Rockefeller's Draconian Drug Law

Four years, $141 million, and 2,000 life sentences later, New York has more drugs and more addicts than ever before.

"The really serious results of this legislation…will only appear gradually and will not always be recognized as such. These will be the failures of promising careers, the disrupting of happy families, the commission of crimes which will never be traced to their real cause and the influx of many who would otherwise live socially competent lives into hospitals for the mentally disordered."

—"New York Medical Journal," May 17, 1917, commenting on the first drug prohibition law, the federal Harrison Act.

Sometimes a single incident, a matter of seconds, can sum up a condition more eloquently and powerfully than reams of theory, argument, and statistics. Here's such an incident:

The scene is The Pit, a street corner along Eighth Avenue in Harlem. There are more than 600 persons on the corner, a bustling display reminiscent of the floor of the stock exchange. Above the din is heard the shouting of esoteric names.

"Malcolm Green!"

"The Judge!"

"No-Monkey-Business!"

"No Respect!"

These are brand names. Of illegal drugs.

Now through this crowd of busy shoppers comes Sterling Johnson, Jr., New York City's special narcotics prosecutor, with police aides. The entrepreneurs and their customers know Sterling Johnson. He is The Man. But they continue conducting business. The sellers are openly soliciting motorists, sometimes pushing their wares in through the window to give drivers a closer look. They are aware of The Man walking in their midst. They don't care.

Then one of them approaches Johnson. He scowls. "Man, get off the fucking street corner if you ain't here to buy dope." The angry drug dealer walks on.

This occurred in 1976 more than three years after New York State enacted the harshest drug laws in the United States, laws mandating indefinite life sentences, severely restricted plea bargaining, and lifetime parole for drug sellers.

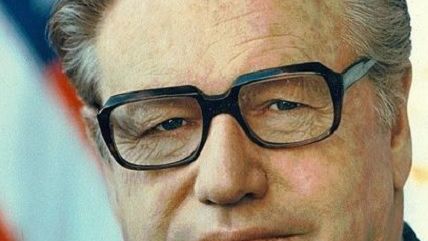

If one is wondering how the laws (called the Rockefeller laws because of their instigation by then Gov. Nelson A. Rockefeller) have worked, the answer is to be found in that incident. For when all the statistics are sifted, all the bills tallied, all the pros proffered and cons considered, rising from the rubble of paperwork are that incident and its inescapable message: today, after some 2,000 persons have received indefinite life sentences for selling illicit substances, it is as easy to get drugs in New York City and other parts of the state as it was four years ago and more than $141 million ago. It's probably easier.

The narcs concede it. So do the politicians and administrators of "criminal justice." New York City newspaper reporters almost routinely go out looking for drugs just so they can tell their readers how easy it is. With all the reporters and undercover agents in those crowds, it's a wonder there's anything left for the drug users.

In 1973, the popular estimate of the habitual hard-drug-user population in New York City was 150,000 to 300,000. It seemed a safe enough range, but some researchers thought it was low. Richard Ashley, in his 1972 book, Heroin: The Myths and the Facts, conservatively put the estimate at 360,000. This was before the enactment of the nation's toughest drug laws.

In 1976, according to the N.Y. Office of Drug Abuse Services, there were 230,530 "narcotics addicts" statewide and another 333,570 "abusers of non-narcotic drugs," including cocaine, glue, amphetamines, barbiturates, tranquilizers, and LSD.

There are good reasons to assume that official bodies tend to underestimate such things. For one, counting drug users is not an easy task. By definition, it is counting criminals. Sterling Johnson, again keeping a safe span, estimates the current New York City "addict" population to be from 400,000 to 800,000.

Add to this the reported sharp increases in serious crimes throughout New York City and we must ask, What happened? Why aren't those numbers smaller rather than larger? Why didn't the Rockefeller laws turn the drug problem around once and for all? And can anything succeed where they failed?

The laws that bear the former vice-president and governor's name made their way onto the books powered by flames of hysteria—a blaze fanned frantically by Rockefeller himself. Comparing drug users and sellers to an "invading army," he said the defenses of civilization were almost exhausted and that to save our lives and way of life we must resort to the last defensive maneuver available.

