The New Jim Crow Laws

They sound egalitarian and humane, but these racially "neutral" laws have created an American apartheid.

Minority problems have always been an important part of the US sociological landscape. At different times different groups posed different problems. But somehow in the past the group problem vanished or at least caused little attention. Handicapped immigrants such as the Irish, Italian, Polish, Japanese, and Chinese assimilated, as a group, into America's great melting pot.

With group urbanization as a general benchmark, however, newer minorities—namely, blacks and Latins—have not "melted" as readily. This fact has given rise to considerable public policy discussion. Numerous legislative bills to further civil rights have been enacted. There have been thousands of cases of individual or class litigation. A plethora of federal, state, and local programs of one kind or another have been initiated, costing taxpayers literally billions of dollars. In addition, there are indirect nonmonetary costs, including the racial antagonisms generated through governmental policy to assist minorities. These antagonisms result from policies such as racial hiring quotas and the busing of children.

One of the saddest features of the problem is that society is coming to view the difficulty that today's minorities face in entering the mainstream of society as a manifestation of group incompetence. Hardly anyone acknowledges that many, if not most, of the problems encountered are due neither to group nor to individual incompetence but rather are due to the excesses of governments dominated by politically powerful interest groups. In order to see how minorities are handicapped by governmental policy, we need to recall some basic economic theorems that are probably known to most but are often forgotten in the analysis of race and public policy.

SCARCITY AND CHOICE

Economics is the study of the allocation of scarce resources among competing alternative uses. A key concept in that definition is scarcity (not shortage) which is defined as a set of circumstances in which human wants exceed the means to satisfy those wants. The means to satisfy human wants consists of the world's resources, which are finite. For all intents and purposes, however, we may consider human wants insatiable. It appears that no matter what a person has accumulated, he always wants something else. The significance of scarcity is that it requires that choices be made—for example, about who shall have rights to use available goods and services. There are a number of ways to decide the question of who gets what; violence, government fiat, gifts, and market allocation are among the alternatives. Most societies, including ours, employ a mixture of these methods.

Whatever the method selected to allocate resources over competing usages, choice implies sacrificed alternatives; when one chooses to spend for a house, one forgoes the alternative of spending those same resources for a car. The notion of choice and forgone alternatives permits us to make an important observation about human behavior, namely, the higher the cost of the forgone alternative to acquire an additional unit of an object of desire, the fewer will be the units actually acquired. Many will recognize this characterization of human behavior as the first fundamental Law of Demand, more formally stated: Whatever quantity of any good purchased at any particular price, a sufficiently higher price will induce any person to purchase less, or the higher the price of something, the lower will be its rate of consumption. The Law of Demand is general and applies to all goods (objects of desire) and all societies.

Human personal characteristics are objects of desire. People do exhibit preferences for physical and nonphysical human characteristics—race, sex, religious and political affiliation, height, weight, congeniality, beauty, and so forth. All of these preferences are subject to the Law of Demand: the lower the price to indulge a preference for a personal characteristic, the higher will be the rate of indulgence, and the higher the price, the lower will be the rate of preference indulgence. In our society there are a number of laws and institutions that lower the cost of racial preference indulgence. More significantly, these institutions also foster other kinds of preference indulgence that are disproportionately borne by disadvantaged people as a class. It is unfortunate that in many cases the stated intention of laws is to help disadvantaged or less-preferred people, but the effects are to reinforce the disadvantage they suffer.

In general there are two conditions, operating singly or in combination, that give rise to a higher probability of preference indulgence. One is that there be attenuated rights to pecuniary income. The second, which is a variant of the first, is that there be restrictions on voluntary exchange—legal agreements that permit a third party to dictate or sanction the terms of exchange. Minimum wage laws, labor laws, and licensing requirements are prime examples of such conditions. In considering the effects of laws that restrict exchange, it must be kept in mind, however, that a particular law can produce a racial effect without having a racial intent.

THE MINIMUM WAGE LAW

Federal and state minimum wage laws are acts of governmental intervention in the labor market intended to produce a pattern of events other than that produced in a free market. In practice, such legislation specifies a legal minimum hourly wage that is higher than the lowest wages that would have occurred under free market forces.

Although legislative bodies have the power to mandate a wage increase, they have not found a way to legislate a worker productivity increase. Further, while Congress can legislate the price of a labor transaction, it cannot require that the transaction actually be made. To the extent that the minimum wage law raises the pay level above the productivity of some workers, employers will predictably make adjustments in their use of labor. Such an adjustment will produce gains for some workers at the expense of other workers. Those workers who retain their jobs and receive a higher wage clearly gain. The adverse effects are borne by those workers who are most disadvantaged in terms of marketable skills, who lose their jobs and their income or who are not hired in the first place.

