Better Mental Health Care, Not New Gun Laws, Will Prevent Future Mass Shootings

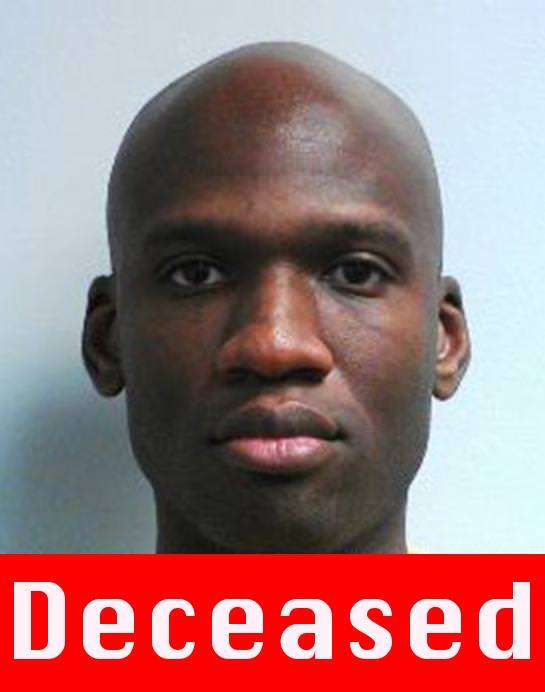

Aaron Alexis requested mental health help. Why are we answering with gun control?

Earlier this year, stand-up comedian and talk-show host Joe Rogan tweeted, "This country has a mental health problem disguised as a gun problem and a tyranny problem disguised as a security problem." As more facts come to light about the Washington Navy Yard shooting last week, it seems he hit the nail on the head.

On Monday, Sept. 16, Aaron Alexis, a 34-year-old Navy contractor and former reservist, went on a shooting rampage at Navy Yard killing 12 people, including himself, and injuring 14.

While the Veterans Administration insists Alexis sought help for insomnia only, it has come to light that Alexis reported hearing voices to police and claimed that three people were sending vibrations that kept him from sleeping. Alexis called police in Newport, R.I. to a Marriott hotel room on the morning of Aug. 7 to report that he was being followed and was worried people were going to hurt him.

This is in keeping with a history of erratic, criminal behavior. During a 2004 incident, Alexis used a .45 caliber pistol to fire five shots into a construction worker's car and one round into the air. In 2010 Alexis was arrested for firing into the apartment above him, nearly missing his neighbor's young daughter, allegedly because there had been too much noise.

Because he never indicated he planned to harm himself or others, a police officer's warning about Alexis was never communicated up the chain of command.

In theory, the Navy Yard should be free of both guns and the criminally insane. The base effectively strips personnel of weapons in the manner of most military bases. And working at the Navy Yard requires a security clearance.

Despite his history, Alexis entered the Naval Sea Systems Command headquarters on Sept. 16 holding a valid pass and secret clearance.

On Tuesday, Sept. 17, White House press secretary Jay Carney accused lawmakers who oppose expanded background checks for gun sales of taking cues from "a narrow special interest" instead of serving their constituents. These lawmakers may have read a Harvard study that found that the Americans have neither unique access to guns, nor a uniquely high murder rate, and indicated that gun ownership and murder rates are not positively correlated.

Making background checks mandatory and banning sales of the AR-15 is much easier than improving the way we screen for and treat mental illness. But, like most gun laws, new restrictions are unlikely to be enforced or to limit violent crime. Many of these proposals violate the rights of law-abiding citizens. Instead, lowering the threshold for mental health services, particularly by removing the requirement that an individual be an explicit threat to themselves or others before they receive help, can improve lives with zero rights violations.

Gun control enthusiasts have proposed laws which will make providing mental health services more difficult, such as a recommendation that would require states to make mental health information available to the federal or state agencies that perform background checks.

National Rifle Association chief executive Wayne LaPierre recommended a national registry of the mentally ill. Thirty-eight states already have such databases and federal law prohibits people who have been involuntarily committed or have been deemed a danger to themselves or others by a court from owning a firearm.

Already the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) has the Mental Defective File. Records in this file increased from about 90,000 to about 400,000 between Nov. 1999 and Nov. 2007. After the Virginia Tech shooting in 2007, Congress moved to allocate additional funds for states that agreed to share at least 90 percent of their mental health records with the federal government. Even with this incentive, there are not nearly as many records in the database as the law says there should be.

Not only is the information incomplete, and has so far been ineffective at stopping the mentally ill from obtaining firearms, but using this information to deny someone the right to own a gun can discourage others from seeking mental health help. Keeping firearms out of the hands of the mentally ill has not yet been achieved, and is unlikely to be achieved, in this way. Recording the fact that people are asking for help in a national database and then denying them rights on that basis will neither help them nor encourage them to seek treatment.

Alexis sought, and was denied, help before the rampage. Let's not fail his victims, or anyone in Alexis's situation, by avoiding our responsibility to help and instead implementing more toothless gun restrictions and recording more data at the federal level. If we spent time looking for ways to offer more and better assistance to those suffering from mental illness, rather than deny anyone their constitutional rights, perhaps we could reach a point where we have neither a mental health problem nor a gun problem.

Show Comments (124)