The Third Lesson of Nelson Mandela

With great foreign intervention comes flawed moral reasoning.

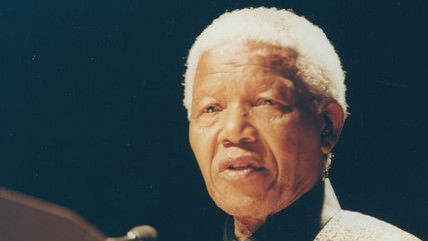

When South African prisoner-turned-president Nelson Mandela died on December 5 at age 95, commentators all over the globe wasted no time extracting two main lessons from the great man's life. One about persevering in the long struggle against injustice, the other about refusing to become embittered in the process.

Anyone fighting tyranny can take inspiration from Mandela's fierce, unwavering opposition to the race-based totalitarianism long practiced by South Africa's Afrikaner minority. As President Barack Obama said, "He achieved more than could be expected of any man." And Mandela's post-jail decision to reconcile with the regime that had persecuted him, rather than seeking vengeance, was one of the most stirring examples of power spurned this side of George Washington. "Nelson Mandela could have chosen to be-had the power to become-an even greater monster than [Robert] Mugabe," the conservative radio host Hugh Hewitt wrote just after Mandela's death. "Instead, Mandela chose to become a saint."

Saint will be too strong a word for the many Americans, mostly on the right, who remember less nostalgically Mandela's Cold War-era partnership with terrorism-supporting communists such as the longtime African National Congress (ANC) leader Joe Slovo, his affection for Fidel Castro ("Long live the Cuban Revolution! Long live Comrade Fidel Castro!"), or even his more recent statement, in 2003, that "if there is a country that has committed unspeakable atrocities in the world, it is the United States of America. They don't care for human beings."

In the globe-straddling ideological proxy war between the mostly free, capitalist-friendly, U.S.-led West and the mostly captive, communism-expanding, Soviet-led East, many Republicans believed Mandela chose the wrong side, both pragmatically and ideologically. "The release of Mandela," William F. Buckley wrote in 1990, "for all that we can know, may one day be likened to the arrival of Lenin at the Finland station in 1917." Five years earlier Buckley had proclaimed that "where Mandela belongs, in his current frame of mind, is precisely where he is: in jail."

Such sentiments, jarring as they are to our 21st-century ears, suggest a third lesson from Mandela's life: Massive American engagement with the fortunes of other countries, no matter how justified, is inherently corrupting. And not just for the William F. Buckleys of the world.

The American anti-apartheid movement of the mid-1980s, in which protesters demanded divestment and punitive economic sanctions, was arguably the biggest single foreign policy dispute in American politics between the end of the Vietnam War and the fall of the Berlin Wall. At my activist-heavy school, the University of California at Santa Barbara, observers said it was the biggest burst of political ferment since the bank-burning days of the early '70s. When both houses of Congress overrode President Ronald Reagan's veto of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, it marked the first time in the 20th century that an American president had suffered a formal congressional rebuke on foreign policy.

Although apartheid should have been viewed as a pretty simple, literally black-and-white issue of a majority brutally repressed by a minority, it was impossible in America to avoid seeing it through the lens of the Cold War. Consider a remarkable and controversial speech Reagan gave on the subject in July 1986, in which (among many other things) he called for the release of Mandela and the unbanning of black political parties.

Reagan launched his remarks with an unambiguous condemnation of state-sponsored racism. "The root cause of South Africa's disorder is apartheid, that rigid system of racial segregation wherein black people have been treated as third-class citizens in a nation they helped to build," he said. "America's view of apartheid has been, and remains, clear: Apartheid is morally wrong and politically unacceptable. The United States cannot maintain cordial relations with a government whose power rests upon the denial of rights to a majority of its people, based on race. If South Africa wishes to belong to the family of Western nations, an end to apartheid is a precondition. Americans, I believe, are united in this conviction. Apartheid must be dismantled."

Yet the first applause line of the speech, which came past the 12-minute mark, was this: "But the South African government is under no obligation to negotiate the future of the country with any organization that proclaims a goal of creating a communist state, and uses terrorist tactics and violence to achieve it."

That organization was Mandela's ANC, what Reagan called "the Soviet-armed guerrillas of the African National Congress." The administration could wave away the terrorism of Nicaragua's contras, since they were fighting a Soviet-friendly socialist regime, but because of geopolitics such tactics were apparently intolerable when employed by an even more oppressed underclass. "If [the] rising hostility in southern Africa between Pretoria and the front-line states explodes, the Soviet Union will be the main beneficiary and the critical ocean corridor of South Africa and the strategic minerals of the region would be at risk," Reagan said. "Thus it would be a historic act of folly for the United States and the West, out of anguish and frustration and anger, to write off South Africa."

Campus activists were fond of pointing out such hypocrisy, but they were equally guilty, if not quite as powerful. Those big anti-apartheid protests quickly morphed into broad left-bent critiques of U.S. foreign policy that included encomiums to Fidel Castro just as nauseating as Mandela's above. The same people demanding sanctions against South Africa in one breath condemned the U.S. embargo against Cuba in the next. Human rights abuses by Washington-favored regimes took up most of the oxygen, while the widespread, heavily documented totalitarianism of the communist bloc was routinely underplayed. As the Czech dissident Vaclav Havel acidly pointed out, Western European peace activists spent far more time protesting the deployment of U.S. missiles than they did protesting the Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan.

When you subject every local struggle to the with-us-or-against-us vicissitudes of international entanglement, everyone comes out warped. Even the participants. Successive Afrikaner governments quickly learned the value of talking up anti-communism and making sporadic references to free markets, so that official Washington would not be overly motivated to upend the status quo. Mandela and the ANC were happy to call for nationalizing industries and mouth the fraternal pieties of international communism if it meant more support in the struggle to topple their tormentors.

As former Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver put it in a 1986 reason interview, Mandela's "attitude was, Communism is better than apartheid. Because apartheid has him in prison and has had him in prison for 20 years. Well, you get a guy in a communist country who has been in prison there for 20 years, and he will tell you, 'I would rather live under apartheid,' because he could leave."

Much of this superpower gaming, and the mental distortions that came with it, ground to a halt with the end of the Cold War. It's no accident that so many proxy civil wars dried up in the early 1990s, or that Nelson Mandela stopped talking so insistently about the state owning the means of production. Although I have no doubt that an uncommon grace and wisdom guided his hand in giving "truth and reconciliation" precedence over righteous retribution, it is also true that the range of options narrowed rapidly once the Berlin Wall fell.

Eyes now relaxed, we can see Mandela more for what he was rather than what some feared he might be. He was a revolutionary-with all the crudeness that word implies-who fought for decades against an unjust, inexcusable regime, then smoothly negotiated its transition into something better, while managing to exercise his well-earned power by essentially giving it up. Hardly a saint, but definitely a hero. May we live in a world where Mandelas are no longer required, a world where our vision is no longer clouded by a teeth-clenched obsession with a twilight international struggle.

Show Comments (99)