The effect is more clearly seen if we put ourselves in the place of an employer and ask: If a wage of $2.65 per hour must be paid no matter who is hired, what kind of worker does it pay to hire? (Actually, the cost to the employer is higher because, in addition to wages, he pays fringe benefits such as Social Security and medical insurance.) Clearly the answer, in terms of economic efficiency, is to hire workers whose productivity is the closest to $2.65 per hour. If such workers are available, it clearly does not pay the firm to hire those workers whose output is worth, say, $1.50 per hour.

The impact of legislated minima can be brought into sharper focus if we ask the distributional question, Who bears the burden of the minimum wage? As suggested earlier, the most marginal workers bear the heaviest burden. These are workers perceived by employers as being less productive or more costly to employ than other workers. There are at least two segments of the US labor force that share the marginal worker characteristics to a greater extent than do other segments. The first group consists of youths in general. They are low-skilled or marginal because of their age, immaturity, and lack of work experience. The second group, which contains members of the first group, are some racial minorities such as Negroes, who as a result of racial discrimination and a number of other socioeconomic factors, are disproportionately represented among low-skilled workers. Not only are these workers made unemployable by the minimum wage, but their opportunities to upgrade their skills through on-the-job training are also severely limited—for most people acquire work skills by working at "subnormal wages," which amounts to the same thing as paying to learn. For example, inexperienced doctors (interns), during their training, work at wages that are a tiny fraction of those of trained doctors. College students forgo considerable amounts of money in the form of tuition and income so that they may develop marketable skills. Low-skilled youths from poor families are denied an opportunity to get a start in life when a high minimum wage forbids them to pay for job training in the form of a lower beginning wage.

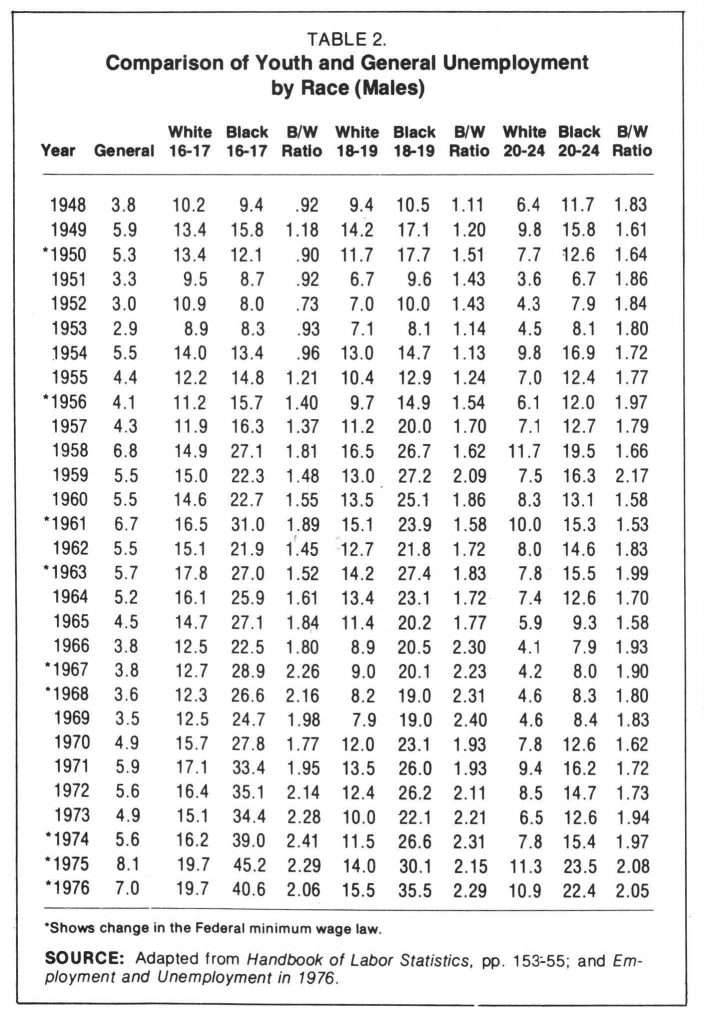

It is no accident that precisely these two segments of the labor force are also disproportionately represented in the unemployment statistics. Youth unemployment, even during relatively prosperous times, ranges from two to three times that of the general labor force. Black youth unemployment ranges from three to five times that of the general labor force and, for more than the last decade, has ranged from two to three times the unemployment rate for white youths. It is reported that in some metropolitan areas black youth unemployment exceeds 50 percent!

