The Fine Print in Holder's New Forfeiture Policy Leaves Room for Continued Abuses

An exception for joint task forces allows evasion of state property protections.

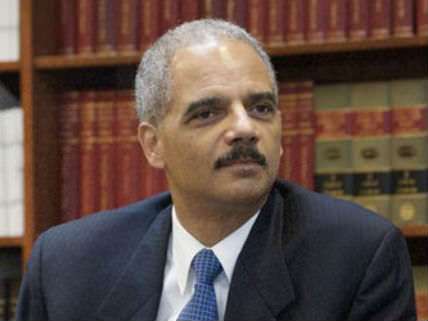

Last week Attorney General Eric Holder scaled back the Equitable Sharing Program, which enables local law enforcement agencies to evade state limits on civil asset forfeiture. But he did not end that program, and the fine print in the new policy seems to leave a lot of leeway for continued abuses.

In the order describing the new policy, Holder says "federal adoption of property seized by state or local law enforcement under state law is prohibited, except for property that directly relates to public safety concerns, including firearms, ammunition, explosives, and property associated with child pornography." Although that exception sounds like it could be a pretty big loophole, the Justice Department seems to be construing it narrowly. A newly posted form says "Federal Adoptions of state or local seizures are limited to firearms, ammunitions, explosives, and child pornography instrumentalities." In other words, drug cases do not qualify for the "public safety" exception, a point confirmed by a DOJ notice published on Friday.

A more serious problem with the new policy is that adoption, where a state or local agency seizes property and then asks the Justice Department to pursue forfeiture under federal law, is just one part of the Equitable Sharing Program. Holder's policy explicitly exempts "seizures by state and local authorities working together with federal authorities in a joint task force," "seizures by state and local authorities that are the result of joint federal-state investigations or that are coordinated with federal authorities as part of ongoing federal investigations," and "seizures pursuant to federal seizure warrants, obtained from federal courts to take custody of assets originally seized under state law."

Since there are hundreds of federally funded "multijurisdictional task forces" across the country, that first exception could prove to be very significant. Holder's order "does not prohibit the worst uses of the equitable sharing asset forfeiture program, particularly excepting seizures in which there is federal task force participation or direction," says Eapen Thampy, executive director of Americans for Forfeiture Reform. "As virtually every drug task force I know of has a federal liaison on call, this means business as usual by local law enforcement using civil asset forfeiture through the Equitable Sharing Program to enforce the Controlled Substances Act and other federal statutes. In other words, the exception swallows the rule."

On his Washington Post blog, my former Reason colleague Radley Balko highlights the same exception. "If it only applies to those investigations in which federal law enforcement personnel are actively involved," he says, "that's less troubling." Thampy is not sanguine on that point. "I do not read the Holder memo as requiring active participation," he says, "and if such a determination were to be made, it is hard to see the government defining 'active participation' narrowly." Thampy adds that "a substantial amount of equitable sharing is related to task force activity," since "most departments that receive a substantial amount of equitable sharing proceeds already do so through task force activity" that is overseen, assisted, or funded by the federal government.

The ban on forefiture adoptions in drug cases nevertheless does some good. It puts an end to egregious abuses such as the slush fund created by police in Bal Harbour, Florida, with the proceeds of federally adopted forfeitures. The Miami Herald reported that the little town's cops raked in $19.3 million over three years, which they used for parties, trips, and fancy equipment such as "a 35-foot boat powered by three Mercury outboards" and "a mobile command truck equipped with satellite and flat-screen TVs."

The Omaha World-Herald reports that Douglas County, Nebraska, Sheriff Tim Dunning is fuming about the Justice Department's new forfeiture policy. "This benefits nobody but drug dealers," Dunning said. "Federal law is a tremendously bigger hammer. I don't see what hammer we are going to have over these people now." Dunning will sorely miss that hammer, because his state requires proof beyond a reasonable doubt to seize property allegedly linked to crime, while federal law requires only "a preponderance of the evidence"—i.e., any probability greater than 50 percent.

That low standard allowed Nebraska state troopers to take $124,700 in cash from a motorist named Emiliano Gonzolez in 2003. Gonzolez claimed the money was intended to buy a refrigerated produce truck, and there was no real evidence that he was involved in drug trafficking. In 2006 a federal appeals court nevertheless upheld the forfeiture, which would not have been possible under Nebraska law. The main impact of Holder's directive will be seens in cases like this one, where a single law enforcement agency seeks federal adoption because it makes highway robbery easier or more lucrative.

Addendum: In a statement posted on Friday, the Institute for Justice expresses a concern similar to Thampy's: "Today's announced policy would stop the process of adoption, where state and local officials use federal law to forfeit property without charging owners with a crime and then profit from those forfeitures, regardless of whether those forfeitures are permitted under state law. But the new policy leaves open a significant loophole, as state and local law enforcement can still partner with federal agents through joint task forces for forfeitures not permitted under state law, and state and local law enforcement can use such task forces to claim forfeiture proceeds they would not be entitled to under state law."

Addendum II: According to a 2012 report from the Government Accountability Office, "adoptions made up about 17 percent of all equitable sharing payments" in 2010, which suggests that Holder's new policy will affect less than one-fifth of cases in which state or local agencies profit from federal forfeitures. An estimate in the press release issued by the Justice Department on Friday suggests the share is even lower when measured by revenue. "Over the last six years," the DOJ says, "adoptions accounted for roughly three percent of the value of forfeitures in the Department of Justice Asset Forfeiture Program." By comparison, the DOJ's reports to Congress indicate that equitable sharing payments to state and local agencies accounted for about 22 percent of total deposits during those six years. That suggests adoptions, which the DOJ says represented about 3 percent of deposits, accounted for less than 14 percent of equitable sharing.

Note: An earlier calculation, based on data for fiscal year 2013, put the share at less than 10 percent. The six-year average is different because of variations in total federal forfeitures and the percentage going to the states.

[World-Herald link via Notes From the Handbasket]

Show Comments (14)