Drug-crazed and profit-hungry criminals were rampant in the streets. Nothing less would do. In a televised state-of-the-state address to the legislature in January 1973, Rockefeller called for mandatory life imprisonment for drug sellers. No plea bargaining. No easy sentences from lenient judges. No parole. No youthful offender treatment. Life in the slammer. Period.

A billion dollars' worth of treatment had failed to cure this "disease" and cut crime, Rockefeller said. It was time for something new.

Immediately, speculation began as to why the governor was doing this. Some people, mostly professional "rehabilitation specialists," pointed out that the massive treatment programs begun during Mayor Lindsay's years were showing signs of success and that Rockefeller's proposal was an unjustified regression. (On this point, Rockefeller was closer to the truth; the rehabilitation workers had an interest in maintaining otherwise.)

It was noted that Rockefeller was up for reelection in 1974 and was a presidential aspirant for 1976. The nation's Nixonian mood, so went the theory, made it mandatory for a political hopeful to appear tough on drug users and crime. Rockefeller, burdened with a liberal image within the Republican Party, proposed the laws in his lurch to the "right" as he prepared a presidential bid.

CRITICS GALORE

Whatever the reason, the laws were proposed, spawning an unlikely coalition of opponents that included the American Civil Liberties Union, Mayor Lindsay, the state District Attorneys Association, the Conservative Party, the state Judicial Conference, and the police. Months later, when signing the bill, Rockefeller would call the coalition a "strange alliance of vested establishment interests, political opportunities and misguided softliners who joined forces and tried unsuccessfully to stop this program."

The opponents said that a law with mandatory life sentences and no plea bargaining would overwhelm the courts and prisons. They said, perhaps contradictorily, that juries would be reluctant to convict defendants if the penalty was so harsh (this reportedly had been the experience elsewhere). The district attorneys and judges objected primarily because it would take discretion from them.

There were critics who predicted that stepped-up enforcement and harsher penalties would increase the risk of drug dealing and hence the profits, inviting more, not less, illicit trade. If the laws succeeded in cutting drug supplies, it was argued, more crime due to rising prices could be expected.

It was even suggested that if the maximum penalties for murder and drug selling were the same, it would be a riskless venture for an accused drug offender to attempt to kill the witnesses against him. (The penalty for murder would actually be less severe because a murderer can plea bargain without legal restriction and be discharged from parole. At the time of the debate, eight of ten convicted or confessed murderers got sentences of ten years or less.)

But most of all, opponents claimed that the bill failed to distinguish between the big drug dealer (the capitalist) and the lowly user-seller trying to support his habit. It was predicted that high-level dealing would remain untouched.

Invectives were heaped on Rockefeller and his brainchild. "Barbaric," "inhumane," and "ignorant" are just some of the labels that turned up in the press. State Supreme Court Justice James J. Leff remained ironically optimistic. "The madness will pass," he said.

To those who agreed with the spirit of the law but doubted its practicality, Rockefeller said, "I am totally intolerant of the position that we should not protect the people because it won't work in our system."

Despite the outcry of opponents, the legislature went along—but not without substantial changes. The bill that was signed in May 1973 allowed limited plea bargaining, the possibility of lifetime parole after a mandatory minimum jail term, possible lifetime probation for informants, and the removal of hashish from the dangerous drug list.

In anticipation of a case-load increase, the legislature created new judgeships and other court resources that by the end of 1975 had cost the taxpayers $55 million. The state ran a $500,000 promotional campaign before the law went into effect on September 1, 1973, to scare users into treatment programs. ("That didn't happen," said Irwin Davidson of New York City's Addiction Services Agency.)

Before describing the "draconian measures," as the newsmagazines called them, it might be interesting to consider part of the historical backdrop against which the Rockefeller laws were set.

WHAT THE LAW CHANGED

By 1973, mandatory jail terms were out of vogue. New York State and the federal government had both abolished them for various crimes because they didn't deter criminals.