The economic effects of minimum wage legislation have been analyzed in sophisticated econometric studies. While there is some debate over the magnitude of the effects, the weight of academic research by economists points to the conclusion that unemployment for some population groups is directly related to such legislation and that the unemployment effects are felt mostly by nonwhites.

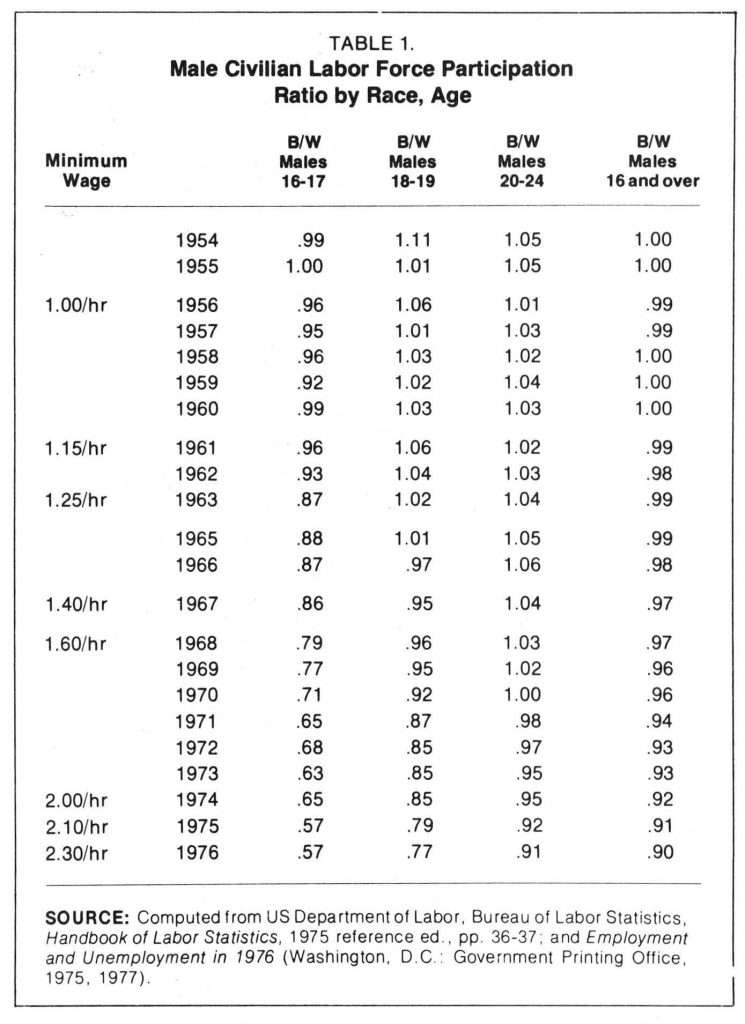

Most people are familiar with the more recent statistics on black youth unemployment, but not many are aware of black/white youth employment statistics for earlier periods, shown in Tables 1 and 2. In 1948, black youth unemployment was roughly the same as white youth unemployment. For that year, blacks aged 16-17 had a lower unemployment rate than did whites of the same age—9.4 percent compared to 10.2 percent. In the same period (until the mid-sixties), black youths generally were either just as active in the labor force or more so than white youths. By 1976, both the labor force participation rate and the employment rate of black youths had fallen dramatically.

Faced with these facts, one naturally asks, Why have labor market opportunities deteriorated so precipitously for black youths? Can racial discrimination explain this kind of reversal? Probably not. It would be very difficult to support the argument that employers have become more racist than they were in the past. The answer lies elsewhere—in the effects of the minimum wage law.

When a wage is legislated that exceeds worker productivity, firms will adjust their use of labor not only by hiring fewer youths but by seeking, among those youths hired, more highly qualified youths. For a host of socioeconomic reasons, white youths, more often than black youths, have better educational backgrounds and training. Therefore, the legislation of a minimum wage law can, as reflected in unemployment statistics, be expected to impose a greater burden on black youths than on white youths.

ENCOURAGING RACIAL PREFERENCES

The racial effect of the minimum wage law would exist in the absence of racial preferences on the part of employers. The minimum wage law gives firms effective economic incentive to seek to hire only the most productive employees. But holding all else (such as worker productivity) constant, it also gives firms incentive to indulge whatever racial preferences they may hold. The reason is that the minimum wage law prevents the less-preferred worker or job seeker from offering a compensating difference—that is, selling at a lower price.

