Treating PTSD with Medical Marijuana Could Curb Veteran Suicides

When T.J. Thompson returned from serving in Iraq, the Veterans Administration put him on Lorazepam, a high-potency, short-acting drug used to fight anxiety, insomnia, seizures, and aggression. It didn't work. Thompson's anxiety worsened until it almost killed him. In Thompson's own words:

I took 28 [pills] and blacked out one night. I also drank an 18 pack of beer in that same night. I declared that I would never take nor have that medication in my house again.

His brush with death is, tragically, more common than you might think. U.S. military veterans are committing suicide at increasing rates—averaging 22 per day. That's 20 percent higher than in 2007.

Prescribing powerful psychotropic (mood altering) drugs like Lorazepam for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anxiety is common practice among military doctors, but thankfully that's starting to change in response to the many negative side-effects and an almost total lack of observable positive effects.

According to Dr. Grace Jackson, a Navy psychiatrist who resigned in 2002 in protest of the "pill pushing":

Clinical studies… have shown these drugs to be no better than placebos—but far more dangerous in the treatment of PTSD.

Part of the problem with treating PTSD with high-intensity (and generally highly-addictive) pills is the tendency for veterans to self-medicate, according to Alec Dixon, a U.S. Navy veteran and the Director of Client Relations for SC Laboratories.

Veterans—whether Iraq, Afghanistan, Gulf, Korean, or Vietnam War vets—have largely self-medicated as a form of personal coping and treatment with PTSD. Often it is excessive binge consumption of alcohol alone or combined with a cocktail of other prescribed medications. Most vets and active duty military turn to alcohol from an inebriate standpoint due to the "zero-tolerance" policy on cannabis within the UCMJ and, historically, within the Veterans Administration.

But to say that the Veterans Administration (VA) is turning a blind eye to the appalling number of military suicides, however, would be unfair. To their credit, they are open to alternate ways of solving the problem. Michael Krawitz, Executive Director of Veterans for Medical Cannabis Access (VMCA) and a plaintiff in Americans for Safe Access v. Drug Enforcement Agency, admits that the VA is trying to make progress.

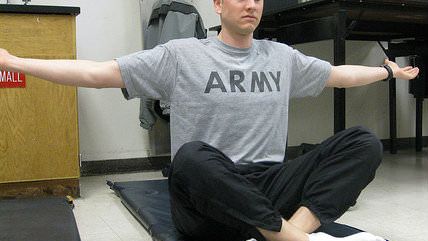

The Army and Veterans Administration are trying their best to deal with these issues and have gotten pretty creative: employing meditation, yoga, and even service dogs to assist vets dealing with PTSD. But they haven't yet discovered cannabis.

Should they? The VMCA has collected an impressive amount of studies that suggest that medical marijuana is a safer and more effective way to treat PTSD and anxiety. They submitted it to the State of Michigan Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs (MDLRA) in an attempt to convince the Michigan Medical Marijuana Review Panel that PTSD should be a qualifying condition for patients to be prescribed medical marijuana. They have also sent in similar packets to New Mexico and Oregon.

(You can download the studies in the same format as they were submitted to the MDLRA here: Packet 1, part 1 of 3, Packet 1, part 2 of 3, Packet 1, part 3 of 3, Packet 2, Packet 3.)

Thompson has already turned from Lorazepam to marijuana after his frightening experience. He says, "I can use marijuana to help with the same [anxiety] symptoms and not worry about overdosing."

Other vets are learning the same thing—but are forced to live in constant fear of arrest because marijuana is still illegal at the federal level, even in cannabis-friendly states like Colorado. Former U.S. Navy Corpsman Jeremy Usher is one such example. He had to obtain an expensive prescription for Marinol, a synthetic version of marijuana's active ingredient, THC, to manage his PTSD symptoms while on probation for three DUIs—all of which he accrued after returning from Iraq and Afghanistan in 2003. He is a poster-boy for the self-medication that is all too common among the shell-shocked vets who don't receive effective treatment.

Admittedly, asking the DoD to turn a blind eye to recreational use of marijuana in states where it has been legalized seems a bit much. It is understandable for them to assert that soldiers and defense contractors must meet certain standards of readiness.

But this outrageously outdated stance on marijuana that the military takes—which ignores the rapidly-growing amount of scientific research which shows that medical marijuana is a cheaper, safer, and more effective means to treating PTSD—hurts our veterans. It kills them.

How many could we save by switching our treatment strategy away from psychotropic drugs and towards medical marijuana? It's worth finding out.

[Disclosure: The writer is a proud member of the U.S. Army Reserve.]

Show Comments (171)