In 1966 and again in 1970, Governor Rockefeller had declared "all-out war" on drugs. In these efforts, he got minimum jail sentences raised for the first time since 1951, and the legislature approved huge amounts of money for treatment programs, which included compulsory three-year civil commitments for habitual users. Rockefeller estimated that between 1963 and 1973, almost $1 billion was spent in the anti-drug effort. Presumably, the all-out wars were lost.

One more thing about the pre-1973 period: judges already had the power to sentence large-scale drug dealers (those selling a pound or more) to life imprisonment. This gives credence to the view of Dr. David Musto, the Yale psychiatrist and drug-law historian, that the law actually was aimed at allegedly lenient judges who were considered wrist-slappers by some law-enforcement officials.

In essence, the Rockefeller laws restructured the sentencing statute and realigned the drug quantities to which it applied.

The sale or possession of any amount of "hard drugs"—opiates, LSD, cocaine (which the law mistakenly calls a narcotic), and others—carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. The judge has no choice but to impose life in prison as the maximum term. The minimum term varies from 1 to 25 years depending on the quantity at issue. But some time in prison must be served. Parole, if granted (there are no set standards), is for the rest of the defendant's life (to appreciate the severity of this, consider that a parolee may not even marry without permission).

The law at first contained severe plea-bargaining restrictions. No one indicted for a drug felony that carried a life sentence could bargain to a charge with a minimum sentence less than life. The three classes of drug felonies with indefinite life sentences have different minimum terms based on a descending table of quantities: A1, A2, and A3. Under the bargaining rules, persons charged with A1 (minimum sentence: 15 to 25 years or A2 (6 to 8 1/3 years) could bargain down to A3, which has a minimum between 1 and 8 1/3 years. But someone charged with an A3, the least serious of the "serious" offenses, could not bargain at all because the maximum had to be life.

The outcome of this was as predicted. A3 defendants went to trial in droves because they had nothing to lose. The result: an eight-month backlog in New York City by the end of 1975.

Here is how the law was assessed in the September 1976 report of the Drug Law Evaluation Project of the New York City Bar Association: "During the first two years the new drug and sentencing laws were in effect, none of the key indicators of successful implementation have been evident.…Both in 1974 and 1975, there were fewer dispositions, convictions and prison sentences for drug offenses in New York State than there were in 1973."

The inability of the courts to handle the trial load eventually led the legislature to amend the restrictions on plea bargaining so that A3 defendants could avoid a life sentence by accepting 1 to 15 years instead. With this incentive to plead guilty, 1976 saw an improvement in the court's efficiency.

Other methods were unofficially adopted to avoid paralysis of the court system. Before 1976, unrestricted pre-indictment plea bargaining was common, though it circumvented the law. Former Manhattan District Attorney Richard H. Kuh got around the law by allowing illegal sellers of methadone to plead to a misdemeanor, although the law treated it as a heroin sale. (The methadone provision was especially harsh because New York State uses an aggregate weight standard, meaning that a trace of methadone in an ounce of orange juice is treated as an ounce of methadone. The courts finally ruled that the equation of methadone with heroin was unconstitutional because methadone is distributed legally by the government.)

Other methods of weakening the effects of the law were implicitly adopted for so-called sympathetic cases, for instance, a woman with children who helped her boyfriend sell heroin but made no profit. A New York City attorney said a minority of city judges used "sleight-of-hand and off-the-record agreements" to get charges reduced or dismissed. "Essentially," said one of the judges, Leon Polsky, "a judge resists any law which requires him to impose a particular sentence."

No major provision of the Rockefeller law has been rejected by the courts. In 1975, the State Court of Appeals ruled the life sentence constitutional. But, in an interesting aside, Chief Judge Charles Breitel wrote that the sentences' "pragmatic value might well be questioned since more than a half century of increasingly severe sanctions has failed to stem, if indeed has not caused, a parallel crescendo of drug abuse."