To see how the minimum wage law can raise the probability of employment discrimination, we have to recognize that money profits are not the only form of compensation a businessman can earn. The return from business consists of a nonmoney component as well. That is, an employer, in addition to profits, prefers what he considers desirable working conditions—plusher carpets, finer furniture, prettier secretaries, more likable employees, etc. The quantities of "more desirable working conditions" that he chooses depend on the cost (price)—as predicted by the Law of Demand.

Suppose an employer has a dislike for blacks relative to whites. For simplicity, we assume that the workers who are to be employed do not differ except by race. If there is a law requiring employers to pay the same wage, no matter who is hired, then the employer can discriminate at zero cost. If there were no minimum wage, however, and blacks were willing to work for a lower wage, the cost to the employer to choose whites over blacks would be positive. The cost is the difference between the wages. The market would penalize such an employer because there would be firms that would hire blacks and, through lower production costs, tend to drive discriminating firms out of business. This line of reasoning is given additional weight when we recognize that even during relatively racially hostile times, black unemployment was less and labor force participation rates higher than in "racially enlightened" times. That is, to the extent that a black was willing to and was permitted to work for a lower wage than a white, there was a positive cost to the employer to indulge his racial preference.

The notion that it is sometimes necessary for some individuals to lower their price in order for some kinds of transactions to occur is offensive to the sensibilities of many people. These people support the minimum wage law as a matter of moral conviction, out of concern for equity in the distribution of wealth. These people should know, however, that white racist unions in South Africa have also been supporters of minimum wage laws and equal-pay-for-equal-work laws for blacks. In South Africa, black skilled workers in the building trades have been willing to accept wages less than 25 percent of those wages paid to white skilled workers. Such a differential made racial discrimination in hiring a costly proposition. That is, firms who chose to hire whites instead of blacks paid dearly—$1.91 per hour versus 39 cents per hour. White racist unionists well recognize that equal-pay-for-equal-work laws would lower the cost of racial discrimination and thus improve their competitive position in the labor market.

Unions in the United States are also major advocates of the minimum wage law. While US unions may have different motivations for their actions, we must remember that the effects of behavior are not necessarily determined by and may bear no relation to its stated intent. A good argument can be made for intent, however. Economists agree that for many activities low-skilled labor is a substitute for high-skilled labor. The market power of a high-skilled worker is influenced by the availability of substitute labor. If high-skilled workers can reduce or eliminate substitutes for their services, all else being equal, they can command higher wages. A numerical example will make this clear.

Suppose a fence can be produced by using either one high-skilled worker or three low-skilled workers. If the wage of high-skilled workers is $38 per day and that of an individual low-skilled worker $13 per day, the firm would employ the high-skilled worker because costs would be less ($38 versus $39). The high-skilled worker would soon recognize that his wealth would be increased by a minimum wage of, say, $20 per day in the fencing industry. The arguments the high-skilled worker would use to gain political support for such an arrangement would be those given by George Meany: "to raise the standard of living," "prevention of worker exploitation," "worker equality," and so forth. After the enactment of the minimum wage law, the high-skilled worker can now demand any wage up to $60 per day and retain employment. The effect of the minimum is to price the high-skilled worker's competition out of the market.

Whether the example given here accurately describes the motives of labor unions is not at issue. It is worth noting, however, that the restrictive activities that are promoted by unions do reduce employment opportunities and therefore the income of those forced out of the labor market. This fact suggests that, as part of union restrictive strategy, there must also be support for an incomes policy. Since large numbers without jobs and income represents a potentially dangerous political powder keg, unions have incentives to support income subsidy programs—welfare, Job Corps, summer work programs, the food stamp program, public service employment, etc.—for those denied job market access. Such income redistribution in effect constitutes a subsidy to those who have restricted the markets in the first place. Income maintenance programs disguise the true effects of restrictions created by unions and other economic agents, by casting a few "crumbs" to those denied jobs, thereby creating a permanent welfare class.

The increase in the minimum wage effective as of January 1978 will have serious unemployment consequences for youths. It has been shown that a 25 percent increase lowers employment of low-wage youths by 10-15 percent, which implies that the rise in the minimum wage from $2.30 to $2.65 per hour will decrease low-wage youth employment by 6.1-9.1 percent. This increase in youth unemployment could have been mitigated by the inclusion of a significant youth wage differential. If it wishes to bring more youths into the labor market, Congress should permit firms to hire youths at rates considerably less than the adult rate. Organized labor, however, is not even willing to permit this partial concession to economic reality, and the proposal to attach such a differential to the latest amendment of the minimum wage law was defeated in Congress.

