Homeland Security Meets Office Politics

The author of an infamous report on right-wing extremism tries to defend his work.

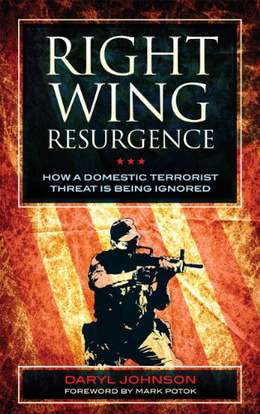

Right-Wing Resurgence: How a Domestic Terrorist Threat Is Being Ignored, by Daryl Johnson, Rowman & Littlefield, 400 pages, $45.

Idealist goes to the nation's capital, idealist produces notoriously shoddy document that his higher-ups refuse to defend, idealist gets snagged in bureaucratic politics, idealist leaves his job and becomes a government contractor. It isn't the usual narrative arc for a Washington book, but it might be a more typical Washington story. And while the author certainly wouldn't put it in the terms I used, it's the story underlying Daryl Johnson's Right-Wing Resurgence, the meandering memoir of the man who wrote the Department of Homeland Security's infamous report on right-wing extremism.

Johnson's paper set off a firestorm when it was exposed in 2009. The document seemed at least as interested in right-wing groups' ideologies as it was in their capacity for violence, a fact that set off civil liberties alarm bells. And a footnote gave the impression that the paper was casting its net pretty wide. "Rightwing extremism in the United States," it said, "can be broadly divided into those groups, movements, and adherents that are primarily hate-oriented (based on hatred of particular religious, racial or ethnic groups), and those that are mainly antigovernment, rejecting federal authority in favor of state or local authority, or rejecting government authority entirely. It may include groups and individuals that are dedicated to a single issue, such as opposition to abortion or immigration." This was widely construed to mean that anyone opposed to immigration, abortion, or federal authority was perceived as a potential threat.

In fact, the footnote was a sloppily phrased list of the ideas that drive different extremists, not a list of ideas that are supposed to be extremist in themselves. But you can't blame people for having trouble interpreting the paper. Its own author doesn't seem quite clear on what he wrote. "Perhaps the definition was poorly worded and too vague," he says at one point. But three pages later he is offended at a suggestion that the report was badly written, declaring that "great care had been taken in the wording." In the first chapter Johnson stresses that Homeland Security's concern was with "violent antigovernment groups and potential terrorists," adding that in hindsight his "definition of right-wing extremist should have incorporated the aspects of supporting, endorsing, and conducting criminal acts and violence." But later he relates his long struggle with the department's Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, which tried to add precisely that sort of language to the report before it was released. Rather than recognizing that the office had a point, the author gets defensive. "Extremism should not be limited to those groups or individuals solely involved in criminal, illegal, or violent activity," he argues. "Extremism has a much broader definition, because it is the phase that precedes terrorism. Extremism involves ideologies that facilitate individuals and groups toward violence and terrorism."

And what might those ideologies be? There's a telling passage where Johnson notes that another federal employee was involved in a Tea Party protest. After stressing that the Tea Party movement is not in itself extremist, Johnson comments that

there are extremist elements within it. Judging by his comments to the counterintelligence officer, it appears that this individual may have been part of the "fringe" element.

This individual allegedly remarked to the counterintelligence officer, "In case you see my face in any protest photos, I want you to know that I am merely exercising my First Amendment rights!"

Ponder the mentality that translates that sentence into a sign that you're dealing with an "extremist element." While you're pondering, remember that for Johnson, an "extremist" has views "that facilitate individuals and groups toward violence and terrorism."

Revealing little nuggets like that are scattered throughout the book, from a disapproving reference to "fanatical Americans obsessed with preserving their constitutional rights" to a list of allegedly "far right" news sources that includes the mainstream Republican hangout RedState.com. But what's most revealing is what doesn't appear here. Johnson shows no awareness that there might be a problem with his ideas about "radicalization"—the core concept behind almost everything he has to say about domestic terrorism.