STREET RESULTS

In judging whether the Rockefeller law has worked, one needs a standard. It is tempting to look to statistics; so officials talk about the percentage of convictions and the percentage of prison sentences. But this is clearly inadequate. A 77.7 percent conviction rate and a 47.9 percent prison commitment rate just don't tell us very much about how the law is working if what is meant is how well the legislature's aim of curtailing the drug trade has been achieved.

In 1976 there were 10,838 felony drug arrests in New York City—lower than in other years—but it would be a mistake to conclude that the law is responsible. What is responsible is the police department's policy of not arresting masses of street-level dealers as it used to.

The place to look for judging the law's performance is not in the courtroom or prisons or ledger books but in the streets. After all, the goal was not to lock up drug dealers. That is a means. The goal was to stop or discourage drug dealing. On the law's own terms, it fails miserably. You will search in vain for an official who thinks the drug traffic has been diminished one iota.

"Drug trafficking is occurring on the streets of New York City without substantial enforcement of either State or Federal drug laws," stated a February 1977 report of the U.S. House Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control. "While New York has the most severe anti-narcotics laws in the nation, these laws do not act as a deterrent and have had little or no effect on traffic or use."

"It clearly has not had an impact on drug use in the city," said Cesar Perales, director of the city's Criminal Justice Coordinating Council. "I can't think of one good thing to say about the Rockefeller drug laws. You have to have the worst luck in the world to get busted."

"It seems we've had no visible impact on the problem," said Deputy Mayor Nicholas Scoppetta.

This is just a sampling of the bad marks given this law.

"TOLD YOU SO"

In looking back to 1973, one can see that most of the critics' predictions about the law have come true.

The courts, as we've seen, were badly strained until the law was amended; the prison system is now feeling the new burden of more and longer sentences; the parole department is bracing itself for the next several years, when the consequences of lifetime supervision will begin to show; children under 16 years old are reported involved in the heroin trade because they are not liable for adult sentences.

As predicted, rehabilitation programs have been drastically cut as mandatory jail terms shrink the pool of prospective "patients." (For a variety of reasons, including the coercion, the cutting of these programs may be the only beneficial effect of the law.)

And, also as predicted, the higher echelons of the drug industry appear safe from state interference. The police may say they are reaching larger-scale dealers, but so far there has been no penetration on the order of the French Connection of the early '70s.

Some prognosticators missed the mark. Conviction rates are higher in New York City than they were before the new law. Perhaps the antidrug feeling among jurors was underestimated.

Law enforcement officials tend to concede all of this, but they claim that the law has had one positive result: the harsh sentences convince arrested drug dealers to become informants. But given the widespread agreement that the drug traffic is busier than ever, the effect of the informants must be questioned.

There is more to be said on the subject of informants. "I find the whole concept of trying to make informers distasteful and contrary to American principles of jurisprudence," said Narcotics Court Judge Michael J. Dontzin. "It reminds me of Germany and Russia in the '40s when children turned in their parents."

The analogy isn't far-fetched. Defense attorney Gerald Lefcourt said that, typically, a college student accused of selling cocaine will be offered a lighter sentence if he informs for the district attorney. He proceeds to turn in his friends, Lefcourt said. Ominous stories of deception in these cases abound.

In general, critics note that the law shifted sentencing discretion from the judge, where Anglo-American jurisprudence placed it, to the district attorney and parole board. As if to regain it, so goes one theory, appellate judges have let their distaste for the law influence their rulings in, for instance, the search-and-seizure area. The courts have held that the police may not search a suspected drug purchaser if all that was seen passed to him was a glassine bag. A policeman must see the substance in the bag before he can search. Cases have been thrown out on this basis.

DRUG ECONOMICS

Why didn't a law as harsh as this one stem the drug trade? Gerald Lefcourt, who frequently defends dealers in court, provides an answer, "It's absurd to think you can stop drug traffic with a statute. You can make $75,000 for a few hours work. How can a law stop that? It's immature for people to think they can do that."

The huge profits are the product of the black market, which, as Dr. Murray Rothbard noted in an interview, results from government prohibition. The laws restrict the supply, limit distribution channels, and create risks that dealers want to be compensated for. The heavy profits, which tend to rise as the state becomes more vigilant, are gilt-edged invitations to potential dealers.