Taxpayers are no doubt going to be called upon to support massive federal make-work projects to employ the nation's youth. Or, more tragically, millions of youths will become discouraged and permanently drop out of the labor force. Even worse, some of these youths will turn to various forms of antisocial behavior.

LABOR MARKET MYTHS

Before turning to some other restrictions that work to minorities' disadvantage, it is appropriate to comment on some widely accepted labor market myths.

• If teenagers are allowed to work at subminimum wages, they will be employed while their parents go unemployed. This is an example of the "lump of labor fallacy." It assumes that there is a finite number of jobs available, such that the acquisition of a job by one person of necessity requires that another lose his job. This is nonsense. After all, the number of people holding jobs grew from less than a million during colonial times to over 90 million today. All evidence suggests that this trend can continue. While there may be some substitution, the overwhelming effect of subminimum wages would be that of increasing total employment.

• The employment problem faced by youths and others is that there are simply no jobs available. If this myth is accepted at face value, it is the same thing as saying that all human wants have been satisfied, that no one anywhere wishes to have more of some good or service. Again, nonsense. The quantity of labor employed, just as any other thing of value, conforms to the law of demand; the higher its price, the less it is used, and vice versa. What people mean is that at some particular wage there are no jobs available. Nothing is strange about this observation, because at some particular wage anyone will find that his labor is not demanded.

• Many people are unemployed because they are low-skilled and have few qualifications. Low skills explain low wages, but not unemployment. A person is qualified or unqualified only in a relative sense—relative to some wage. A carpenter who is qualified, and hence employable, at a wage of $4 per hour may be unqualified, and hence unemployable, at a wage of $10 per hour. This idea applies to anything. A Sears suit is "unqualified" to sell for the same price as a tailored Pierre Cardin suit. Of course, if an organization of carpenters can through legal institutions require that employers pay all carpenters hired a wage of $10 per hour, they artificially disqualify and make unemployable the carpenter who was formerly qualified and employable at the wage of $4 per hour.

The notion of artificial disqualification has direct application to the problem that minorities face in the labor market. Would anyone be prepared to argue that blacks during earlier times had more education and training than blacks in present times and that is why they had higher employment rates? No, the real reason is that through the political mechanism (perhaps without intent) many blacks have been artificially disqualified.

• High youth unemployment reflects the "baby boom" of the post-World War II era. This myth reflects a misunderstanding of the basic laws of supply and demand. Given a demand, an increased supply of labor (or for that matter anything else) results in lower prices in a free market. It just happens that the labor market in the United States is not free.

• Widespread automation is the cause of high unemployment rates among a large sector of the labor force. This myth reflects both a kind of amnesia and the lump-of-labor fallacy. First, higher wages are the cause of automation. When wages rise relative to capital costs, firms have incentives to substitute capital for labor. For example, when elevator operators negotiated a higher wage, a few years later we saw widespread installation of automatic elevators; as grape pickers negotiate higher wages, we see the transition to grape-picking machines. Second, this myth is the lump-of-labor fallacy because it asserts that society has no use for the labor displaced by automation.

These labor market myths have maintained their popularity down through the ages primarily because they have been self-serving for particular interest groups and because many people are decent and have legitimate concern for their fellow man. Truly compassionate policy, however, requires dispassionate analysis, which shows the error of these and other labor market myths.

UNIONS AND MINORITIES

To understand the impact of labor unions on minority employment opportunities requires a brief discussion of the sources of union power. The typical person views the union's struggle for higher wages as a conflict where employers are on one side of the battlefield and employees on the other side. Created by labor unions, this myth is revealed as such when we analyze the causes and sources of union power.

The ultimate source of unions' power stems from their ability through the strategy of strikes to deny labor services to individual employers or whole industries. Union strikes, as a tool of negotiation, will be effective only if unions can control all potential workers of a particular firm or industry. Without this kind of control, a firm struck by a union could simply replace union workers with nonunion workers, thus reducing unions' power to force wages to a level higher than that dictated by the market.

Therefore, union power primarily rests on its ability to coerce and collude against fellow workers. Coercion is necessary because not all workers will find it in their best interest to support union activity. Higher wages secured by the union will give firms inducement to hire less labor, and those workers who would be unemployed as a result will have little incentive to support union activity. This means that strictly voluntary unionism could not win the support of all workers because those workers who would be unemployed as a result of higher wages would agree to work for a lower wage. Therefore, to achieve their principal aims unions must obtain complete control over the supply of labor to a firm, for which purpose there are a number of methods.

