What Ken Burns' New Film Gets Right—and Wrong—About the Roosevelts

In his latest documentary, Ken Burns examines the tangled lives of Theodore, Franklin, and Eleanor Roosevelt.

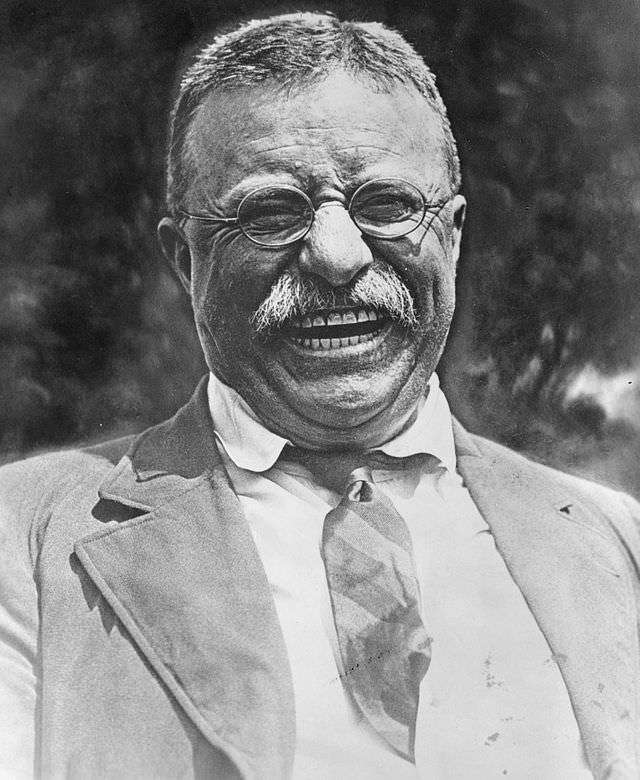

During the first half of the twentieth century, the Roosevelt family rarely strayed far from the commanding heights of American power. Theodore, the pugnacious "Rough Rider" who fought in the Spanish-American War, occupied the White House from 1901 to 1909. His fifth cousin Franklin (who was married to Theodore's niece Eleanor), took TR's strenuous example and ran with it. After serving as assistant secretary of the Navy and governor of New York, FDR would be elected to a remarkable four terms in the White House, holding office from 1933 until his death in 1945, the first and only president to break the two-term tradition established by George Washington.

Between them, Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt ushered in an unprecedented expansion of the U.S. government, erecting the foundations of the modern welfare state while at the same time launching the United States on its career as a global military superpower. Like it or not, we're living in a world they did much to create.

In his new film The Roosevelts: An Intimate History, acclaimed documentarian Ken Burns turns his lens on this fascinating and incomparable family. A sort of triple biography, the seven-part, 14-hour series, which premiers this Sunday night on PBS, follows the tangled lives of Theodore, Franklin, and Eleanor Roosevelt as they take political stage and proceed to shape—and misshape—American history.

"It was not our intention to make a puff piece," Ken Burns told me in an interview this week, "but a complicated, intertwined, integrated narrative about one hell of an American family."

He was partially successful. At its best, The Roosevelts offers a rich, historically grounded portrait of the three Roosevelts and the worlds they inhabited. What's more, unlike many such portraits, this one includes warts and all.

Theodore, for example, comes across as the egomaniacal, warmongering imperialist that he was. Franklin, meanwhile, is shown to be a devious and sometimes even deceitful politician—not to mention a philandering husband to his brilliant and long-suffering wife Eleanor, who quickly emerges as the most inspiring and admirable member of the clan.

And while the film is clearly pro-Roosevelt in its leanings, it does make room for certain contrarian views. Among The Roosevelts' stable of talking heads, for example, is none other than conservative writer George Will, who pops up from time to time to remind viewers that the family's impact was not always a benevolent one. "Building on the work of the first Roosevelt, the second Roosevelt gave us the idea, the shimmering, glittering idea of the heroic presidency. And with it the hope that complex problems would yield to charisma. This," Will declares during one episode, "sets the country up for perpetual disappointment."

But The Roosevelts is by no means a flawless film. For one thing, it sometimes fails to present an accurate picture of the family's political opponents. Indeed, the film leaves the distinct impression that only reactionaries and fringe loonies ever dissented from the New Deal.

Burns himself certainly seemed content to leave me with that impression during our interview. For instance, when I suggested that Al Smith, the Irish-Catholic Tammany Hall veteran and four-term New York governor who started out as an FDR ally and ended up as one of Roosevelt's sharpest critics, might have come to question the New Deal on principled grounds, Burns dismissed the thought. "What often happens with recent immigrant groups, having felt the sting of prejudice, as many Catholics did in the United States, and [Smith] certainly did as a presidential candidate [in 1928], he then became what he despised," Burns said. "He became that narrow-minded, xenophobic, 'real American,' if you will, that saw in Franklin Roosevelt incipient socialism. I think it is a huge everlasting discredit to Al Smith that he would have responded to Franklin Roosevelt's genius with such vituperative overreach."

Smith did attack FDR in vituperative terms. Addressing the Liberty League in January 1936, Smith savaged the New Dealers for what he saw as their betrayal of the Democratic Party. "It is all right with me if they want to disguise themselves as Norman Thomas or Karl Marx, or Lenin, or any of the rest of that bunch," Smith announced, "but what I won't stand for is to let them march under the banner of Jefferson, Jackson, or Cleveland."

But it's wrong to ignore Smith's principled arguments. A committed liberal, Smith not only championed progressive causes like the minimum wage and state support for the destitute; he was also a fierce opponent of the Eighteenth Amendment, which prohibited the sale of alcohol. And as Smith explained in 1933, the ugly lessons of prohibition taught him a thing or two about the dangers of an overreaching central government. The Eighteenth Amendment, Smith wrote, "gave functions to the Federal government which that government could not possibly discharge, and the evils which came from the attempts at enforcement were infinitely worse than those which honest reformers attempted to abolish." In the words of biographer Christopher Finan, Smith "began to believe that the danger of giving new power to the federal government outweighed any good it might do…. He was putting himself on a collision course with the New Deal."

In our interview, Burns told me that his film deals with the "central American question: What is the role of government? What can the citizen expect from their government?" That is indeed a central question, as hotly debated in our own age of foreign wars and economic uncertainties as it was in the ages of Theodore, Franklin, and Eleanor. Viewers cannot help but be struck by the similarities.

But Burns then surprised me when I asked him if his film also contained a cautionary tale about political power.

"I think these are people who utilized power. They didn't abuse it," Burns responded. Besides, he added, "almost everything is a cautionary tale. Eat too much ice cream and it will make you sick. And it's one of the most delicious things on earth."

To be sure, the Roosevelts did accomplish some good things—but they also used their considerable political powers to do some very terrible things. The family's legacy includes not just building national parks and passing public health regulations; it includes helping to launch bloody imperialist wars in Cuba and the Philippines (TR) and ordering the forced internment of thousands of innocent Japanese-Americans during World War II (FDR). Ken Burns may not see a cautionary tale about political power in the actions of this dynasty, but I suspect many of his viewers will reach a different conclusion.

The Roosevelts: An Intimate History premiers on PBS stations November 14-20.

Show Comments (174)