"You can kill every major drug dealer in New York," said Dr. Ernest van den Haag, a New York University social philosophy professor, "and within half a year you'll have just as many as before, probably more, because it is very profitable."

These basic economic facts debunk one of the popular myths of drug-law enforcement. Large seizures of illegal drugs, rather than helping the situation, actually worsen it. The smaller supply pushes prices up further, and users commit more crimes to meet the added expense. A 40-month Detroit study found this to be the case.

The iconoclastic psychiatrist Dr. Thomas Szasz questions the premise that the state wants to enforce the law. Calling it a "symbolic law," he said the purpose of it was not to abolish drugs, but to "fleece the public," control persons with socially unacceptable conduct, and provide huge salaries, fancy laboratories, and other "perks" and prestige to so-called drug abuseologists.

Asked if the law could be enforced if the authorities wanted to Szasz replied, "Not in a democracy. In China they do; they shoot them. But in a democracy, you need to indict the offender and give him a trial. Who's going to be on the jury? The jurors are using drugs. Who's going to sit on the bench? The judges are using them. It's a terrible con game."

By now, the public must sense this and must wonder in particular about cocaine, which, as the mass media recently discovered, is making a massive comeback in popularity. "And its popularity has yet to peak," says Newsweek. It is especially in vogue among the very affluent, making it probable that cocaine will follow marijuana along the path to decriminalization. But for now, the situation provides the ultimate irony. Men and women sit in Attica under life sentences for selling the slightest amount of cocaine, while Tiffany's is selling silver "coke straws" for $10.

It is remarkable that the drug trade seems to be largely unaffected by new campaigns, seizures, arrests, and laws. Its resilience and adaptability are, perhaps ironically, tributes to free (though hassled and distorted) enterprise. Because of its diversity—and competition among the Mafia, black crime organizations, and Hispanics, as well as independents—the illicit drug industry seems capable of fulfilling its customers' needs one way or the other regardless of the law.

A PRACTICAL SOLUTION

What does the future hold? The most drastic change could occur if an appeal argued last year in federal court is successful. Hopes that the law will be declared unconstitutional are not high, however.

That leaves the legislature as a source of change. But aside from a young, liberal assemblyman, Richard Gottfried, who was behind the marijuana changes, no one else in Albany sees this as a burning issue. Gottfried's Codes Committee is seeking to have lifetime parole abolished, and another bill would abolish the life sentence for small-scale sellers.

In New York City, law-enforcement funds are so scarce that officials are talking about experimenting with a British-style heroin maintenance program. "We can't afford to keep going like this," said Deputy Mayor Nicholas Scoppetta.

Of course, the one approach rejected out of hand is the one consistent with an individual-rights tradition—repeal of drug prohibition. It is also the approach that would best solve the problems now attendant upon drug use. Free trade in drugs would bring the black market into the open—drastically lowering crime-inducing prices, insuring marketplace quality control, making the street "pusher" obsolete, and undercutting organized crime's de facto drug monopoly.

The laws—not the drugs—are the source of the problems. Before 1914, there was no prohibition of opiates and cocaine, and there was no drug problem or "drug-related" crime. The drug problem and drug "abuse" were born the day drugs were made illegal. Thus does Szasz advise:

"It is time that we look more closely not only at what harmful drugs and profit-hungry pushers do to us, but also what harmful laws and power-hungry politicians do to us. In the history of mankind, many more people have been injured by laws than by drugs, by politicians than by pushers."

A native of Philadelphia, Sheldon Richman has been practicing journalism for more than six years and is currently a reporter in Wilmington, Delaware. This article was prepared under a grant jointly supplied by the Sabre Foundation and the Cato Institute.

What Is Addiction?

The terms "drug addiction," "drug addict," "drug abuse," and "dangerous drugs" have been avoided here—for a very simple and very important reason: contrary to general impression, it cannot be taken for granted that most people know what these terms mean. The "experts" themselves don't often agree.