• Moral suasion. One way that control is achieved is through psychological and moral pressure that promulgates the erroneous belief that union activity benefits all workers. As seen above, it does not. A related aspect to this method of achieving control is the creation of the myth that unions have raised the standard of living to a level otherwise unattainable. Unions frequently point to periods in history in which wages were low and working conditions poor, but they fail to acknowledge that during the periods to which they refer worker productivity was also low. Technological progress that enabled workers to have higher productivity led to the gradual improvement in both pay and working conditions.

• Closed shop. In some areas of employment there are closed shop union agreements whereby employers are allowed to hire only those workers who are union members or are acceptable to the union. In other areas of employment there are union shop agreements whereby an employee need not be a union member to initially get the job but must become a member within 30 to 60 days. Both of these arrangements contribute to the maintenance of effective strike power in that the union has control of the labor supply.

• Violence. Force, the threat of violence, and intimidation are other ways that unions force recalcitrant employees and employers into line. History is replete with episodes of union violence, and the courts have sanctioned activities that would have been considered criminal if done by the average citizen. For example, in Apex Hosiery v. Leader (1940), the Supreme Court held that a striking union could seize a company's plant and stop outgoing hosiery shipments without violating the law. The court said that the restraint imposed by the union was only incidental to the legitimate purpose of advancing the union's own interest.

If unions are effective by these methods, wages will tend to be higher in the unionized sector. Naturally, workers will be attracted to the higher-wage sector. Therefore, unions will be faced with a flood of would-be union members. If unions offered membership on equal terms to all workers, they could not maintain the higher wages that they won and at the same time have all of their union members employed. Therefore, the union must devise a rationing system for membership.

First, it must be recognized that union membership rights are not sold on the market to the highest bidder. Thus, union membership will be based on noneconomic criteria. Noneconomic or personal characteristics of the worker that unions can employ to ration membership, include race, sex, political affiliation, age, education, experience, and personality. Unions also use probationary periods as a way to ferret out those workers who may be prone to violate union codes of conduct. This, too, restricts entry to the union.

UNION DISCRIMINATION

Even a cursory review of the labor movement in the United States demonstrates how organized labor, with but a few exceptions, sought to exclude Negroes and other minorities from many job markets. Exclusionary devices have ranged from union charter provisions that restrict membership to "white only" and violence against minority workers, to collusive licensing agreements between labor organizations and the State. In fact, past Negro leaders almost unanimously condemned unions. Booker T. Washington was a life-long foe of trade unions, and W.E.B. DuBois called them the greatest enemy of the black working man. Union discrimination against minorities needs no documentation here. Instead, we need to understand how our labor laws and institutions make union discrimination more likely and more costly to minorities.

The 1935 National Labor Relations Act gives the government's sanction to several practices in addition to those mentioned earlier that produce a racial effect. The practices that tend to be the most discriminatory are those exemplified in the contract construction industry, namely—

• Subcontracts. Construction contracts are generally let to one or two general construction contractors. These contractors usually subcontract their work out to specialty contractors who hire their labor from union hiring halls.

• Union referral. Most workers in the construction industry have no seniority with a single employer as such. Workers are hired by one employer, and after the job is finished they return to the union hiring hall for a new assignment.

• Territorial and work jurisdiction. Each craft union has jurisdiction that places limitations on the type of work and numbers of men assigned to a project; for example, a carpenter is not allowed to operate an elevator. Employers (contractors and subcontractors) are allowed to hire workers only from or through the union having the work and territorial jurisdiction.

The laws and customs in the contract construction industry also permit contracts to provide that unions have the first opportunity to fill job vacancies and that preference be given to employees employed in the industry before a certain date, to graduates of training programs operated by the union, and to "qualified workers."

These arrangements in the construction industry (particularly in force in the commercial building sector of the industry) make exclusion a quite likely, low-cost, and easily policed activity. Moreover, the existence of the union referral system makes it difficult for employers to hire minority employees while at the same time honoring their collective bargaining agreements with contract construction unions. Where employers are permitted to hire workers independently of union hiring halls, in order to comply with federal affirmative action requirements, minority craftsmen are often given only work permits by the union that sanctions employment. These permits do not entitle the worker to union seniority rights, pension, and other work benefits.

