That Time the President, the FBI, and a Moonlighting Supreme Court Justice Tried to Dig Up Dirt on a Movie Star

When LBJ ordered an investigation of George Hamilton.

In 1966 George Hamilton, the movie star and future proprietor of the George Hamilton Sun Care System tanning salons, started dating President Lyndon Johnson's daughter, Lynda Bird Johnson. At that point, the Philadelphia Inquirer reports,

Johnson enlisted Supreme Court Justice Abe Fortas and J. Edgar Hoover's FBI to investigate every rumor they could find about Hamilton, including claims that he was gay and a draft-dodger, in a bid to dig up dirt on the actor….Rumors cited in [the resulting file] ranged from scurrilous to outright false, including the allegation that Lynda Bird Johnson was "running around with a bunch of homosexuals," that Hamilton was a draft-dodger, and that the actor was gay and had been seen with someone described as "little more than a prostitute."

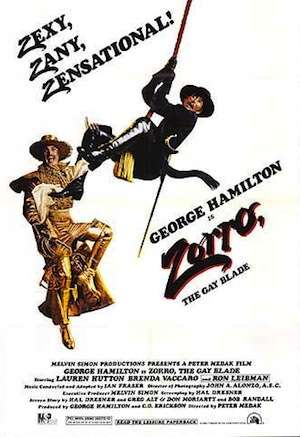

Much of this story has been told before. Catha DeLoach, the FBI man who ran the operation with Fortas, wrote about it in his 1995 memoir. And while George Hamilton's autobiography does not mention the FBI probe, it does describe the "incredible scrutiny" he faced at the time, noting that the actor's brother was gay and that "'gay' was the dirtiest word anyone could have used in and around the Johnson White House." (*)

But the bureau's full file on the investigation has yet to be released. Two years ago, Tuan Samahon, a law professor at Villanova, sued to pry the file from the government, hoping it would shed light on Abe Fortas' career on the court. Last week U.S. District Judge Eduardo Robreno issued an opinion in the case.

Robreno notes that the full file "is overflowing with gossip, rumor, and third-level hearsay concerning potentially embarrassing allegations and personal details about private citizens," and that some of this material may thus be exempt from the Freedom of Information Act. He has ordered the FBI to review its documents and release any material that does not pose these potential privacy problems. In the meantime, the judge says the bureau must produce the unredacted version of DeLoach's memorandum on the investigation—that is, a version where Hamilton's name is not blotted out.

We may never get to see every page of this story, but what we do know shows, as Robreno writes, "the ways and means of the government's investigation of private citizens in the 1960s." More specifically, it shows the particular styles of sleaze that coagulated in the Johnson White House, the Hoover FBI, and Abe Fortas' office at the Supreme Court.

(* I have not read either of those books, but both are cited in Judge Robreno's decision.)

Show Comments (60)