The definition of drug addiction that most people obtain by osmosis is that it is a condition—even a disease—in which a person craves a drug in increasing amounts and suffers when he stops taking it. One of the key aspects of the concept is that the addict can't help himself. He gets "hooked" and then he "hooks" others. Another important aspect is that addiction is harmful to the addict and society. The World Health Organization uses this definition:

Drug addiction is a state of periodic or chronic intoxication detrimental to the individual and to society, produced by repeated consumption of a drug (natural or synthetic). Its characteristics include: (1) an overpowering desire or need (compulsion) to continue taking the drug and to obtain it by any means, (2) a tendency to increase the dosage, and (3) a psychic (psychological) and sometimes physical dependence on the effects of the drug.

In considering this definition, Dr. Thomas Szasz, psychiatrist and drug-law opponent, asked in "The Ethics of Addiction" (Harpers, April 1972):

What is an "overpowering desire" if not simply a desire by which we choose to let ourselves be overpowered? And what is a "compulsion" if not simply an unresisted inclination to do something, and keep on doing it, even though someone thinks we should not be doing it?

Szasz noted that the issue of harm makes "addiction," not a medical concept, but an ethical one. Frequently, a person's conduct is considered harmful by others but not by the person acting. "Harm" implies values and purposes—that is, ethics, not medicine.

Drug addiction and drug abuse, therefore, are moral issues disguised in the white coats of medicine.

Use of the passive voice in talking about the matter is grossly inappropriate. People don't get addicted to drugs; they addict themselves. They choose to take a drug the first time (most get sick when they do) and then they (may) choose to repeat the act. Drug addiction, because of the way it is acquired, maintained, and ended, bears no resemblance to disease. It follows, then, that there can be no treatment or cure.

"It is a fundamental characteristic of human beings that they get used to things," wrote Dr. Szasz. "However, there is no mysterious process of 'getting hooked' involved in any of this. It is simply an aspect of the universal biological propensity for learning, which is especially well-developed in man.

"The opiate habit, like the cigarette habit or the food habit, can be broken—usually without any medical assistance—provided the person wants to break it. Often he doesn't."

Why he doesn't, again, is not an issue of pharmacology.

In this connection, consider the words of an addict, quoted in Richard Ashley's book Heroin.

I mean, it seemed so obvious that you had to really WANT to get addicted. The idea some people have, that if you take one shot you're addicted, is so ridiculous. As far as I could tell, it took about two weeks of steady shooting to get to the point, not where you couldn't stop, but where you really dug it and felt a craving for it.

In short, you have to work at it to become an addict.

When this addict decided heroin was interfering with other important parts of his life, he gave it up. "Even the withdrawal was inconsequential in terms of any real physical or mental suffering," he said.

Addictive drugs—are there such things? In his classic book on drugs and the law, Ceremonial Chemistry, Dr. Szasz took up this question:

Why people habitually use such drugs…need not for the moment concern us here, other than to note that the reason cannot be said to be because the drugs are "addictive." It is the other way around: we call certain drugs "addictive" because people like to use them—just as we call ether and gasoline "flammable" because they are easily ignited. It is therefore just as absurd to search for non-addictive drugs that produce euphoria as it would be to search for nonflammable liquids that are easy to ignite.

There are studies indicating that some heroin addicts are not addicted to heroin at all, but rather to the "junkie lifestyle" and its characteristic rituals.

"Drug abuse" is another nonmedical term. To abuse is to use corruptly or improperly. It implies there can be a proper use. But in the United States, the use of any amount of heroin, cocaine, or marijuana for any purpose is considered abuse and is outlawed. Alcohol, tobacco, and caffeine, on the other hand, can be both used and abused. What is the difference?

What all this suggests is, not that we outlaw drugs we believe are dangerous, but rather that we outlaw drugs for other reasons, then call them dangerous to justify the prohibition.

The point is that the antidrug movement has obscured the issues, made them harder to face, and through this deliberate obfuscation, given an undeserved alluring mystique to the prodrug movement, an appeal it could never have achieved for itself.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Rockefeller's Draconian Drug Law."

Show Comments (1)