The fact that unions discriminate against Negroes, in and of itself, would not be an important determinant of economic opportunities for Negroes. What is important is the politically obtained union power to use government coercion to enforce the exclusion of nonunion members from particular parts of the job market. That is, if unions could not control access to jobs, the fact that they discriminate in membership would mean little to minorities.

LICENSURE

Entry into certain occupations is regulated by law. Licensure laws and certification requirements, though having some social merit, nonetheless act to limit entry to occupations and hence reduce employment opportunities. They thus constitute yet another form of market entry restriction that produces effects disproportionately borne by youths, minorities, and other disadvantaged people. Market entry restrictions by licensing are rife in the American economy. The taxicab and trucking businesses provide examples of the effects of such restrictions on economic opportunities for minorities. Neither has high initial capital costs relative to other undertakings, and neither requires high skill levels. Therefore, the only reason for a relatively small minority participation in these activities is the artificial barriers to entry.

In the taxicab business, entry is restricted through often prohibitively high legal requirements. For example, in New York and Boston, a license fee, which sells for $42,000 and $25,000 respectively, must be purchased for each vehicle operated as a taxicab. In Philadelphia, a certificate is required. The Board of Commissioners, in Harrisburg, sits to decide whether or not to issue a certificate based on whether they think the community "needs" more taxi service. For the last few years, they have decided that Philadelphia already has adequate taxi service, because they have not issued a single certificate. In Los Angeles, the city used to grant Yellow Cab Company an exclusive franchise whereby no other taxicab company could pick up passengers within the city limits.

In Washington, D.C., the story is quite different. Fee requirements are nominal—less than $200. As a consequence, Washington has more taxis per capita than any other American city, the price of taxi service is low relative to other cities and the service received by patrons better, and black taxicab ownership is high relative to the black population.

Another potential business for minority entry is the trucking industry. Here too, however, there are significant entry restrictions. To own and operate a truck for the interstate transportation of goods requires that one receive a certificate from the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC). A certificate will be granted if the entrant can prove that he can provide a service that no other trucker is currently providing. If the entrant only offers to provide a better service at cheaper prices, he will be denied a certificate. In a recent Illinois crackdown on truckers transporting goods without having certificates, the majority of those arrested were black truckers. Additionally, the fact that there are very few blacks licensed to be common carriers (though some have applied) points up the adverse racial effects of the regulations in the trucking industry.

The market entry restrictions cited here, and in general, are not racial in their stated intent. To the contrary, the stated intentions are those of high social "ideals" such as "orderly markets," "fair prices," and "fair returns." Whatever the stated intentions of the regulations, the effects are racial to the extent that these market restrictions discriminate most against latecomers, poor people, and those without political clout. Minorities are disproportionately represented in such groups.

STRATEGIES

There are many other areas of economic and social life where the law, "the rules of the game," produces adverse effects for minorities. Housing, education, and police services come to mind. Enough has been said, however, to demonstrate that certain racially "innocent" laws spell disaster for some segments of the population. The attribute that is common to all of these laws is that they place restraints on voluntary exchange in a way disadvantageous to minorities.

In the light of some of the government-sanctioned restraints discussed here, perhaps one of the best strategies to raise the socioeconomic status of Negroes as a group is to promote a freer market. The welfare of minorities can be improved if fewer of the decisions influencing their daily lives are made politically. One must recognize that in the political arena the decision-making criterion approximates majority rule. Almost by definition, competition in the political arena is such that a minority group is going to be most handicapped. While occasionally the majority will take measures that will benefit minorities, I suspect that most often the majority will act in ways that it perceives as being in its own best interest, which may not coincide with minority interests.

The market system, on the other hand, is essentially one-man-one-vote. While people may have unequal amounts of dollars, each person's one dollar has the same power as another person's one dollar. In the marketplace there is relative parity, which is nowhere more clearly seen than in the housing market. Many areas of many cities were once affluent, all-white neighborhoods and are now predominantly occupied by blacks. Virtually no one ever stops to ask the question, How did blacks take over these housing resources? It was through the market. Blacks simply outbid whites for housing. That is, for example, blacks told landlords that they would pay $100 per unit for a house separated into four parts, yielding the landlord $400 per month on a building that he was formerly renting as a single-family dwelling for $200. While one may have moral reservations about the market method of the allocation of housing for blacks and poor people, consider the alternative. Taking only the years 1967-71, government housing programs destroyed 538,000 units of housing. They replaced 201,000 units. Of the number of units replaced, less than half were for low- and moderate-income families. What the housing policy did do was to increase housing for high-income people and increase the amount of land available for office space.

