The ISIS Conspiracies

How a century's worth of anxieties about America's southern border are affecting the latest foreign-policy crisis.

The first ingredient was a sudden influx of immigrants over the southern border. The second was a war on the other side of the world, putting Americans on the alert for foreign plots. Just to make people more nervous, there was violent chaos in Mexico that the authorities clearly couldn't control. Add those together, and nervous Anglos were bound to start seeing the Rio Grande as another front in the war. The border itself seemed to be a threat—the sort of hazard Texas Gov. Rick Perry had in mind when he worried that there's a "very real possibility" that "individuals from ISIS or other terrorist states" are entering America from Mexico.

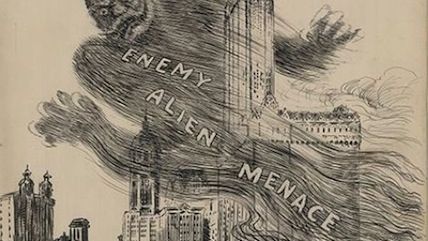

But Perry wasn't born yet. This period of border fear erupted a century ago, when the violent chaos to the south was the Mexican Revolution, not the drug war, and when the fighting on the other side of the Atlantic was World War I, not a Middle Eastern free-for-all. Throughout the 1910s, Anglo-Americans fretted about Mexican conspiracies to raid border towns, to set off domestic insurrections, and, after the European war broke out, to collaborate with the Germans.

Those notions weren't completely groundless. Border raids did periodically happen, most infamously when around 500 guerillas led by Pancho Vila attacked the town of Columbus, New Mexico, in 1916. The Plan de San Diego, a scheme to launch a revolution in the American southwest, really did exist, though when the uprising came it didn't amount to much. (Far more people were killed in the anti-Mexican pogroms that followed.) And in the infamous Zimmermann Telegram, Germany's foreign minister did offer to help the Mexicans recover their "lost territory in New Mexico, Texas, and Arizona" if they would join the war on the German side. (The proposal, which Mexico did not accept, helped push the United States into World War I.)

Facts like these fueled far more dubious tales, which in turn sparked surveillance and repression of Mexican Americans who had nothing to do with any espionage or violence. In East Los Angeles: History of a Barrio, Ricardo Romo calls this anti-Chicano crusade the Brown Scare. (This is unrelated to America's periodic panics over the far right, which have also been described as Brown Scares.) In an especially bizarre episode in 1917, the sheriff of Los Angeles County realized with alarm that thousands of Mexicans had suddenly quit their jobs and left the city; he speculated that "trouble" was on the way. The trouble never presented itself, but a more likely explanation for the exodus did: Employers elsewhere were paying higher wages.

It would not be the last time anxieties about the border would be overlaid with fears of some subversive force. In 1940, for example, the sheriff of El Paso County became convinced that local labor leaders were controlled by the Communists—he basically believed that everyone in the CIO was controlled by Communists—and that these reds in turn were linked to organizers in Juárez, Mexico. The House Committee on Un-American Activities came to investigate, and the county attorney was soon warning that "aliens" were coming "to plow the ground for the planting of the Soviet seed."

More recently, parts of the American right have combined their fears of Mexico and Muslims, worrying that a Middle Eastern enemy would strike the U.S. from the south. In the wake of 9/11, texts like Michelle Malkin's Invasion argued that lax controls along the border (and elsewhere) were paving the way for another attack. In 2011, Gov. Perry claimed that "Hamas and Hezbollah are working in Mexico…with their ploy to come into the United States." And now we have ISIS, a group whose very name, with its scent of ancient mystery cults, seems tailor made for conspiracy stories.

The ISIS stories aren't very plausible. ISIS has focused its energy on seizing territory and building a state, not establishing cells to carry out attacks around the world. The leaders who went to war with ISIS, including the president himself, have conceded repeatedly that they have no evidence the group is plotting against America, stressing instead the possibility that it will be in a position to attack us in the future. And if an assault is brewing, the Department of Homeland Security doesn't think it involves Mexico. Last week several senior officials from the department told Congress that they don't, in one speaker's words, "have any credible information" involving "known or suspected terrorists coming across the border." The most the agency had seen was some "social media exchanges" in which ISIS supporters discuss a cross-border attack as "a possibility." In other words, some people kicked the idea around on Twitter.

Are the White House and Homeland Security capable of getting their facts wrong? Absolutely, though right now their incentive is to err on the side of fear, not calm. Have people with some sort of terror ties entered the U.S. via Mexico in the past? Yes, though that doesn't seem to be the most common route. Is it possible that ISIS might shift some resources toward trying to kill Americans in America instead of the Middle East? Sure—particularly now that Washington is at war with the group. (There's a good chance the Pentagon's air strikes are making us less secure, not more.) But if you want to convince me that ISIS cabals are lurking beneath Texas and preparing to charge, you need to present some convincing evidence. Instead we get rumors and conjecture.

The most widely cited ISIS-invasion tale appeared when the conservative watchdog Judicial Watch announced that "government sources" believed ISIS was planning attacks from a base in Juárez. The sourcing was vague, officials denied the report, and no one has managed to corroborate it. And that weak yarn is the story with the strongest evidence. Go beyond that and you find folks like Gary Painter, the sheriff of Midland County, Texas, whose reason for believing an ISIS plot might be afoot is that illegal aliens have allegedly left "Muslim clothes" and "Quran books" along their trail. Or the Breitbart article announcing that a "Muslim prayer rug" had been discovered on the Arizona border. (On closer examination, the item appears to be an Adidas shirt.)

The real source of this anxiety amounts to a hunch, not a clue: a general unease about people crossing frontiers. Movement and privacy are essential freedoms, but when the individuals exercising those liberties come from outside the tribe, some people inside the tribe get worried. As one congressman put it, "With a porous southern border, we have no idea who's in our country." It's not what he knows that worries him; it what he doesn't know.

The congressman in question is Rep. Jeff Duncan (R–S.C.). I saw his statement in a New York Times piece about these ISIS conspiracy stories, where Duncan's comment came after a more clear-eyed remark from another congressman, the Texas Democrat Beto O'Rourke. "There's a longstanding history in this country of projecting whatever fears we have onto the border," O'Rourke told the Times. "In the absence of understanding the border, they insert their fears. Before it was Iran and Al Qaeda. Now it's ISIS."

So it ever was. In 1917, at the height of Romo's Brown Scare, the Los Angeles Times issued this warning:

If the people of Los Angeles knew what was happening on our border, they would not sleep at night. Sedition, conspiracy, and plots are in the very air. Telegraph lines are tapped, spies come and go at will. German nationals hob-nob with Mexican bandits, Japanese agents, and renegades from this country. Code messages are relayed from place to place along the border, frequently passing through six or eight people from sender to receiver. Los Angeles is the headquarters for this vicious system, and it is there that the deals between German and Mexican representatives are frequently made.

People were scared of Germany then; people are scared of ISIS now. Enemies come and go, but the dread that never disappears is the fear of the border itself.