Obama: We Have to Do Something About Student Debt and This Is Something

Something is always better than nothing, right?

President Obama, keenly aware that he has to keep millennials on his side to prevent the Democrats from getting trounced at the polls in November, wants to confront the student loan crisis. But the current mess is itself the product of bad incentives engineered by government planning. Obama's approach won't plug the trillion–dollar debt sinkhole, and the one favored by Senate Democrats may worsen it.

Obama signed an executive order on Monday increasing the number of debtors who will be allowed to repay their federal Stafford student loans under more lenient circumstances. More borrowers can now enroll in a plan that obligates them to pay only 10 percent of their income every month as they work off their debts. After 20 years, the government writes off their debts entirely (or after just 10 years, if the borrower is working in the all-important field of public or government service).

Previously, only those who borrowed loans after 2007 were eligible for the repayment plan. It is now available to everyone.

The president also endorsed a bill sponsored by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Massachusetts), that would allow students to refinance their loans at lower interest rates. He called her proposal a "no-brainer."

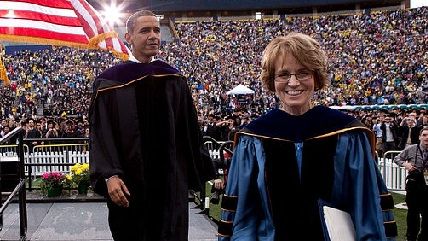

"I'm only here because this country gave me a chance through education," Obama said. "We are here today because we believe that in America, no hard-working young person should be priced out of a higher education."

That's a nice sentiment, albeit one that is completely at odds with what Warren's bill actually does. When federal lawmakers forgives debts—in part or in whole—they reward students who borrowed recklessly.

They also incentivize universities to raise tuition prices. College administrators know that they can get away with demanding more money, because students will take out more loans, confident that the government will bail them out if they run into trouble—and the government will stick the taxpayers with the bill if the students aren't able to pay.

Or, as the Cato Institute's Neal McCluskey put it:

Making student loans cheaper, which includes indicating that Washington will always soften your loan terms if politically possible, mainly encourages students to demand more stuff, and colleges to charge more. They're called "perverse incentives."

Keep in mind that public universities have shown zero interest in controlling their costs: Every year, they hire more administrators and build fancier dormitories and sports stadiums. But students will pay whatever they are asked to pay. They may never find jobs, but as long as they commit to decades of public service, their debts will eventually fall to someone everyone else.

This is what results from tackling college costs on the back end, rather than upfront. But, as seems to be the case with a chief executive who promised a "year of action" in 2014, the government just needs to look like it is doing something, even if that something is remarkably shortsighted and contributing to the very problem it intends to solve.

Something is always better than nothing, right?

Show Comments (92)