Looking at any set of statistical data, we see that absolutely and relatively the free housing market has provided more housing for the poor than all government housing programs put together. Furthermore, the competitive market has done more to break housing discrimination than any government edict; witness how difficult it has been to prevent neighborhoods in our cities from changing from all-white to all-black, even during times of virulent racial discrimination. (Blacks and other poor minorities cannot obtain housing in the suburbs as easily because of political restraints to subvert the operation of the market, such as zoning laws requiring minimum-size lots and houses and requirements that units be single-family units.)

Many other examples can be given of how minorities are less disadvantaged when the allocation of resources occurs through the market as opposed to a political mechanism. The reason for this advantage is that personal characteristics play a smaller role in the market arena. The most tragic thing about the failure to recognize this fact is that the failure of a large percentage of Negroes and other minorities to "melt" into America's melting pot is attributed by many members of society to group incompetence. Hardly anyone lays the responsibility for this problem where it belongs: to the excesses of government controls. I would guess that if we abolished the minimum wage law, reduced licensing restrictions, changed labor legislation, and reorganized the delivery of education, in 20 to 30 years hence there would be no "Negro problem"—as there is no Japanese, Chinese, Jewish, or other earlier-immigrant problem. These people were able to start off poor and progress because they did not face the market restrictions that constitute Uncle Sam's apartheid.

Walter Williams is professor of economics at Temple University. This article is adapted from Policy Review, by permission of the author and the Heritage Foundation.

Blacks and the Market

Not too many years ago, the NAACP probably would have repudiated Walter Williams' conclusion that many governmental policies hamper, rather than help, minorities—but not today. The Black Caucus in Congress may continue to toe the standard liberal, welfare-state line; but elsewhere, changes are under way.

In January 1978 the 70-year old NAACP not only took a stand against the Carter administration's energy policy but announced a new direction: henceforth it will look at public policies, present and planned, with an eye to determining their effects on blacks' well-being and economic growth. The flurry of media reactions was almost more interesting than the NAACP's move itself. According to various reports—and accompanying cheers or hisses—the NAACP had defected to the libertarian/conservative side by embracing the free market or had ("obviously") been coopted by big business. Apparently, neither story holds up. The NAACP's January statement opposed Carter's energy program for being conservation- rather than growth-oriented and maintained that economic growth is in blacks' long-run interest; but it did not take a specific position on oil and gas price deregulation, nor did it flash the free market banner per se. And, while several members of the NAACP's energy committee work for energy companies, only one percent of the association's contributions come from such companies; only ten percent, from business in general.

The really significant fact is that the NAACP has declared its independence of the liberal-labor coalition and has decided to focus on economic issues. As Chairman Margaret Bush Wilson said to a Wall Street Journal editor, "It all comes down to economics. We don't know much about it yet, but we're going to find out." Walter Williams reminds us that passionate concerns—about the plight of minorities, for example—require "dispassionate analysis." Perhaps the liberal reaction has been one of dismay because the liberals have good reason to suspect that solid economic examination will show the superiority of the free market.

The American Association of Blacks in Energy has also registered its opposition to current governmental proposals for energy consumption and production. Black professionals and executives in the energy industry formed the AABE (financed by its members) in 1977 in response to the Congressional Black Caucus' cool reception of the views of a number of the AABE's members.

In a statement picked up in the February 16 Wall Street Journal, AABE Chairman Clark R. Watson detailed what he unhesitatingly referred to as facts—that government programs directed toward minorities have "failed dismally"; that black professionals are nowhere to be found in the Department of Energy, in contrast to the private energy sector; that federal programs discouraging domestic production of oil and gas shrink business and employment opportunities for blacks. Yet these plain facts go unappreciated by "certain national organizations purporting to represent blacks in service or elected capacities." These organizations take advice from outside the black community, and that advice, Watson notes, "usually comes from persons whose careers are dependent on welfare/socialism types of programs and who feel threatened at what they see as an eroding source of power-their 'poor minorities.'"

Watson's conclusion is strong indeed. "Economic parity for black Americans," the AABE's prime goal, "can only be accomplished with the existence of a healthy, vibrant free marketplace uninhibited by artificially low and unrealistic pricing schemes which only prolong the day of reckoning. These are facts."

—The Editors

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The New Jim Crow Laws."

Hide Comments (0)

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Mute this user?

Ban this user?

Un-ban this user?

Nuke this user?

Un-nuke this user?

Flag this comment?

Un-flag this comment?