world, we'd have private airlines doing searches, and Occupy Airpot holding signs saying, "Koch Bro$ Want to Make Sure Your Pocket$ are 3mpty in their $ky!!1!"

The constitution does protect liberty, it's just that both R's and D's prefer power and security to liberty. The greatest fear of the average American is a fellow American with rights.

The problem isn't the Constitution; it's that we've intentionally eviscerated the structure it originally provided. The reason the President is selected by the Electoral College is that he was supposed to be selected by the states, who designated the delegates. This was designed to keep presidential elections from becoming personality contests. And the 17th Amendment destroyed the fundamental bicameral structure of Congress, turning the Senate from a body representing the interests of the states as semi-sovereign entities into a glorified House of Representatives elected directly by the people. Elimination of those two colossal mistakes would go far in repairing the flaws in our current government.

I too have been leaning towards parliamentary systems being superior .

One amendment I am thankful for is the 22nd after experiencing America's President for Life FDR . Interestingly Eisenhower who was the first affected didn't like it .

I think it would help a lot if the President were subjected to weekly accountings to Congress .

The constitution maybe flawed, but if one reads the Debate on the Constitution, and reads what many of the Federalists wanted, you'd see it was pretty damned useful. And, after all, Jefferson said revolution was necessary about every 75 years or so. He knew that as good a document as it was, government would get twisted around and need clearing out. We're a couple of revolutions behind...

http://www.amazon.com/The-Deba.....094045081X

The Presidency would be fine without the Seventeenth Amendment and the Administrative Procedures Act.

"... without the Seventeenth Amendment and the Administrative Procedures Act...."

And "incorporation doctrine" and "judicial review" and the 14th Amendment and the Hamiltonian wealth redistribution system set up to facilitate crony capitalism, federal income tax, fiat currency, a central bank / centrally-controlled economy... and all the other facets of "American System" economics that concentrate virtually all authority and power into a few hands in D.C.

It's not that the President is ignoring the "will" of Congress. The entire federal government - all three branches, combined - has not only usurped civil authority well beyond that delegated to it by the Constitution, but seized virtually all political / economic power over the entirety of the U.S. citizenry as well; States be damned.

That the President then behaves like a king in this context should not surprise anyone.

Why would you want to get rid of judicial review?

Switzerland did it right. Based their Constitution on ours. Saw the danger of a powerful President.

So they created a committee form of Presidency - based on Pennsylvania's 1776 Constitution. In their case, seven people form their Federal Council - each with four-year terms (no limits) - each responsible for different cabinet/departments - and the Presidency rotates each year to one of them.

They are elected by the combined legislature rather than direct vote - but other than that it is near perfect. It adds a new level of checks/balances (execs competing among themselves). The rotation reduces presidential preening. If directly elected, voters themselves could force more competition or more cooperation.

The only real danger would be a 'Caesar crossing the Rubicon' with whoever is in charge of the military - but that is always a danger.

And the power of that system was proven in WW2. The Nazis didn't consider Switzerland a legitimate country (a pimple on the face of Europe and a misbegotten branch of the Volk) and planned invasions twice. But with a militia that simply fades away, there is no military to force a surrender on. And the Swiss President at the time said 'Even if I am forced to surrender, no one knows who I am.' It's like trying to wrestle with jello that shoots back. so the Nazis moved on to more conventional enemies against whom they could 'win'.