Why Won't California Release Innocent Men from Prison?

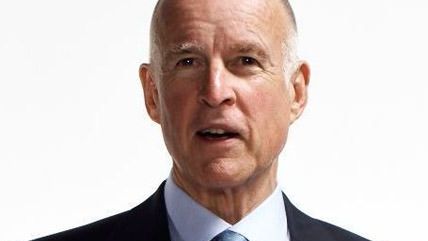

Gov. Jerry Brown has the power to exonerate them, but he won't use it.

SACRAMENTO — Gov. Jerry Brown and the legislature have been cutting down on prison overcrowding to comply with a federal court order, thus leading to a "realignment" policy that moves inmates from state-run prisons to county jails and a policy that may result in some early releases.

Whatever one thinks of the governor's handling of this matter, it's hard to understand why he hasn't pursued his prison-reduction efforts by harvesting some low-hanging fruit – i.e., releasing from prison those inmates who almost certainly are not guilty of the crimes for which they've been convicted. The governor, after all, has the power to grant clemency and pardons.

Why not act on the evidence surrounding the so-called California 12?

Those are the 12 California prison inmates whose cases have been investigated by the California Innocence Project, a legal clinic at the California Western School of Law in San Diego. The group has secured the exoneration of 11 California inmates. U-T San Diego in March reported on its client, Uriah Courtney, who served eight years of a life sentence for rape before DNA evidence pointed to the real perpetrator.

Each year, the school's legal team receives more than 2,000 claims from inmates. It brings to mind the line from the prison movie, "The Shawshank Redemption," in which one of the characters says, "Everybody's innocent in here. Didn't you know that?" But while many people claim to be innocent in prison, some of them actually are innocent. And while the numbers might not be large, the sense of injustice is overpowering.

"I'm pretty darn cynical," the project's director, Justin Brooks, told me after a Friday rally at the Capitol steps. Of the thousands of cases his team reviews, they usually end up with one or two. These are cases where he is 100 percent convinced of the inmate's innocence. But even when the evidence is strong, it's hard to get action on the cases.

Prosecutors aren't always cooperative when it comes to reviewing some of their possible past mistakes, although Brooks says that San Diego County District Attorney Bonnie Dumanis has been an admirable exception. She always sits down and looks at the evidence.

But the courts are reluctant to reopen a case unless there is some new piece of evidence or a new technology (i.e., DNA), he explains. If, for instance, the defense simply did a bad job or didn't call a witness who could have exonerated the defendant, then it's nearly impossible to get a new hearing.

For instance, one of the California 12 is Quintin Morris, who has served 17 years in prison for three counts of attempted first-degree murder, even though another man later admitted the crime. The court found that such a confession should have been presented at the trial and rejected efforts to free him.

As the Innocence Project explains on its website, "A federal judge noted that his hands were tied and he could not reverse Q.T.'s conviction because there were no 'legal avenues to do so.' The judge expressed serious concern over whether Q.T. committed the crime and suggested that Q.T. specifically apply for a pardon from the governor."

All of the California 12 cases are equally disturbing, and while Brooks says his group is pursuing legal avenues on all of them, their best hope remains petitioning the governor for pardons, as the federal judge has recommended in the Morris case.

So last year, Brooks and two colleagues marched 712 miles to the Capitol to get some publicity for their cause. And after another year of inaction from the governor, they came back to the Capitol and again tried to spark some publicity.

"We've had several conversations with the Innocence Project and their materials are being reviewed," said the governor's office, in response to my inquiry.

On the Capitol steps, I talked to Tim Atkins, who spent 23 years in prison for murder before being released after the Innocence Project found that the conviction was based on a faulty eyewitness report. He described his nightmare — one that finally ended with an apology and exoneration from the same judge who had sentenced him years ago.

"Any kind of injustice affects us all," Atkins said. Maybe if the cost-saving argument doesn't reach the governor, a simple ethical one might.

Show Comments (30)