Proposed Colorado Rules Require Stop Signs on Marijuana Edibles

Regulations also would ban the c-word from labels.

Last year, in response to concerns about unintentional ingestion of marijuana edibles, the Colorado legislature passed H.B. 1366, which requires that any such product "be clearly identifiable, when practicable, with a standard symbol indicating that it contains marijuana and is not for consumption by children." The Department of Revenue's Marijuana Enforcement Division, which is charged with issuing regulations to achieve that goal by January 1, is still trying to figure out exactly how. Rules proposed by a state-appointed working group last week would require that packages and, when feasible, the products themselves carry a red stop-sign symbol emblazoned with the letters THC to indicate the presence of marijuana's main psychoactive ingredient. Under the proposal, liquids and other unstampable products, such as granola and mixed nuts, would be sold only in single-serving packages containing 10 milligrams of THC. Under current regulations, packages for the recreational market can contain up to 100 milligrams, or 10 servings. The working group also proposed banning the word candy from the labels of marijuana edibles.

These rules are considerably less restrictive than last year's recommendation from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment that edibles be limited to tinctures and hard candies or lozenges. The department quickly withdrew that proposal, which even Rep. Jonathan Singer (D-Longmont), the chief sponsor of H.B. 1366, thought went too far. That was true for both legal and practical reasons: Amendment 64, which legalized marijuana for recreational use and is now part of the state constitution, clearly envisioned that adults 21 or older would be able to legally buy a wide variety of cannabis products. Furthermore, edibles have proven very popular among recreational consumers, and banning them would invite the proliferation of unregulated black-market alternatives.

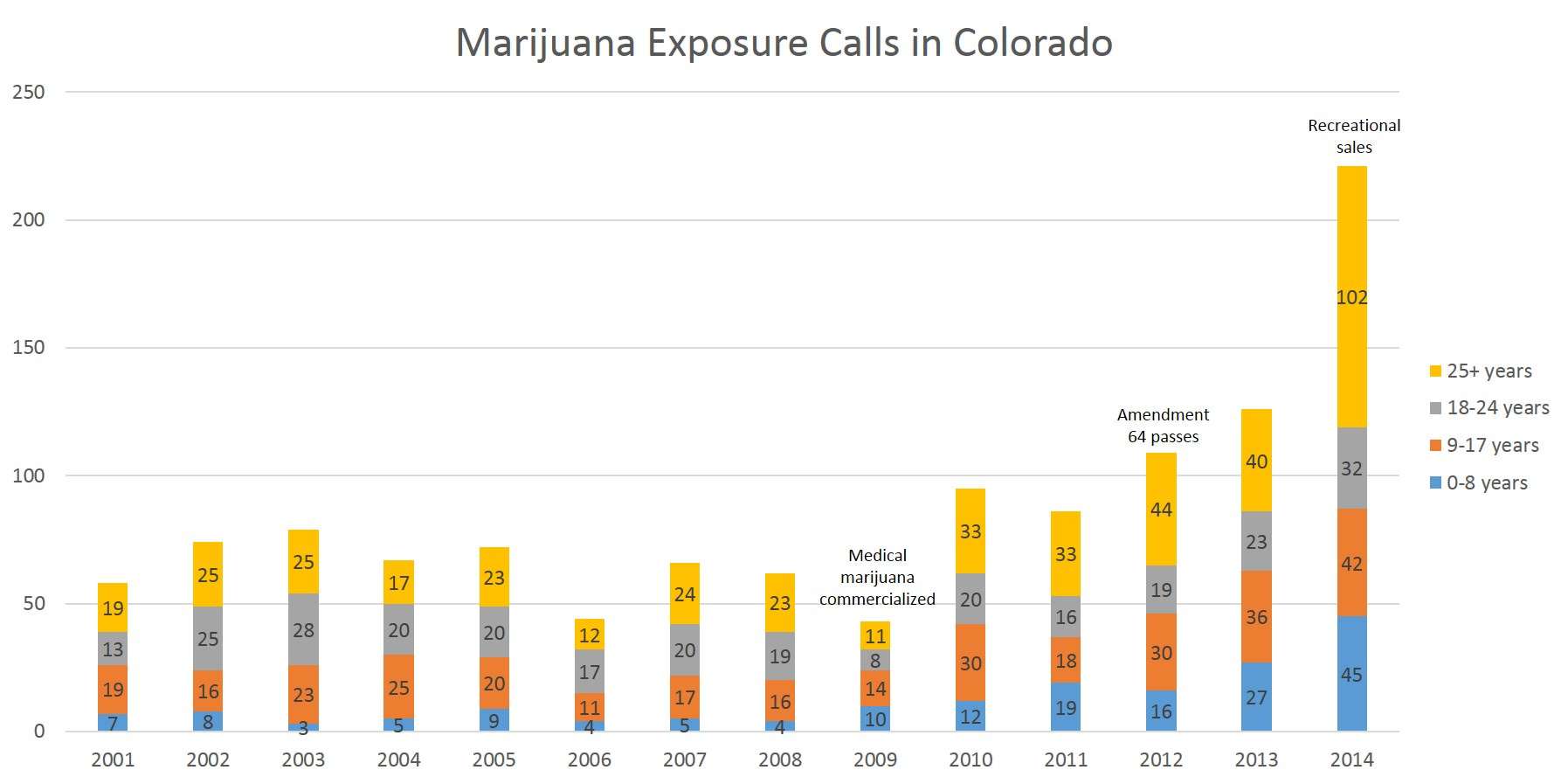

Marijuana edibles are already clearly labeled as such and sold in child-resistant packages. H.B. 1366 aims to prevent people from mistaking them for ordinary foods after they are removed from their packages. The number of "marijuana exposure" calls to the Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center rose fivefold between 2009, when the medical marijuana industry started to take off, and 2014, when legal recreational sales began. Of the 221 cases last year, 134 involved people 18 or older, and it's plausible that at least some of them accidentally ingested a marijuana edible after it was removed from its package. In those cases, a THC stop sign stamped on the product might have made a difference. It is less clear whether that symbol would deter little kids who come across unwrapped edibles. Forty-five of last year's calls involved children 8 or younger. Presumably those accidents could have been avoided by better supervision or more careful storage of cannabis comestibles.

Fortunately, the consequences of accidentally ingesting marijuana are rarely serious. Data from the Washington Poison Center, which also has seen an increase in marijuana exposure calls since legalization, indicate that just 3 percent of cases involve a "major effect." Unsurprisingly, since no fatal marijuana overdoses have ever been documented, there have been no deaths. Still, unwitting consumption of any psychoactive substance obviously can be disconcerting and unpleasant. The question is the extent to which manufacturers (and consumers, via higher prices) should bear the burden of added precautions aimed at preventing something that does not happen very often, generally does not have very serious consequences, and already can be avoided with a modicum of consumer and parental care.

Show Comments (22)