Go to the website of DT Analytics, the consulting company that Johnson runs today. Warning that "Extremist ideology can be described as 'a poison' absorbed into a person's mind," the site describes a simple "path from extremist sympathizer to extremist activist to terrorist." It recognizes that not everyone goes all the way down that road, but it never acknowledges that more than two directions might be possible. The Oath Keepers, who Johnson regards as a particularly potent threat, are a "radical" group that may well draw someone away from violent schemes and toward the organization's strategy of nonviolent resistance. Similarly, militiamen who believe only in the use of defensive violence have a history of warning the police about militia members who seem interested in terror. The social and psychological dynamics here are extremely complicated, and they aren't easily contained by Johnson's simple model.

Nor does Johnson spend much time discussing the ways work like his might undercut his stated aims. The sociologist Amy Cooter, who was doing fieldwork within the Michigan militia movement when the news broke of Johnson's DHS report, writes that many "militia members were frustrated by the report, believing it equated them with neo-Nazis and terrorists. Several militia groups disallowed, albeit temporarily, media representatives and other members of the general public from attending their training functions." In other words, Johnson managed to make the militias more secretive and paranoid.

Johnson is pretty secretive and paranoid himself. He speaks biliously of people who leak official documents. When a writer at Talking Points Memo acquires and mocks an over-the-top DHS report on "ecoterrorists"—the report warns about such dastardly tactics as "organizing protests," "flyer distribution," and "sending continuous faxes in order to drain the ink supply from company fax machines"—Johnson emails his superiors to complain that the journalist "blatantly ignored the security warning and document-handling instructions clearly printed on the front page of this assessment"; he suggests that someone "look into the possibility of recourse against this individual." Johnson seems to believe he has the power to read anonymous leakers' minds: After his own report on right-wing extremism is released, he declares it "likely" that the person responsible "believed that the new administration, led by America's first African-American president, had a preconceived agenda to usurp the U.S. constitution, replacing it with a Marxist government." When legislators and the press start criticizing his paper, Johnson doesn't merely feel that he has been misinterpreted. He decides that his critics have "willfully directed and inspired others toward extremism." They accomplished this "through the creation of an imaginary enemy," he adds, never evincing awareness of the possibility that he is conjuring an imaginary enemy himself.

But Johnson's chief interest isn't leakers. It's relating every excruciating detail of the Department of Homeland Security's intra-bureaucratic politics. It is difficult to express how deeply dull these sections of the book are. Johnson seems intent on quoting each line of each email that has some bearing on his story, including such lively communiqués as "Please review and provide final clearance NLT 1800 hrs today, 25 March 2009. Thank you." Between these infodumps, the intensely repetitive narrative, and a large number of careless errors (at one point Johnson calls the Libertarian Party the "Liberty Party"), it's easy to suspect the book wasn't edited at all. But someone at the publisher's office seems to have looked at it, since there's a note from an editor to the author on page 214 that neither Johnson nor any subsequent proofreader seems to have noticed.

All the same, there's something inspiring about those mind-numbing tales of office politics. When the furor over the extremism report erupted, Homeland Security officials refused to defend the document, Johnson's team was "left floundering day-to-day without any meaningful work to do," and the department ended up adopting a new civil liberties and privacy review process. As far as Johnson is concerned, he's telling a tale of spineless bureaucrats succumbing to political pressure and snuffing out his valuable efforts. But if you remove the filter of the author's perspective, you'll see that what Johnson calls political pressure could just as easily be seen as popular protest working. Offended citizens rose up; an unelected bureaucracy backed down; a lousy approach to tracking terror threats took a blow. All we needed was a leak, some public outrage, and the ass-covering instincts of the civil service. Take heart, civil libertarians: If they cowered once, they can cower again.

Show Comments (59)