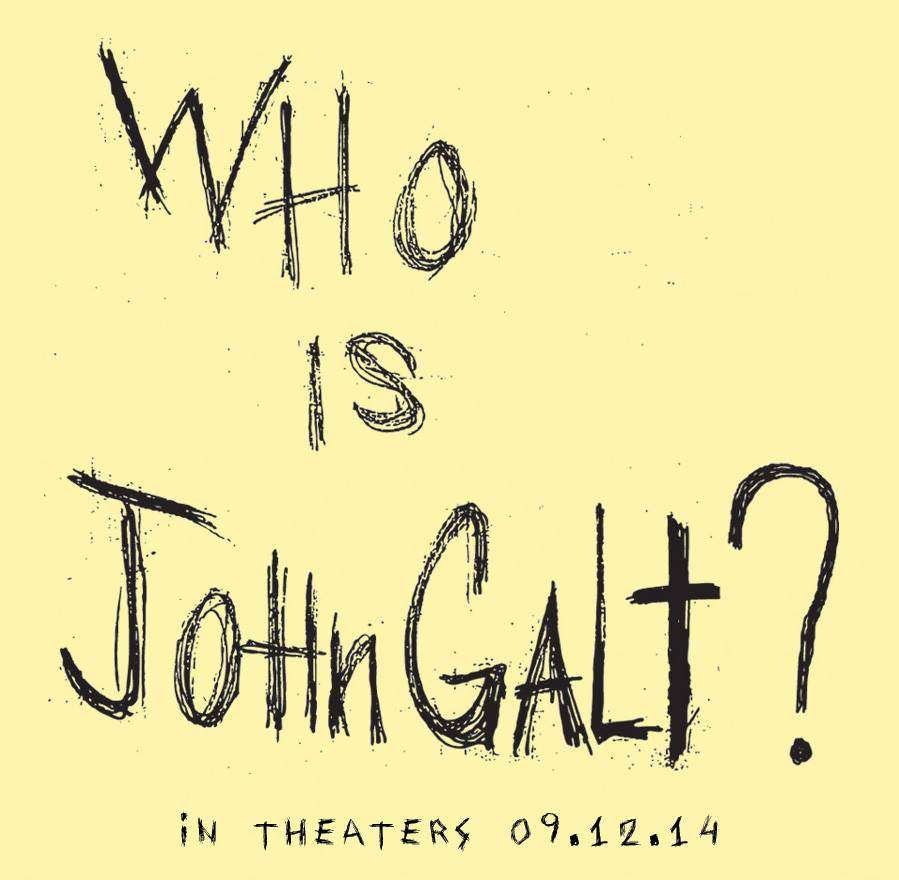

Kickstarting John Galt

A behind-the-scenes look at the third and final Atlas Shrugged movie

Last September, the producers of Atlas Shrugged Part III: Who Is John Galt? launched a Kickstarter campaign that ended up raising $446,000 to help fund the final installment of the film adaptation of Ayn Rand's 1957 novel about a world driven to the brink of collapse by overweening redistributionist government. The predictable response was cheap jokes from people whose (mis)understanding of Rand only went as far as: "She's that scary chick who valorizes businessmen and the market." Detractors assumed that asking people to freely support something they valued was altruistic and therefore un-Randian.

Producer and main financier of the trilogy John Aglialoro sees it differently. (As would anyone who understands Rand, whose novel The Fountainhead is a paean to an architect whose work goes unrewarded by the marketplace.) Rand believed in the glory of trading value for value—in this case, money for a film that the giver wants to see made. Aglialoro says he's proud of the hundreds of $1 contributions he received from people who he says told him: "I want to take some value of mine and place it where I see value."

Aglialoro is a successful businessman, named by Fortune magazine in 2007 as the 10th richest small business executive in the country. The first two movies in the trilogy were financial failures, losing him millions. So what's the business sense of plowing ahead? He says his latest project isn't primarily about money, but love.

Still, "we don't know that the trilogy will not make money," Aglialoro insists. "We know Part I did not and Part II did not." The combined production costs for all three will come to about $20 million, he says. "But I believe with this third piece-it's like a symphony. The adagio, what do you get out of it? It's boring to many people. They want the crescendo."

In an effort to drum up interest and cement their connection with the audience, the Atlas production team has been very transparent, creating a "Galt's Gulch Online" for supporters, inviting dozens of donors to visit the set, and frequently broadcasting live video from set during the shoot.

Associate Producer Scott DeSapio, who runs the film's online strategy, notes the novel has sold steadily for decades and still pulls in six figures in annual sales, "and you know how high the advertising budget is for that? Zero. It sells because people talk to people. And if we can make an Atlas that a [fan of the book] will feel comfortable recommending, then we've succeeded."

I visited the set in early February. For days the team had taken over the entire old Park Plaza Hotel near Los Angeles' MacArthur Park, transforming it into the Wayne-Falkland Hotel, into the scene of a dramatic press conference, into the apartment and lab of Atlas hero John Galt, and into a torture chamber where the bad guys keep Galt trapped.

And yes, to answer a question the Atlas team is weary of fielding, they did entirely recast Part III, just as they did Part II. "The star of the movie is not the actors," DeSapio says. "The star is the ideas of Ayn Rand."

The producers are high on new director James Manera, a veteran of the commercial world. "I think that if I were asked-and I won't be!-to form the curriculum of film school [on] what do you do to be a director," Aglialoro says, "I would say the graduate side should be knowing how to do a high-quality TV commercial. They have to get a lot of information and a lot of communication, a lot of art and visuality in that 30 seconds or 60 seconds, and Jim Manera has won awards in that world."

Dominic Daniel-playing Eddie Willers, the story's representative of a decent ordinary man-says that Rand's Fountainhead, which he'd been assigned in high school, "spoke about individuality, finding one's own path and taking responsibility for your own life and not listening to people who say 'you owe it to us,' is " a message that resonated as he chose a career in the arts instead of what his parents expected. He knows that curious feelings and hostility toward Rand's work exist, and admits he's gotten "a little of that" from suspicious friends. But "I didn't have any reservations," he says.

On my day on set, I watched for hours as they filmed the scene where John Galt's speech explaining the philosophical and ethical errors that lead society to its parlous state begins interfering with a planned televised address by America's national leader. Galt's speech is famously long-had they not condensed it, that one scene alone would have taken more time than most feature-length films.

Aglialoro thinks Rand was having an intellectual "bad hair day" when she decided to valorize the term selfishness. He thinks that word blunts her message of individual achievement through freely chosen market cooperation, not "self at expense of others." Thus, he tried to make the film's approximately four-minute condensation of Galt's speech more inspirational, less condemnatory, than the novel's version. It ended (from what I could hear) with talk of how you should not in your confusion and despair let your own irreplaceable spark go out, and how the world you desire can be won.

The most orthodox of Objectivists, like the ones associated with Rand's heir and enforcer Leonard Peikoff, will likely object. Aglialoro sums up his relationship with these controllers of Rand's estate from whom he bought the movie rights: "I wish them well-we share the same ideas-and they wish us extinction."

The financial prospects of the Atlas film remain uncertain-Part III isn't out until September. But Aglialoro says he never had any doubts that he had to finish what he started, regardless of potential profits and losses. Its "purpose," he declares, "is to change people's lives for the better," by helping them realize "the opportunity and responsibility of enlightened self interest."

Show Comments (113)